David Huang

Read the instructor’s introduction

Read the writer’s comments and bio

Download this essay

With the advances of both the natural and social sciences, nativism and anti-immigration sentiments based on social Darwinism have largely fallen out of the mainstream culture in the United States. One would expect that Japan, a country known for its technological advances and innovation, would have also, like America, moved past using social Darwinian ideas to justify anti-immigration sentiments and policies. Yet, the post-World War II ideas of nihonjinron, a discipline dedicated to the study “of national identity and the exceptionality of the Japanese people,”1 that promotes the “idea that Japanese people are inherently, essentially, and genetically distinct” still lingers and has, in fact, been ingrained into multiple facets of Japanese society.2 Because Japanese exceptionalism and nihonjinron ideas “are still commonly accepted by Japanese people, including politicians and some academics,”3 it has allowed some nativists to argue for apartheid in Japan if immigration were allowed and to justify Japan’s anti-immigration laws on preserving the purity of the Japanese character without widespread societal objections.4 By analyzing the historical cases of anti-immigration movements in the United States circa 1890 and modern day Japan, this paper attributes Japan’s inability to overcome nihonjinron ideals to its low percentage of foreign-born inhabitants, enabling a self-perpetuating vicious cycle wherein foreigners are banned on the basis of stereotypes and misconceptions that are perpetuated by the lack of foreigners to correct these misconceptions.

While the pseudo-scientific arguments used to reinforce Japanese and American exceptionalism are termed differently—nihonjinron in Japan and social Darwinism in the United States—the underlying sentiments are the same; nativists in both countries believed that their respective populations are so far superior and advanced than other peoples that intermingling with the other so-called lesser races would dilute their greatness by contaminating their race with undesirable traits. Social Darwinism theorizes that all the races of mankind are in competition with each other and that only the fittest race can survive. Herbert Spencer’s extrapolation of the Darwinian concept of survival of the fittest into human interactions empowered nativists espousing American exceptionalism. Before the advent of social Darwinism, nativists argued that Americans were exceptional because of their republican values.5 After social Darwinism’s inception, nativists could further argue that Americans were racially superior as well, grounding their exceptionalism in biological concepts.6 Some of these nativists claimed that only the most successful Anglo-Saxons from Europe managed to reach America and, thus, America was the nation that fostered the most successful Anglo-Saxons, which the nativists already considered to be the most advanced race in the world.7 Josiah Strong, an American Protestant clergyman controversial for his advocacy of using Christianity to uplift the savage races of the world, documents the different immigrant races in his widely read book Our Country and concludes that almost every other race is inferior to American Anglo-Saxons.8 He contended that they are better-looking, stronger, and more physically fit and have taller statures, more energy, and a stronger conviction of morals. These ideas of social Darwinian American exceptionalism were pervasive, such that they were even discussed in the upper echelons of academia, managing to stay relevant for decades. Writing thirty years after Strong’s publication—a testament to the endurance of social Darwinian American exceptionalism—Edward A. Ross, a prominent American eugenist who taught at Cornell and Stanford, was one such academic who subscribed to ideas of social Darwinian American exceptionalism. Ross documented the purportedly deleterious effects of immigration in The Old World in the New, writing that Americans would lose their focus and composure if they were to “absorb excitable mercurial blood from southern Europe.”9 The idea of racial superiority and using science to justify the exclusion of other races, though, was not only limited to America at the turn of the century.

In Japan, the same sentiments of the exceptionalism and nationalistic sense of self were manifested in the form of nihonjinron, perpetuated in contemporary Japanese society through politicians and the media.10 Nihonjinron, literally translated as Japanese people theory, is a field of study that emerged after Japan’s failed attempts at imperialism in the twentieth century.11 Japan’s failure to create a pan-Asian empire forced Japanese academia and policymakers to reinvent the concept of Japanese identity from an ethno-racial hybrid to a homogenous national self-image.12 This field of study analyzes Japanese uniqueness and the reasons for their supposed superiority over other races. In the United States, social Darwinism and American exceptionalism allowed nativists to dehumanize and criminalize immigrants, portraying them as “‘unassimilable aliens,’ ‘unwelcome invasions,’ ‘undesirable,’ ‘diseased,’ [and] ‘illegal.’”13 In Japan, politicians utilize the same rhetoric against immigrant workers. The more vitriolic of these arguments come from Ishihara Shintaro, conservative former governor of Tokyo, who has publicly disparaged immigrants on several occasions. Shintaro is known for espousing nihonjinron-esque arguments, generalizing that “‘Sangokujin [third world people] and foreigners’” repeat serious crimes.14 He even posits:

Why don’t you [Japanese citizens] go to Roppongi? It’s now a foreign neighborhood. Africans—I don’t mean African-Americans—who don’t speak English are there doing who knows what. This is leading to new forms of crime. We should be letting in people who are intelligent.15

The onus of spreading and perpetuating stereotypes of foreigners is not just on the politicians; Japanese media also has a role in promoting Japanese uniqueness against the backdrop of immigrants.16 Michael Prieler, an associate professor in South Korea specializing on media representations of race and ethnicity, in his study “Othering, racial hierarchies, and identity construction in Japanese television advertising,” empirically documents that foreigners “are often stereotyped in ways that differentiate them from Japanese,” thereby “contributing… to the long-standing discourse of Japanese exceptionalism (nihonjinron).”17 Japanese actions inspired by nihonjinron—stereotyping of immigrants as well as dehumanizing and criminalizing them—is reminiscent of 1890s and early twentieth-century America and the rhetoric of social Darwinian American exceptionalism, where nativists popularized sweeping generalizations of other races.

More telling of the pervasiveness of nihonjinron ideals are the Japanese citizens’ reactions, or lack thereof, to these nativist sentiments. When Ayako Sono, a prolific conservative columnist, published her column advocating for an apartheid in Japan, the article only provoked a lukewarm response from the Japanese people and was generally met with indifference.18 Sono wrote that “all races can do business, research, and socialize with each other, but they should live separately.”19 In her article, Sono goes on to elaborate that if Japan were to increase foreign immigration, it should pursue racial segregation, unapologetically asserting that “Whites, Asians, and blacks should live separately.”20 While the international community saw the piece problematic and controversial, with the South African ambassador to Japan issuing a letter of protest, domestic Japanese media “scarcely mentioned the story.”21 The lack of widespread public outrage over Sono’s nihonjinron statements is indicative of how entrenched such ideals are in Japanese society. The relatively few objections to her article suggests that a majority of Japanese still implicitly believe in and accept nihonjinron, that the Japanese race is unique and should not risk contamination by outsiders.

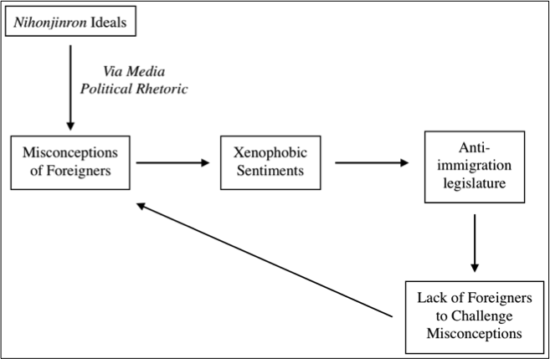

Figure 1: The Self-perpetuating Vicious Cycle of Homogeneity in Japan

Despite the fact that both social Darwinism and nihonjinron have been discredited in academia, the tenets of nihonjinron still pervade Japanese society; in the United States, it has become uncommon to base American exceptionalism on Darwinian concepts like the nativists had in the 1890s.22 The reason Japan still retains concepts of Japanese uniqueness and superiority is because of its homogenous population, wherein the foreign-born immigrants comprised of around 1.2 percent of the population in 2014 compared to America’s 14.77 percent in 1890.23 The homogenous population in Japan allows for a vicious cycle to be perpetuated (see Figure 1). The ideas of nihonjinron beget the vicious cycle by creating an in-and-out group dynamic, where the Japanese people see themselves as a unique group of people and everyone else as “agents capable of contaminating a pure ethnic Japanese identity.”24 Japanese exceptionalism, disseminated and ingrained in society through the media and political rhetoric, contributes to the misconceptions of foreigners and immigrant workers, feeding into xenophobic sentiments. These xenophobic sentiments, in turn, allow for the enactment of restrictive immigration legislation, as the Japanese people see these laws as a way of protecting their country from degradation and a form of self-preservation. The Japanese government’s stance on immigration “was and remains that of limiting the stay of migrants and assuring their return to their home countries after two or three years.”25 These restrictive immigration laws thwart the flow of immigrants and foreign populations into the country to correct the misconceptions generated from nihonjinron, further perpetuating said misconceptions. The reason social Darwinian American exceptionalism has failed to carry over into popular discourse in the twenty-first century is because the United States had a robust population of immigrants to challenge misconceptions, which prevented the formation of the vicious cycle.

In the 1890s, America shared all but one of the links of the vicious cycle of homogeneity—the lack of foreign-born residents, which effectively prevented the formation of the vicious cycle and allowed the country to cast social Darwinian American exceptionalism out of the mainstream and into the fringe discussions of immigration. As previously noted, both Japan and America had ideas of exceptionalism. Nativists were convinced that American Anglo-Saxons differed from every other race including the original European Anglo-Saxons. This generated, as nihonjinron did in Japan, misconceptions of foreigners and people of other races. The Dictionary of Races, produced as a result of the U.S. Congress’ attempt at utilizing science to craft immigration legislation, is a collection of sweeping generalizations of different races and is one such example of the misconceptions born out of the nativists’ beliefs of social Darwinian American exceptionalism.26 These misconceptions generated xenophobic sentiments, as the nativists were wary of the effects of assimilation and what that might mean for the purity of the American people.27 Fears of contamination led to anti-immigration laws such as the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) and the Geary Act (1892). However, unlike Japan, the lack of foreigners link was not present in 1890s America and, thus, disrupted the formation of the vicious cycle.

By the 1890s, foreign-born residents already comprised 14.77 percent of America’s population.28 The immigrant groups in America were able to disrupt the vicious cycle by correcting misconceptions that had arisen from social Darwinism and American exceptionalism and by participating in the political process. Prior to being elected president of the United States, Woodrow Wilson had openly championed anti-immigration rhetoric based on social Darwinism, writing in his book A History of the American People that the Southern and Eastern European immigrants had “neither skill nor energy nor any initiative of quick intelligence.”29 However, when Wilson met with delegations of immigrants on multiple occasions during his campaign for presidency in 1912, he was forced to make commitments to “the offended groups during the campaign [that] were a matter of honor with him…. That honor and commitment was decisive in his vetoes of the restrictive immigration bills in 1915, 1917, and 1921.”30 By actively participating in the political process and lobbying against restrictive immigration measures, the immigrant groups contributed to the shattering of the vicious cycle and prompted a closer investigation of the social Darwinian claims of American exceptionalism. The decline of social Darwinism is evident when scholars emerged questioning the validity of extrapolating biological phenomena observed among animals (which was where Charles Darwin documented the phenomenon of survival of the fittest) to human interactions and the social sciences.31 Now, in the twenty-first century, mainstream nativists no longer use social Darwinism to justify anti-immigration legislation. A majority of American nativists now base their anti-immigration sentiments not in racial differences and the idea of American Anglo-Saxon superiority, but rather on religious affiliation and perceived threat from certain religious groups. Because America had a large number of foreign-born residents in the country, these residents had the opportunity to band together to participate in the political process, correct misconceptions of ethnic groups, and advocate against restrictive immigration legislation—ultimately purging social Darwinian American exceptionalism from popular discourse. Conversely, Japan, owing to its low percentage of foreign-born residents, still clings to its perceived uniqueness, unwilling to let immigrants stay too long for fear of societal disruptions resulting from the immigrants’ alleged inability to assimilate.32

The historical cases of social Darwinian American exceptionalism in 1890s United States and nihonjinron in modern day Japan exhibit striking similarities in the rhetoric used by nativists in championing their own respective population’s racial superiority. What is troubling is that American nativists made these arguments over one hundred years ago. America has been able to move past using pseudo-science and racial superiority as justification for nativist and anti-immigration arguments and legislation in the mainstream. In Japan, though, nihonjinron is still being disseminated and perpetuated by politicians and the media and remains entrenched in their society. This paper contends that Japan’s low-percentage of foreign-born immigrants is the reason why a self-perpetuating cycle of homogeneity has formed in Japanese society. By looking to America’s past, this paper concludes that having a high number of foreign-born immigrants in a society is critical in breaking the vicious cycle, as they help correct the misconceptions born out of ideas of racial superiority. With a rapidly aging population, Japan can either actively pursue immigration policies that will boost the foreign-born population in the country, terminate the vicious cycle, and replenish their greying population with young immigrant workers, or they can maintain the status quo of letting immigrants stay for only a couple of years and expect their population to dwindle to around half of its current size in 2100, with the vicious cycle perpetuated ad infinitum.33 If the latter were to happen, Japan—already in its third decade of economic stagnation with its gross domestic product per capita having shrunk for the past twenty years—can expect to see a multitude of problems including: a lack of young workers to pay into the top-heavy pension schemes (it is estimated that around thirty-six percent of Japan’s population will be aged sixty-five and up) and food insecurity that threatens the extinction of “an estimated 896 Japanese cities, towns, and villages.”34 Allowing for more immigration in Japan is not just for the sake of creating a multicultural society; it is so that the Japanese can abandon embarrassing, antiquated racist sentiments of nihonjinron; it is so that they can address their demographic crisis; it is so that they can avoid enduring further economic drawbacks associated with a disproportionate aging population.

End Notes

1. Alanna Schubach,“The case for a more multicultural Japan,” AlJazeera America, November 12, 2014, http://america.aljazeera.com/opinions/2014/11/multiculturalismjapanantikoreanprotests

.html

2. Sean Richey, “The Impact of Anti-Assimilationist Beliefs on Attitudes toward Immigration,” International Studies Quarterly 54, (2010): 199.

3. Richey, “The Impact,” 199.

4. Kyla Ryan, “Japan’s Immigration Reluctance,” The Diplomat, September 15, 2015, http://thediplomat.com/2015/09/japans-immigration-reluctance/.

5. Michael W. Hughey, “Americanism and Its Discontents: Protestantism, Nativism, and Political Heresy in America,” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 5, no. 4 (1992): 539.

6. Nativists started adopting social Darwinian ideas into American exceptionalism to bolster their anti-immigration arguments between the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, where an estimated twenty-two million immigrants entered the United States between 1890 and 1930. Rachel Schneider, “The Gilded Age and the Progressive Era (1890–1900)” (video lecture, Writing and Research Seminar from Boston University, Boston, MA, October 24, 2016).

7. Josiah Strong and Austin Phelps, Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis (New York: The American Home Missionary Society, 1885), 172.

8. Strong and Phelps, Our Country, 287-96.

9. Edward Alsworth Ross, The Old World in the New: The significance of past and present immigration to the American people (New York: The Century Co., 1914), 296.

10. Richey, “The Impact,” 199; Michael Prieler, “Othering, racial hierarchies and identity construction in Japanese television and advertising,” International Journal of Cultural Studies 13, no. 5 (2010): 511.

11. Hwaji Shin, “Colonial legacy of ethno-racial inequality in Japan,” Theory and Society 39, no. 3 (2010): 328.

12. Schubach,“The case for a more multicultural Japan”; Shin, “Colonial legacy,” 328.

13. Erika Lee, At America’s Gate: Chinese Immigration During the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 22.

14. Jack Eisenberg, “From Neo-Enlightenment to Nihonjinron: The Politics of Anti-Multiculturalism in Japan and the Netherlands,” Macalester International 22, (2009): 92.

15. Ibid, 93.

16. Debito Arudou, “Tackle embedded racism before it chokes Japan,” The Japan Times, November 1, 2015, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2015/11/01/issues/tackle-embedded-racism-chokes-japan/#.WCNCT3c-JE4; Prieler, “Othering, racial hierarchies and identity construction,” 511.

17. Prieler, “Othering, racial hierarchies and identity construction,” 511.

18. Ryan, “Japan’s Immigration Reluctance.”

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. Richey, “The impact,” 199.

23. U.S. Census Bureau, Nativity of the Population and Place of Birth of the Native Population 1850 to 1990, https://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0029/tab01.html; Schubach,“The case for a more multicultural Japan.”

24. Eisenberg, “From Neo-Enlightenment to Nihonjinron,” 94.

25. Malissa B. Eaddy, “An Analysis of Japan’s Immigration Policy on Migrant Workers and Their Families” (master’s thesis, Seton Hall University, 2016), 13.

26. U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee on Immigration, Dictionary of Races or Peoples, report prepared by Daniel Folkmar and Elnora C. Folkmar, 61st Cong., 3d sess., 1911, S. Doc. 662, Government Printing Office.

27. Ross, The Old World in the New, 285.

28. U.S. Census Bureau, Nativity of the Population and Place of Birth of the Native Population 1850 to 1990.

29. Woodrow Wilson, A History of the American People (New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1902), 98–99 quoted in Don Wolfensberger, “Woodrow Wilson, Congress and Anti-Immigrant Sentiment in America An Introductory Essay” (paper presented at the Congress Project Seminar “Congress and the Immigration Dilemma: Is a Solution in Sight,” Washington, D.C., March 12, 2007), 3.

30. Ibid, 12–3.

31. Franz Boas, a German immigrant and anthropology professor at Columbia University, argued in the 1940s that “culture more than nature determined the shape of humanity and society.” Thomas C. Leonard, “Origins of the myth of social Darwinism: The ambiguous legacy of Richard Hofstadter’s Social Darwinism in American Thought,” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 71, (2009): 39.

32. Strong and Phelps, Our Country, 172.

33. Colin Moreshead, “Japan: Abe Misses Chance on Immigration Debate,” The Diplomat, March 6, 2015, http://thediplomat.com/2015/03/japan-abe-misses-chance-on-immigration-debate/; Reiji Yoshida, “Japan’s immigration policy widens as population decline forces need for foreign workers,” Japan Times, November 25, 2015, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/11/25/national/politics-diplomacy/japans-immigration-policy-rift-widens-population-decline-forces-need-foreign-workers/#.WZPN3cY7lE4

34. It is estimated that by 2030, around seventy-five percent of the farmers in Japan will be aged sixty-five and up. Arudou, “Tackle embedded racism before it chokes Japan.”

Bibliography

Arudou, Debito. “Tackle embedded racism before it chokes Japan.” The Japan Times, November 1, 2015. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2015/11/01/issues/tackle-embedded-racism-chokes-japan/#.WCNCT3c-JE4.

Eaddy, Malissa B. “An Analysis of Japan’s Immigration Policy on Migrant Workers and Their Families.” Master’s thesis, Seton Hall University, 2016.

Eisenberg, Jack. “From Neo-Enlightenment to Nihonjinron: The Politics of Anti-Multiculturalism in Japan and the Netherlands.” Macalester International 22, (2009): 77–107.

Hughey, Michael W. “Americanism and Its Discontents: Protestantism, Nativism, and Political Heresy in America.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 5, no. 4 (1992): 533–553. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20007060.

Lee, Erika. At America’s Gate: Chinese Immigration During the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Leonard, Thomas C. “Origins of the myth of social Darwinism: The ambiguous legacy of Richard Hofstadter’s Social Darwinism in American Thought.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 71, (2009): 37–51.

Moreshead, Colin. “Japan: Abe Misses Chance on Immigration Debate.” The Diplomat, March 6, 2015. http://thediplomat.com/2015/03/japan-abe-misses-chance-on-immigration-debate/.

Prieler, Michael. “Othering, racial hierarchies and identity construction in Japanese television and advertising.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 13, no. 5 (2010): 511–529.

Ross, Edward Alsworth. The Old World in the New: The significance of past and present immigration to the American people. New York: The Century Co., 1914.

Richey, Sean. “The Impact of Anti-Assimilationist Beliefs on Attitudes toward Immigration.” International Studies Quarterly 54, (2010): 197–212.

Ryan, Kyla. “Japan’s Immigration Reluctance.” The Diplomat, September 15, 2015. http://thediplomat.com/2015/09/japans-immigration-reluctance/.

Schneider, Rachel. “The Gilded Age and the Progressive Era (1890–1900).” Video Lecture for the Writing and Research Seminar from Boston University, Boston, MA, October 24, 2016.

Schubach, Alanna. “The case for a more multicultural Japan.” AlJazeera America, November 12, 2014. http://america.aljazeera.com/opinions/2014/11/multiculturalismjapanantikorean

protests.html.

Shin, Hwaji. “Colonial legacy of ethno-racial inequality in Japan.” Theory and Society 39, no. 3 (2010): 327–342.

Strong, Josiah and Austin Phelps. Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis. New York: The American Home Missionary Society, 1885.

Wolfensberger, Don. “Woodrow Wilson, Congress and Anti-Immigrant Sentiment in America An Introductory Essay.” Paper presented at the Congress Project Seminar “Congress and the Immigration Dilemma: Is a Solution in Sight,” Washington, D.C., March 12, 2007.

U.S. Census Bureau. Nativity of the Population and Place of Birth of the Native Population 1850 to 1990. https://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0029/tab01.html.

U.S. Congress. Senate. Committee on Immigration. Dictionary of Races or Peoples. 61st Cong., 3d sess., 1911. S. Doc. 662. Government Printing Office.

Yoshida, Reiji. “Japan’s immigration policy widens as population decline forces need for foreign workers.” The Japan Times, November 25, 2015. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/

11/25/national/politics-diplomacy/japans-immigration-policy-rift-widens-population-decline-forces-need-foreign-workers/#.WB_k2nc-JE4.