On Climate Change, ‘the Urgency Is Great’.

On Climate Change, ‘the Urgency Is Great’

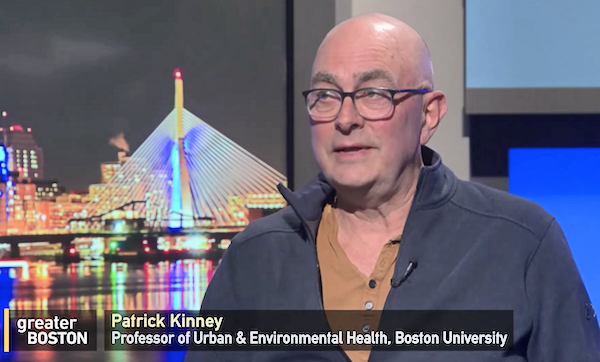

Patrick Kinney appeared on GBH’s Greater Boston to discuss the recent UN report that urges immediate global action to mitigate the effects of climate change. SPH’s Center for Climate and Health is at the forefront of these adaptation efforts to prepare communities, particularly vulnerable populations, to become resilient in the face of a rapidly changing climate.

If nations don’t take immediate action to reduce their carbon footprint, the world may suffer catastrophic and irreversible effects of climate change, according to the latest climate report by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The sixth and final cycle of the UN’s comprehensive assessment on the state of global climate crisis is still sounding alarms across the world since it was released on March 20. Climate scientists who have been warning about the long-term and inequitable effects of global warming say the need for immediate and comprehensive action cannot be overstated.

“This report really is dire and strident in its impact, and the urgency is great, said Patrick Kinney, Beverly A. Brown Professor of Urban Health and a partnering faculty member with SPH’s Center for Climate and Health, during an appearance to discuss the consequential findings on the March 22 episode of GBH’s Greater Boston. “The scientific community has been talking about this for decades, and it’s frustrating how slow the progress has been. I hope this report gets people’s attention and helps us double down on the actions that need to be done to address this problem.”

The IPCC warns that unless humans drastically reduce the use of coal, oil, and gas within the next 10 years, global temperatures will likely rise more than 1.5 degrees Celsius—surpassing the climate target in the international Paris Agreement—and cause irreversible and catastrophic damage. The powerful tornadoes, record-breaking wildfires, highly unusual snowstorms, and other severe or unusual weather events that US regions are experiencing will become even more devastating once this threshold is passed.

“During our lifetimes it’s going to get worse, but it’s going to be especially challenging for our children and their children, so what we do now will really have a huge impact on their lives,” said Kinney, who has published extensive research on the health and economic effects of air pollution, as well as the benefits of climate action plans and green infrastructure. “The report also emphasizes a really important point, which is that the people that are affected by climate change are generally the people who have been the least responsible for causing the problem. There’s an important equity issue here, as well.”

Kinney and other faculty members collaborating with the Center for Climate and Health are meeting this moment of urgency by conducting wide-ranging research to better understand, inform, and reduce the consequences of the worsening climate crisis. Since the center launched on Earth Day nearly one year ago, partnering faculty members have published papers on the physical and mental health effects of extreme heat (led by Amruta Nori-Sarma, assistant professor of environmental health, and Gregory Wellenius, professor of environmental health and director of the Center for Climate and Health); the role of greenspace on cognitive functioning (led by Marcia Pescador Jimenez, assistant professor of epidemiology); increased mortality rates (led by Kevin Lane, assistant professor of environmental health and doctoral student Paige Brochu); connections between heat and increased firearm violence (led by Jonathan Jay, assistant professor of community health sciences); and more.

Some of the latest climate-related studies by SPH researchers shed light on the inequitable burdens that vulnerable communities—including low-income residents, people of color, and children—experience as a result of climate change.

In a recent paper published in the journal Nature, Mary Willis, assistant professor of epidemiology, examined associations between oil and gas exposures and congenital anomalies in Texas between 1999–2009. She found that babies of pregnant people who were exposed to these pollutants were more likely to develop congenital anomalies, particularly cardiac and circulatory defects. In another new study, published in Environmental Health Perspectives, Willis found links between air pollution and modern-day asthma cases in neighborhoods that experienced historic redlining.

In a recent BMC Public Health study led by Chad Milando, research scientist in environmental health, and Patricia Fabian, associate professor of environmental health, several SPH researchers assessed heat adaptation interventions among Boston residents in 2020. The work was part of the first phase of the Chelsea and East Boston Heat Study (C-HEAT), a partnership that Fabian and Madeleine Scammell, associate professor of environmental health, co-direct with a goal to build capacity for the Chelsea and East Boston communities to respond to extreme heat events. Both the research team and the participants recorded information about the participants’ home temperatures, sleep patterns, location, and physical activity, and the researchers also interviewed the participants about their perceptions of heat. The study found that the temperatures that participants recorded varied widely from the ambient weather station data the team collected. The interviews provided valuable, realistic insight about heat interventions that ambient data collection overlooked—such as poorly functioning air conditioning units—and participants’ feedback revealed the need to tailor local adaptation to air conditioning use, develop public cooling services, and educate on the health impacts of extreme heat.

“It is often the communities most vulnerable to heat exposures for whom data collection is most challenging; and thus, for which tailored resilience interventions, characterized using mixed methods, can be most beneficial,” the authors wrote.

In the journal Environmental Research, SPH researchers Jonathan Levy, chair and professor of environmental health, Jonathan Buonocore, assistant professor of environmental health, and doctoral student Laura Buckley estimated the potential health benefits of the Transportation and Climate Initiative on children. The policy was a collaboration between Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states and Washington, DC that aimed to reduce carbon emissions from the transportation sector and promote sustainable communities. The team estimated that reducing carbon emissions by 25 percent from 2022 to 2032 could reduce childhood asthma, other respiratory illnesses, adverse birth outcomes, and avoid $22 million in healthcare costs.

While speaking on Greater Boston, Kinney also reiterated the benefits of public transportation, recommending that people switch from gas to electric home heating, or drive an electric vehicle, and that the city switch to all-electric vehicles.

“To take the greatest action against climate change as an individual, we need to figure out ways to reduce our own climate footprints, and that means not burning as much fossil fuels.”