Are You Ready for the Metaverse?

COM faculty, alums and students are doing real work in a virtual world

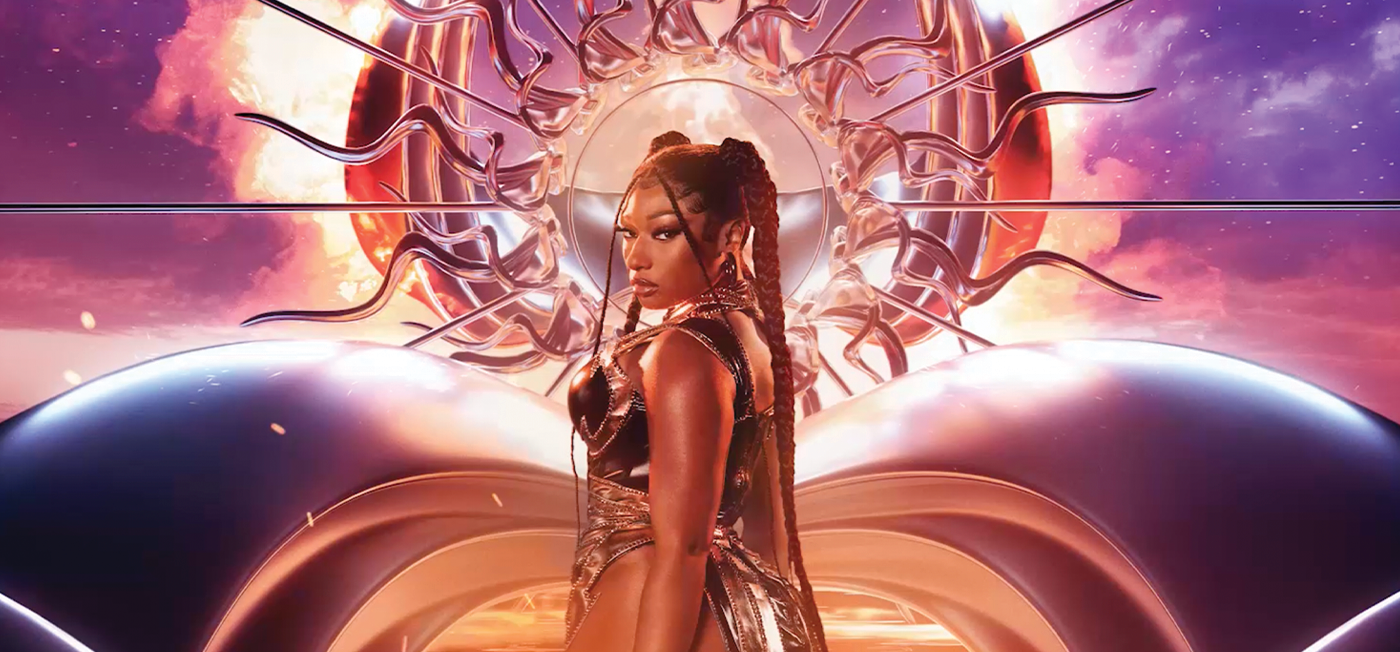

Gohree Kim ('12, Questrom'12) works at AmazeVR, a company developing tools to produce virtual concerts for artists like Megan Thee Stallion (pictured above). Image courtesy of Amaze VR

Margaret Wallace fishes an Oculus 2 headset out of a paper shopping bag. She pulls the boxy white goggles over her eyes, grabs the two controllers from her office desk and begins swiping her right hand in various patterns, trying to remember which will unlock the device. She hasn’t used it since moving back to Boston from San Francisco a few weeks ago.

Once Wallace gets into her Meta account, she hands over the headset and controllers to me. I slip it on and my eyes adjust to the depth of field as a familiar sight appears: an app menu. With a point and a click, I load a Megan Thee Stallion concert demo from AmazeVR. Suddenly I’m sailing forward over a computer-generated body of water. Wallace excuses herself and says she’ll be back in half an hour.

It feels like I’m on a roller coaster that’s gently climbing before the real ride begins. I glide into what looks like a cross between the Death Star and the USS Enterprise. A door opens to reveal a circular stage in the middle of a dark metal room. I feel the motion in my stomach and brace myself for whatever might come next, then the haptic feedback function in the controllers sends an anticipatory tingle through my hands before the lights come on and the rapper herself appears in front of me in three dimensions. She launches into her 2020 hit song “Body.”

Welcome to the metaverse, where the real and the virtual merge in spectacular fashion.

Wallace (’89) is one of COM’s newest hires, an associate professor of the practice who spent the previous three decades in the video game industry. She founded Playmatics, an interactive game studio, in 2009, and was the head of gaming technology and metaverse for the Swiss blockchain company PraSaga. At COM, Wallace will use that experience in the Media Ventures Program, where students learn how to develop their ideas into products and businesses that sit at the intersection of media and technology.

Wallace confesses that her definition of metaverse might differ from someone else’s. “There’s little consensus,” she says. “It’s continuously evolving.” To some, the metaverse is an immersive digital world where anything we do in real life will have a virtual equivalent. To others, that’s the stuff of science fiction and the metaverse will exist as isolated experiences, where the overlap of virtual and real worlds makes sense—such as in video games, online shopping or, as I’m learning, virtual concerts. Either way, demand is high for creative, digital-savvy thinkers, and Wallace is helping COM students navigate into this uncertain future.

The Metaverse’s BU Roots

Author Neal Stephenson (CAS’81) created and named the first metaverse in his cyberpunk novel Snow Crash (Bantam Books, 1992). Avatars populate virtual buildings and streets, socialize, spend digital currency and dodge computer viruses. Despite being a dystopian vision of the future, Stephenson’s novel influenced a generation of coders, gamers and tech entrepreneurs—many of whom have devoted their careers to making elements of his fiction into reality.

Thirty years later, technology is catching up to Snow Crash.

Mark Zuckerberg changed the name of his company to Meta and placed a huge bet on being able to create a virtual platform that will host the work and play of billions of people. But so far, building that virtual world has cost a lot of very real money while users and investors remain unimpressed. A recent study of Decentraland, another metaverse project, revealed that it had as few as 38 active users a day.

It’s been pretty apparent to me for a long time that things I’ve been working on in the video game industry are extending into other areas.

Margaret Wallace

As newcomers struggle to find footing in the metaverse, there is one industry that has thrived: gaming. Every day, millions of people compete, socialize and spend money in immersive video games like Fortnite. In 2020, nearly 28 million people reportedly watched an avatar of rapper Travis Scott perform a virtual Fortnite concert.

“I see how much games impact people, and it really resonates with me,” Wallace says. One of her first jobs was with P.F. Magic, which designed virtual pets. More than two decades later, she says, she still comes across fan sites raving about the product. “It’s been pretty apparent to me for a long time that things I’ve been working on in the video game industry are extending into other areas.”

The Next Internet

Jodi Luber, an associate professor of film and television and associate dean of faculty and student actions, admits she wasn’t paying attention to the metaverse until Facebook’s name change. Now, she says, she feels her students’ excitement about it. “They’re all digital natives who have grown up with the technology.”

The metaverse, says Luber (CGS’84, COM’86,’89), is “the next iteration of the internet—but what are we going to use it for and how are we going to use it?” Those are the types of questions she brings to her students in the Media Ventures Program, where the goal is to develop the plan for a startup. “You look for areas where you can innovate. What can you do that’s going to be different, or add value?”

The word “metaverse” doesn’t appear in any of the 2022 Media Ventures projects, but here are some of the ideas students came up with: virtual recording studio, remote work and collaboration platform, AI-powered fashion platform and 3D modeling and game development tools. Whether or not those students were thinking about the metaverse, they were very much focused on the future of the internet.

A current Media Ventures student, Sanjana Kumar (’21,’23), returned to COM because she considers the metaverse to be a solution to a problem she saw in her industry. Kumar, who has worked in television production and who founded Mous Films, a studio focused on sharing authentic Asian stories, was underwhelmed by the “old-school methods” she saw in pre- and postproduction. As a director, she has also struggled to explain her vision to actors and creative teams.

What if, Kumar thought, she had a virtual world-building tool where she could create a digital version of a set? Art directors would understand what she was looking for, crew members could explore and actors could rehearse in the space, and communicating across cultures and languages would be easier. Even auditions could be held in the virtual set, giving directors a sense of how an actor would interact with the world of the film. Under Wallace’s guidance, Kumar is studying the metaverse. She’s also networking at the BUild Lab in hopes of finding a partner to develop a prototype of her tool.

Technology has come a long way since Margaret Wallace wrote her thesis at COM. “I was really interested in how humans were being replaced and whether people trusted interacting with a machine,” she says. Her topic? Automated teller machines. After graduating, she headed to San Francisco. “I was really excited about the way it was possible to reach, potentially, millions of people through the internet.”

Anything we do on the internet could have a metaverse equivalent—and, after shifting our lives online during the pandemic, what don’t we do on the internet? Shopping for jeans online? Have a virtual twin of yourself try them on and see how they look. Meeting with remote colleagues? That Zoom call could be around a virtual table. Wallace expects complex trainings to occur in virtual worlds. Surgeons, for example, could practice a procedure on a digital twin of their actual patient—or guide a robot through a surgery in a remote hospital.

Two major technological hurdles remain between the internet of today and the metaverse of tomorrow: widespread adoption of headsets (Apple’s is in the works) and networks robust enough to stream extremely high definition video without any lag—so everyone sharing a virtual experience is in sync. Interoperability in the metaverse—the ability for users to seamlessly move between experiences—also remains unresolved.

Companies are already building products for that future—which brings us back to Megan Thee Stallion.

Enter Thee Metaverse

What’s remarkable about AmazeVR’s first metaverse concert is that although the setting is computer generated, it’s really Megan Thee Stallion in front of me rapping, dancing, then practically brushing my shoulder as she walks off stage. It’s a recording, not a live show—filming and streaming a live performance in 3D will require a few tech breakthroughs—but it’s a glimpse of how immersive and intense a virtual experience can be.

Gohree Kim, AmazeVR’s vice president of marketing, had explained the technology to me a few days earlier. While I viewed the concert at a resolution akin to an HDTV, that’s far smaller than the resolution of their recording—which provides a level of detail indistinguishable from reality. The company spent one day filming Megan Thee Stallion in a studio, but eight months in pre- and postproduction designing the virtual world that surrounds her—the water, the space ship, the floating bubbles that I can reach out and pop with my virtual hand. “If you don’t do it right, people will throw up,” says Kim (’12, Questrom’12), who previously worked at LiveNation and was involved in some of the first international K-pop tours.

If you don’t do it right, people will throw up.

Gohree Kim

Kim was an early graduate of the Media Ventures Program, where she studied how Microsoft could develop apps to attract customers to its Nokia phones. Now she’s drawing on that training again.

“In VR, we’re where mobile was 10 years ago—starting to build an ecosystem and building up the user experience,” she says. For AmazeVR, Megan Thee Stallion’s Enter Thee Hottieverse concert was a demo of the product they hope to eventually market. In spring 2022, the company rented out movie theaters and sold tickets to the virtual concert, providing headsets to all attendees; they’ve also launched a Meta Quest app where users can view a demo. Their ultimate hope, however, is that headsets will become widely adopted, and record labels will license the AmazeVR platform to produce virtual concerts for all of their artists.

Producing the half-hour concert was also a chance to design tools that will speed production in the future. With the use of artificial intelligence, AmazeVR hopes to cut six months of postproduction to a few weeks. This winter, they begin shooting concerts for the Korean K-pop company SM Entertainment, which has plans to launch its own metaverse studio.

The result, Kim says, won’t replace live music, but will provide fans with an entirely new experience. “You go to a live concert more for the community and the vibe. With our product, our virtual content, it’s about you and the artists. It’s about intimacy.” She recalls sharing a demo with BU Los Angeles students a few months ago. “They were screaming,” she says, as they realized they could see Megan Thee Stallion’s clothing, even nail polish, in vivid detail.

“This hasn’t been done before. We have to create a hypothesis and then be able to prove it,” Kim says. And doing so requires “the technical creative and the abstract creative—I don’t think you can be either. In the multiverse, you have to be both.”