Claire Rich

Read the instructor’s introduction

Read the writer’s comments and bio

Download this essay

While photography gained momentum as early as the late 19th century across the European continent, it did not become popular in Ireland for many more decades. After the 1970s, however, photography gained much-anticipated recognition and was used in the same manner as modernist paintings, as a vehicle for interpretation and a representation of conceptual thought (Carpenter 355). In his article “Photography: Representing the Present,” Ian Jeffrey claims that “time has always been photography’s particular subject” (55). In regard to time, photography can create “cruel clarity” (55) and is capable of representing the present without the softening that old painting masters could employ. This brutal, open honesty is explored and challenged in the works of Krass Clement, a forerunner in the contemporary photography movement of the time. In particular, his series “Drum” pursues “the exploration of place as a reflection of the inner psyche” (Clement). Through the analysis of Clement’s work in conversation with art historian Rune Gade, a potential deeper understanding of the images can emerge. Building on the tradition of place intimacy in the Irish mindscape, Clement’s work introduces a new twist on the contemporary photography movement as he adds the importance of place to the already established importance of time. Through this use of location in his series “Drum,” Clement is able to simultaneously challenge and encompass the tradition of contemporary Irish photography by redefining how place can be more than physical location and is capable of also capturing the inner psyche.

Ireland was slow to come around to the idea of photography’s importance. When compared to the rest of the world, the number of photographic exhibitions and galleries in Ireland devoted to photography were much, much smaller until later decades (Carpenter 355). The first photographs to gain popularity in Ireland were documents of the landscape, as “the exotic nature of Irish life attracted photographers from abroad” (357). Photographers came from both England and from the European continent to capture the mystery of the Irish landscape. This straight documentation of place was the precursor to other forms of photography in Ireland, as the early landscapes were followed by documentary projects and later, conceptual images. Artists went from documenting land and place to a “visual archive of life recorded by the communities themselves” (358). One result was the abandoning of idealistic, romantic views of the Irish landscape and the acknowledgement of sad realities like depopulation and emigration. Still depicting place, these new images drew attention to larger, more important ideas about the people within the place they were representing, marking the transition away from aesthetics to documentation.

Although the clichéd meaning of photographs is to capture a moment in time, that moment is meaningless in Clement’s series “Drum: A Place in Ireland” without the contexts of Ireland and the city of Drum. In his article, Jeffrey argues that time is what is truly captured in photographs. Claiming that “[it] has always been photography’s particular subject” (55), Jeffrey does not take into account the importance of setting and place in photographs. Clement’s work not only captures Drum at a particular time but also captures the location, which becomes essential to his series. Beginning with distant shots of Ireland as Clement travels, and continuing with almost haunting, foggy landscapes of power lines among small traditional homes in the distance, Clement sets the scene for the story he tells of this location. Clement’s trip to Drum was in 1990, but the time period is not discernable or important to the message sent through his series. The only obvious signs of modernity through these images are the presence of power lines and dim electricity in the bar, which does not accurately represent the standard of innovation present in 1990. Even the manner in which the men are dressed allows the period to remain ambiguous. The ignorance of time makes these images appear both old and new and allows the wide net of time to make the setting and location of these images infinitely more important than the period they were trying to capture. Time is an important aspect of documentary photography, but the more conceptual nature of contemporary photography does not make it an essential aspect. “Drum” is a reflection of how time can be almost completely irrelevant to a series of photographs, and how it is possible to create contemporary work without documenting a particular time. In this manner, Clement challenges the ideas of photography as he moves forward into more conceptual work that transcends time.

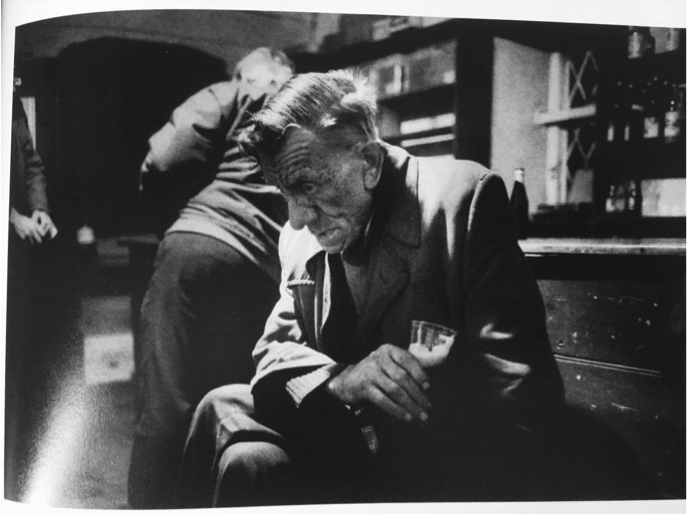

Clement’s series is a combination of extremely complex artistic decisions that retains specificity yet remains ambiguous through its title and its central figure of the old man. As Jeffrey points out, an entire premise of photography and more specifically contemporary photography is that “the medium both encourages and resists interpretation” (56). The idea of place is both specific and vague through Clement’s work, and that dichotomy is reflected in the narrow title of “Drum” and the nonspecific nature of the subtitle, “A Place in Ireland.” Through this titling, Clement leaves room for interpretation and encourages the audience to wonder what place he is truly trying to capture. Clement uses a similar approach when capturing the figure of the old man. Remaining anonymous, this figure dominates the series as he sits by himself amidst his peers drinking a tall beer. Hunched over and with a worn, deeply lined face, this man appears to be a personification of both the dingy bar and the lonely, foggy town of Drum. The man has extremely unique features with his large nose and multitude of freckles, yet despite this extremely specific documentation of the old man, the viewer may well be left wondering who he truly is and what brought him to the bar that night. The artistic decision to include a combination of specificity and ambiguity that was present in the title and subtitle combination is once again found here in the star of the series, as the old man is a similarly curious fusion of specifics and unanswered questions. Just as the viewer is left to question the story of the old man and who he is, the place referred to in the series’ subtitle remains unclear, leaving room for viewers to take away the opinions they choose.

Figure 1 – Image 51, Plate 27, Krass Clement, “Drum”

Clement’s title and use of the old man are reminiscent of the early aesthetic images coming out of Ireland in previous years; however, as Clement challenges previous generations of photography and develops documentary goals, he moves beyond mere physical capture and begins to document the emotion tied to this specific location. It is not the medium of photography that allows Clement’s work to be or not to be interpreted, but the decisions that Clement is making as an artist. As paintings or sculptures can be entirely literal or allow for more interpretations, photographs have a range of interpretative possibilities as well. It is the artist that decides to leave ambiguity and room for interpretation. Gade builds on this idea of multi-meaning by saying that the images “locate the entire suite of photographs in a symbolic and mythological space rather than a real one” (4). However, just because Clement is documenting place through the lens of the people he interacts with does not make his documentation of Drum any less real. In the manner of documentary photography, Clement aims to capture the essence of a place, and in this case, a true, specific location. In his artist statement, Clement comments on his goal to document “place as a reflection of the inner psyche” (Clement). Using the inner psyche to add an extra layer of emotional meaning and a twist of conceptual photography, Clement captures a real space, even though the characters he chooses to star in his series allow the photos to transcend place at times. While these moments showcase a more symbolic space, the series as a whole remains deeply rooted in the physical location of Ireland, which is shown through the sweeping landscapes that open his series. Through his artistic vision and decision-making, Clement expands the meaning of documentation and place as well as challenges accepted norms for the medium of photography.

While Clement’s emotions shaped his choices for the specific images he captured of this place, this place is also the necessary foundation for the development of his inner feelings of solitude and melancholy. His journey to the rainy, cold country of Ireland and decision to wander into the quaint, dingy bar that dominate his series resemble a reflection of his inner psyche. When explaining his editorial process to his graphic designer Austin Grandjean, Clement says that making this series “felt like making a kind of self-portrait, documenting my own isolation…This was February or March and it was raining all the time…It was a natural choice for me to select pictures that resonated with my own experience there” (Gade 6). Using place as a tool for expression, Clement documents not only the story of the anonymous old man and the city of Drum, but also himself. He finds shared thoughts and emotions through his choices in location and character, finding a unity within feelings of community, distance, and loneliness. Through this self-integration, Clement creates a series that is brutally honest, although, arguably, not with the “cruel clarity” Jeffrey claims photography creates (55). Through multiple layers of meaning, Clement’s series is arguably anything but clear, even though the visceral nature of the old man in particular creates a clear picture of certain aspects of Drum.

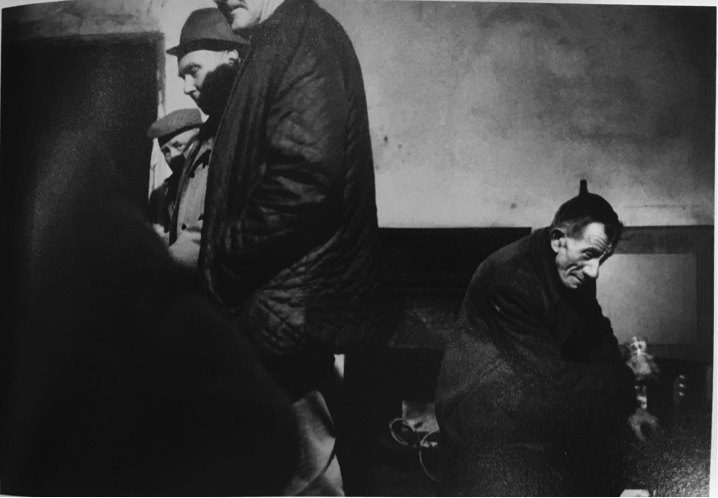

Figure 2 – Image 11, Plate 7, Krass Clement, “Drum”

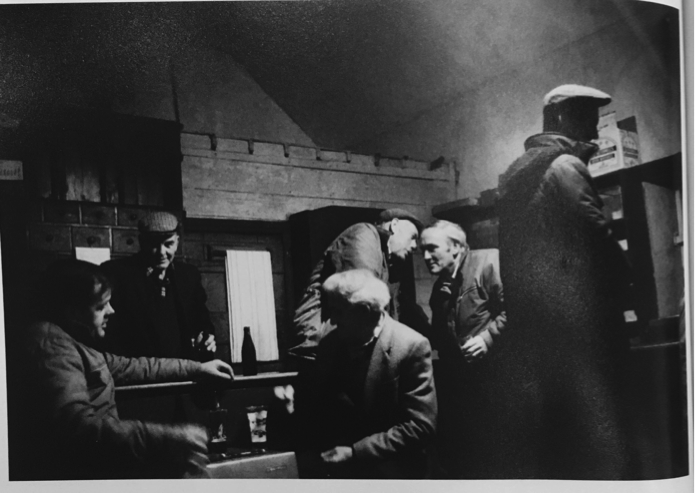

Clement’s artistic decisions intentionally cloud the meaning of his work by not only representing solitude and sadness, but also the camaraderie among groups of men. While the majority of the series resonates with the melancholy it appears Clement himself was feeling, these images are intermixed with groups of men having a seemingly good time, talking and smiling. While in ways it makes the star of the series – the sad, weathered, old man – appear even lonelier, it also creates a more complex vision of this particular place. Through this added complexity, Clement shows that places are never one dimensional, but are instead composites of multiple feelings and thoughts. Places are never simple enough to be showcased by one aspect but must be captured in more complex ways, as Clement does over the course of his series. While there is a certain dejected air about the place, there is also a particular sense of community among the members of this location.

Figure 3 – Image 35, Plate 19, Krass Clement, “Drum”

Figure 4 – Image 62, Plate 33, Krass Clement, “Drum”

Through this use of ambiguity in contrast to clarity, Clement once again challenges the purpose and definition of contemporary photography. Contemporary photography, as a whole, was centered around the idea of removing the tradition of previous generations of photographers. It was about reducing documentation and increasing conceptual thought, reducing staged portraiture and increasing the use of humanity to portray a certain emotion to send a certain message. While Clement self-defines as a documentary photographer, his inability to remain distant from his works and refusal to portray his ideas complicates that label. As he becomes more integrated and involved with the representation of both himself and the city of Drum, Clement displays the importance of place and the emotions tied to it.

Clement’s work challenges both the tradition of photography and the ever-changing concept of contemporary work. Blurring the lines between documentary photography and conceptual photography and the established purpose of these types of photography, Clement captures a unique emotional location. Place, while being interpreted literally and figuratively, almost always remains ambiguous, but its presence is essential to the intrigue that draws the viewer into Clement’s series. These strange combinations of specificity and ambiguity draw viewers into Clement’s stories, leaving us to question the story of the people and places he captures. Decades after travelling to Drum with a cheap camera and only two rolls of film, Clement’s work is still being analyzed and looked at by new generations of art historians, showing that the curiosity around these images remains. Questions about the meaning of the old man and the choice to enter this particular bar and use his rolls of film in this specific way are just some of the easy questions to ask. There are also harder questions such as what is the true meaning of place and how does one ever truly capture a location. But, just as viewers may never know the real identity of the old man, we will never have all of our questions about specific places answered, perhaps until we capture the places for themselves.

Works Cited

Carpenter, Andrew. “Twentieth Century.” Art and Architecture in Ireland, V, Royal Irish Academy, 2015, pp. 343–400.

Clement, Krass, and Austin Grandjean. Drum. Vol. 16, Errata Editions, 1996.

Gade, Rune. “Halting, Without Halting: Krass Clement’s Drum.” Drum, 1996.

Jeffrey, Ian. “Photography: Representing the Present.” Architectural Association School of Architecture, vol. 18, no. Autumn 1989, pp. 52–58. JSTOR [JSTOR].