Vanlizza Chau

Read the instructor’s introduction

Read the writer’s comments and bio

Download this essay

Silent Anatomies

Monica Ong

Kore Press, $19.95 (paperback)

Tributary

Kevin McLellan

Barrow Street Press, $16.95 (paperback)

We find our largest source of discomfort and doubt in the machines that give us our truest identity: our bodies. As a result, our skin becomes a sealed envelope with the question: Is it wrong to be the person that I am? Wrong to love, speak, and walk without the fear of being misinterpreted or diminished? As humans, we have the natural rights to life, liberty, and property, yet minority groups and individuals are still being stripped of their ability to live full lives with the freedom to be who they are and to claim their identities without shame. Essentially, this discrimination stems from inherited conservative ideals that helped to write our nation’s blueprint into the Declaration of Independence. Thus, between the lines of “natural rights,” “liberties,” and “freedom,” many communities, including women, gay people, and people of color, were quietly excluded in the equation. Two debut poetry books, Kevin McLellan’s Tributary and Monica Ong’s Silent Anatomies, address the destructive stratifications and ongoing social inequalities that are embedded within certain traditions and cultures. McLellan and Ong both experiment with form and the figurative excavation of self and body in order to unveil the realities of being a minority. Tributary pays tribute to the voices of the LGBT community that would otherwise be muted by the echo of conservative ideals that have been passed on for generations. In contrast, Silent Anatomies articulates for the inarticulate by mapping the prevailing traditionalism of East Asian culture and its lasting mark on its people.

***

In Tributary, McLellan grapples with individual insecurity and the insecurity of the entire gay community by establishing a direct tone and control over figurative language. The reader—from the beginning—is immediately immersed in the speaker’s search for stability: “It was not that long ago / that I reached me. From where / I speak now, not exactly / whole” (5). The directness in which the speaker confronts his incomplete identity sets the candid tone for the rest of the book. Consequently, both the reader and speaker embark on a journey to translate “the foreign shapes inside [the speaker’s] blood” (7). As the book progresses, the speaker begins to define not only himself, but also the silver linings that separate certain privileges and restrictions that come from being a gay individual in society. In “The Weight of Second Person,” the speaker calls attention to the threatening routine which people easily fall victim to: “the everyday of: step, stepping, stepped” (10). This routine translates to a bigger picture; just as every individual finds comfort in a daily schedule, minority communities also easily fall into the shadows of dominating social groups that continue to dictate policy and perpetuate inequality, as the speaker states at the end of the poem: “I am sorry for us” (10). His faint apology not only addresses the gay community as a whole but also displays a small moment of self-pity.

Although the gay community has gained incredible visibility in the past decade, it is still a semi-loose collective of thoughts, bodies, and voices that seem to be “scattered in the night sky” (14). Finding the binding force that will empower such a large group begins with finding power within and accepting imperfection: “I can’t escape this / my body is a trench. / To fall in. To climb out of” (73). Essentially, the speaker must overcome his own self-doubt and find his voice before he can contribute to one louder than his. It is with this realization of inevitability that the speaker reaches resolution: “regret doesn’t exist here” (7). When the speaker recognizes his place in “this world of unidentifiables” (56) he bravely confronts his present insecurities and his past experiences in efforts to find closure in “Of Bones” (27):

(You stopped placing me

I question that which

Has always within been

Within

Atop your shoulders.)

(How can I trust

versus what is also

within? When restraint

receives a signal—

the signal—to fully surrender

what I know?)

McLellan gracefully plays with form to visually elongate the distance between present and past and how experiences from both periods of time intersect to define the person he is today. The manipulation of form is prevalent towards the end of the book where each poem after “Scattershot” becomes narrower and more minimal, ending with “Exordium” (77):

ending

becomes

last and last

becomes

salt

This simple ending imitates the crystallization of the speaker’s identity and the moment in which he finally comes to terms with the definition he creates for himself.

***

As McLellan made form an integral part in illustrating the journey towards self-realization, Ong similarly employs creative visual diagrams and graphics that take form to a whole new level. However, while McLellan’s motive is to pay a sincere tribute to the gay communities that are often misunderstood, Ong uses Silent Anatomies to criticize the negative language that surrounds women in East Asian culture. Ong underlines the goal of her collection by opening up her book with a quote from Susan Howe: “I wish I could tenderly list from the dark side of history, voices that are anonymous, slighted—inarticulate” (2).

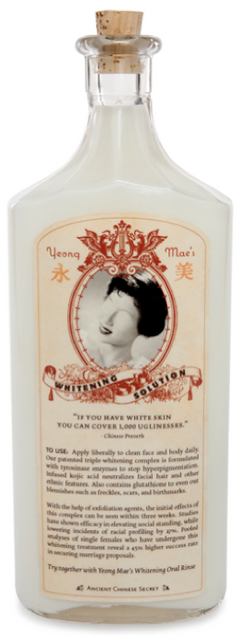

In Silent Anatomies, Ong adds satirical spice to her visual criticisms about the overpowering patriarchy in East Asian tradition. Although Ong reserves appreciation for many aspects of Asian ideology, she focuses on spotlighting the flaws within that subjugate and diminish women. In “Onset,” the series of medicine bottles serve as a satirical criticism of actual potions that impregnated mothers commonly relied on to fix the “shortage of sons” and “guarantee the protection from bearing daughters” (27) in East Asian Countries. The faces and certain body parts of the people on the medicine bottles are purposefully removed in order to emphasize an erasure and loss of identity:

The bottles pictured above and many more, such as “Perfect Baby Formula” or “Yeong Mae’s Oral Whitening Rinse,” collectively overwhelm the reader with an array of magical potions and unrealistic hopes. Effectively, the bottles’ labels call into question how ridiculously people handle such important privileges like having a child—allowing themselves to be easily tricked into taking medicines in order to prevent the “terror of asymmetry” in their offspring (27).

The angst beneath the speaker’s critique stems from personal experience. In the second poem, “Bo Suerte,” the speaker introduces a vintage family portrait in which her mother is disguised as a boy. The answer as to why lies in her mother’s explanations: “Grandfather was ashamed. / He didn’t want people shaking their heads” (5). From a young age, the speaker was already exposed to sentiments that imposed a negative connotation on being a girl: “the fact of five daughters was the immutable kind” (5). Like many other Chinese families, the speaker’s mother’s experience is something that is commonly believed to be a form of “payback” for an “unsavory ancestor in an imperial court” (5).

Ong weaves in strands of Asian superstition into her poems (“unsavory ancestor,” “Imperial court”) in order to implicitly emphasize the sometimes gullible nature of her people. Explicitly, East Asian ideologies rely heavily on old legends, superstitions, and proverbs which make their followers vulnerable to the deception of corrupt fortune tellers and medicinal doctors. Although it seems outlandish, people from East Asian countries did purchase pills like “Perfect Baby Formula” that promised “fetal masculinization” and ensured “superior academic performance” in newborns (28). Additionally, many people that fell for these fake potions and empty promises came from rural backgrounds that couldn’t afford raising daughters that wouldn’t be able to take on the family business. As a result, many people put faith in statistics and numbers that influenced whether someone chose to get an abortion or not: “the way numbers wet us with the illusion of control” (15). In “Catching a Wave,” Ong arbitrarily enters percentages on a copy of an ultrasound to highlight the deceptive nature of data and how easily numbers can be manipulated (17):

Accidents (%)

in pink plastic bags

19

on bare branches

38

fingerslipped

43

Ong’s artistic use of medical “dialect” and anatomical diagrams show how external experiences and tradition can tattoo the body with bruises of insecurity and weakness. In “Elegy,” Ong writes along an extended arm to illustrate a brief coming of age: “womanhood tore you” (37). The beginning of the arm traces to a time of liberation and liveliness: “music-spiral. night full of cars. we were girls” (37). As the poem nears the end of the hand and reaches the fingertips, lightheartedness is replaced by a “radio silent pulse” and the realization that all things come to an end: “the incompatibility of time and tumor” (37).

In “Catching a Wave,” Ong gives voice to all unborn baby girls: “she longs for a willful tide that could see her through an entire lifespan” (14). As for the women who were already born into such unfortunate social circumstances, Ong acknowledges them and the difficulty of speaking out against a tradition that other cultures may not fully understand: “If we knew all the floods that get trapped in the lungs” (45). For example, “on the Western shore,” individuals are encouraged to celebrate and embrace our bodies; however, in the East “this dialect was not designed for her” (45). The cervix and vagina are two of the most defining body parts owned by a female, yet there are no words for them in Kisoro. Rather, the area “down there” is simply referred to as a “dirty, shameful place” (45). To not only lack words to define the most crucial female body parts but also to regard them with shame are at the core of Ong’s frustration: “but what about her tongue?” the speaker asks (45). Ong leaves us with a simple question with a weighted interpretation. Essentially, we are all biologically similar—men and women both have hands, legs, and ears. So what about being a female makes our body parts less valuable?

***

Unlike Silent Anatomies, Tributary ends in a more resolute manner. The speaker finds warmth and a new beginning in the “morning light on his body” (McLellan 73). Although the speaker’s journey towards self-realization has crystallized into “salt,” a new beginning for him has emerged as he takes off on a path with his newfound radiance (McLellan 77). On the other hand, Ong concludes Silent Anatomies with a soft layer of hope while still leaving the reader looking for a passage of liberation for the speaker and girls in East Asia. Both authors artistically play with form and figurative language to excavate culture and body. McLellan and Ong similarly develop complex speakers that endure social hardship and microaggressions in order to apply their stories to the gay and feminist minority groups that are not even given the chance to be heard. Both books end on bright and comforting notes but no resolution—no call to action. It is up to the reader to articulate the issues at play and choose to make the choice to enact change or stay caged in our metal lungs. Nonetheless, both authors brilliantly construct voices for minority groups—a silent tributary to the ones that need it most.

Works Cited

McLellan, Kevin. Tributary. New York City: Barrow Street, 2015. Print.

Ong, Monica. Silent Anatomies. Tucson: Kore, 2015. Print.