Skylar Shumate

Read the instructor’s introduction

Read the writer’s comments and bio

Download this essay

There are several instances throughout the following Ted Talk script where in order to remain in the tone and style of a Ted Talk quotes or paraphrasing used to provide background information or establish functional definitions of costume elements are not book ended with the source’s information. Please refer to the corresponding footnote for information on the author and source.

Slideshow

Slide 1: Have on screen at the start of the video, but no commentary is necessary.

Slide 2: I would like to start off by having you close your eyes and visualize your favorite childhood superhero from a movie. (pause) What colors are they wearing? Do they have a cape? How about a mask? Do they have any exposed skin? Where? Can you see their face? (Pause) You can open your eyes.

Slide 3: Depending on your age, the visual and hero that came to mind may be incredibly different than that of the person beside you. Over the last forty years since the Superhero film genre first soared to new heights, superheroes and their costumes have evolved and adapted countless times. There have been color changes, technological advancements, shifts in what are considered heroic qualities and dozens of new superhumans have taken to the big screen.

The hundreds of superheroes we know today are incredibly diverse and could be talked about for hours, but I figured most of you wouldn’t like it if I kept you here past midnight, so I will focus on a specific demographic of heroes: male, human-like protagonists who I feel best exemplify the relationship between United States politics and American superhero cinema[1].

Slide 4: While these types of superheroes had been featured in comics and on a handful of TV shows prior, it was the release of Richard Donnar’s Superman – The Movie in 1978, which grossed over $134 million dollars setting it apart from any prior superhero cinema[2] – that marked the take-off of what would grow into the wildly popular, multimillion dollar Superhero film industry we know today. But how did this story about “an alien orphan…sent from his dying planet to Earth” resonate with so many and become so widely loved[3]? And why then?

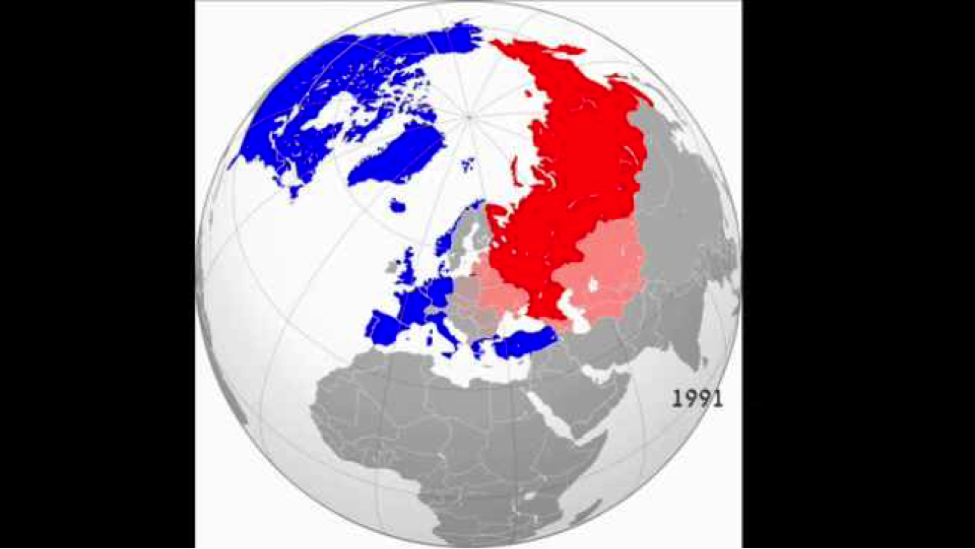

Slide 5: The 1978 release date of Superman: The Movie placed it at a turning point in the Cold War roughly halfway through the conflict[4]. Spanning from 1945 to 1991, the Cold War marked “a period of ‘non-hostile belligerency’ primarily between the USA and the USSR” immediately following World War II and continuing until the fall of the Soviet Union nearly fifty years later[5]. While no physical attacks ever occurred, these two countries with the support of their allies went head to head for the title of dominant world superpower and the right to declare their governmental style, communism versus democracy, superior. Marked not by bullets but the threat of such violence, the conflict lead to several major historical conflicts and tensions such as the Cuban Missile Crisis, Berlin Wall and Vietnam War[6]. For citizens of the United States, any communist became an enemy, space became the new frontier yet to be claimed and nuclear warfare became reality.

Slide 6: Prior to the release of Superman: The Movie, westerns had been the film genre of choice with films like Blazing Saddles (1974), True Grit (1969) and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) bringing in millions of dollars each[7]. But as the relationship between the United States and the USSR grew colder it became apparent that these horseback riding, gun slinging heroes of the Wild West were no match for the new nuclear weapons and foreign threats the country faced.

Slide 7: Superheroes like Superman on the other hand now offered a protagonist who was more than capable with the aid of superhuman strength, high speed flight and deeply rooted patriotism to fight off enemies thousands of miles away equipped with powerful nuclear weapons and corrupt morals.

Slide 8: Superman embodied the ideal American and offered audiences the success they so deeply craved after thirty-five years of political tension and the corrupt presidency of Nixon just four short years prior[8]. Craving an honest and worthy leader in the face of communism, audiences flocked to theaters to have Superman satisfy this desire. Lots of historians and researchers have explored the strong correlation between political climate and superhero cinema in regards to plot, character development and villain motives or methods as the genre has expanded and evolved[9], but the superhero costume also reveals a lot about American society at the time of the film’s release.

Slide 9: The early superheroes were catered to audiences who desired the defeat of enemies oceans away who posed a very localized threat, and their costumes reflected these political conditions. The technological advances that arose from World War II and the Nuclear Arms race that was well underway at the time made interactions between distant countries like the USA and USSR possible in ways it never had been before[10]. Conflicts like the Cuban Missile Crisis and construction of the Berlin Wall presented very localized conflicts thousands of miles from home. The nuclear arms race made an ocean of space seem insufficient to provide safety. How does one stand a chance against missiles capable of spanning hundreds of miles? Offer an equally capable opponent: superheroes.

When it comes to battling your distant yet localized enemy, it helps to have a cape to fly you there.

Throughout my research I began to identify the two primary purposes of capes in superhero cinema. The first is to enhance “the spectacle of…tremendous speed, creating the illusion of motion” and the second is to distance the hero from their “meek” alter ego[11]. The mobility that the cape provided for heroes like Superman was incredibly valuable when facing the geographically distant USSR. Meanwhile, the red cape, which is very similar to Julius Ceaser’s crimson battle cloak, marks Superman as the clear leader to be confidently stood behind as he single handedly defends and protects.

World War II was still fresh in the mind of Americans during the Cold War, and at the time of Superman: The Movie’s release the prospect of remaining comfortably at home while another who could come to no harm himself defended you was appealing to audiences. Nationalism ran strong in the blood of Americans in the face of communism. To not proudly announce your Americanism could mean you were a communist and thus an enemy.

And nothing says American like adopting the colors of our United States flag in a bright blue full body suit and a large, flowing red cape blowing in the wind much like the United States flag would.

Slide 10: Captain America and Wonder Woman would later adopt a similar United States flag- inspired look. Superman’s bold color choices make him difficult to miss, leaving pedestrians gawking in city streets, and this sense of transparency is reflective of the democratic system the United States represented in the Cold War. “While a villain may carry out his crimes in the shadows, Superman positions himself at the center of attention”. The villains of course were the communists in this narrative.

Slide 11: The eighties and nineties brought sequels, new heroes and the end of the Cold War in 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Union.

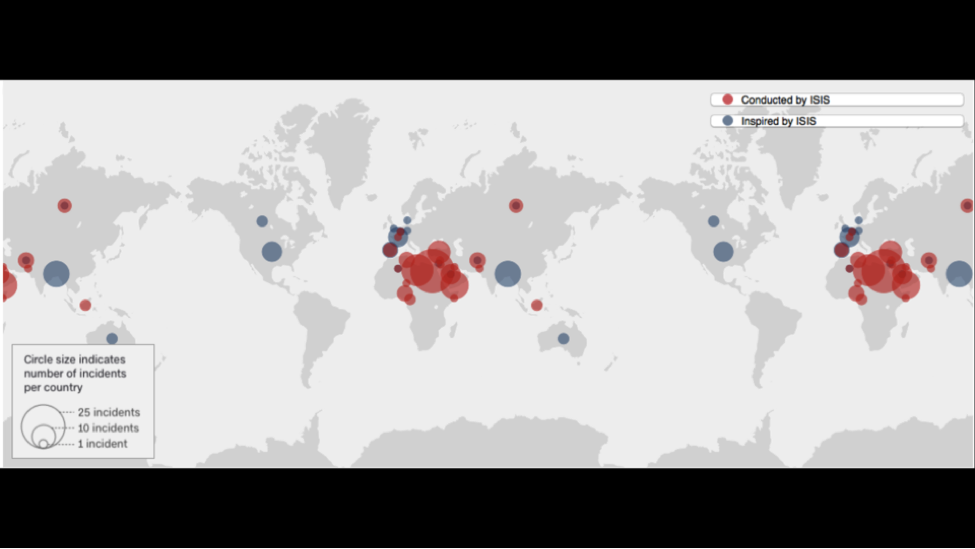

Slide 12: Then, on September eleventh 2001 the tragic attack on the World Trade Center completely altered the United States’ political climate and rewrote the definition of enemy. In his Master’s Thesis, George Briggs writes that following 9/11 the United states began “defining the enemy even more broadly than had been done during the Cold War. The war on terror was a total war that was to be fought not against a state, but against an ethos”[12]. We were no longer fighting countries easily spotted on a map, we were fighting lone rebel groups capable of spanning borders.

Slide 13: Threats to the United States have become significantly less localized in the 21st century as enemies like Isis have developed a relatively small but globally dispersed presence.

Slide 14: With no localized threat to fly to, the superhero cape has grown less relevant and began fading from superhero movies and the costumes of post 9/11 superheroes.

Slide 15: The 21st century has also brought about an exponential growth of technology and as more and more of our lives and personal information have gone digital, that too has been a target for attack. Identity protection has grown increasingly important and we no longer aim to proudly announce our personal views and values as was expected during the Cold War and instead strive to maintain some secrecy. These shifts in political ideals can also be seen affecting the 21st century, post 9/11 superhero cinema attire.

Slide 16: The bold colors previously used to announce the presence of the hero and proclaim a sense of national pride and pure Americanism have given way to darker, less pronounced color schemes that cloak the hero in secrecy and allow for more mystery as to what lies beyond the costume.

Slide 17: And the mask, whose primary purpose is identity protection, is far more prevalent as Americans have grown to value personal information even more. Cyber-attacks and increased technology have begun to remove elements of the life that were not in the public eye prior but are now available at the click of a button. Even heroes have something to lose now, their identity, and this chink in the armor has grounded them. We share the fear of lost privacy with the protectors of today and this relatability brings them down to the level of citizen making their success appear achievable. Yes, the 1978 Superman had a secret identity, but any onlooker would have made the connection. Superman was untouchable and so far above mankind that the risk of recognition was not relevant. On the other hand, modern heroes go to great lengths to make themselves unrecognizable and their existence as everyday humans empowers onlookers to see themselves as a potential hero. This concept of potential greatness is a common theme among today’s youth and can be found in nearly every college pamphlet or application essay. No wonder it has begun emerging in cinema as well.

By recognizing the correlation between politics and cinema we are able to access a new type of timeline that allows us to glimpse into the values and desires of past generations in relation to the shifting politics of the day. And moving forward, we can begin to predict the types of heroes that will appear in our future.

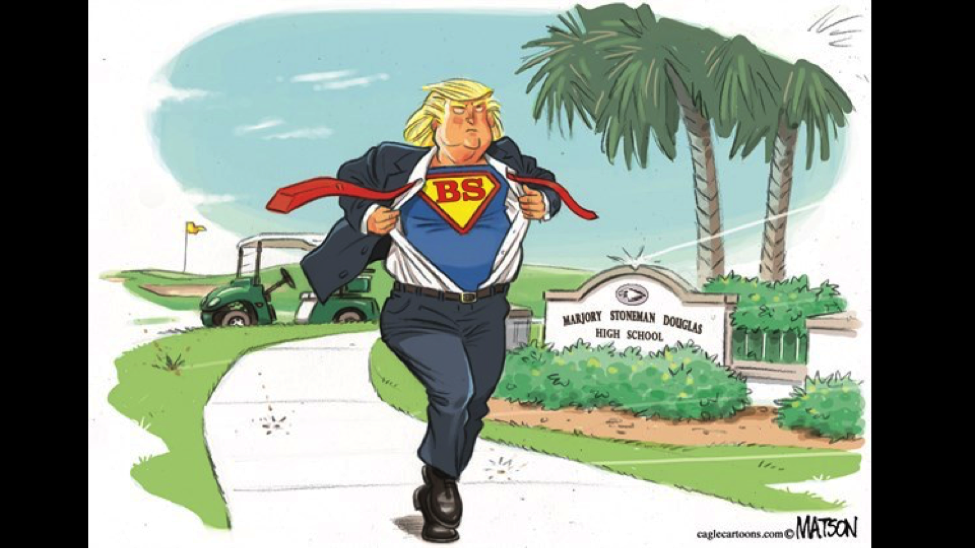

Slide 18: But what will these heroes of the future influenced by current political standings look like? I predict to see one of two options. Under the current administration, it would be unsurprising to witness a backslide to the heroes of the Cold War era. Leaders are again demanding their presence be boldly announced and perceiving themselves to be on a level higher than that of typical citizens, and as a result the red cape and bold colors may reemerge and the glimpses of humanity seen in today’s heroes may fade away. However, the second and in my opinion more likely option paints a very different picture of future heroes.

Slide 19: I predict to see a unification of heroes that rebel and push back against a common opponent

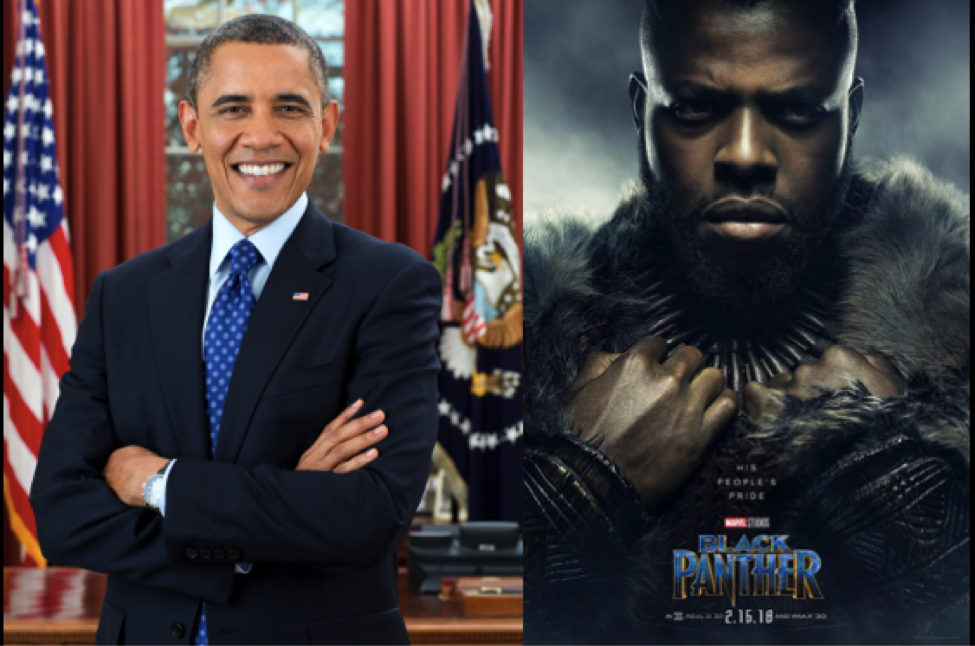

Slide 20: an increase in diversification

Slide 21: and generational inclusivity

Slide 22: And empowerment

Slide 23: and more and more glimpses figuratively and literally into the humanity of our heroes (point to tears in costume)

Slide 24: who are maybe not as different from the rest of us as we thought. Thank you.

Notes

[1] While political and cultural climate impacts all subcategories of superheroes in one way or another, my selected demographic of male, human-like protagonists best showcases my claim that a decline in capes and bright colors and increase in dark colors and masks is reflective of political turmoil the United States faced at the time of the movie’s release. For female characters, gender roles and stereotypes have a more prominent impact on costume evolution and while they are still influenced by political threats that is clouded by the gender elements also at work. I also felt the need to eliminate characters like the Hulk who do not appear human-like in their superhero form. Rather than representing the ideal man, these individuals often take the role of outsider and cannot imbody the ideal citizen in the way human-like heroes can.

[2] “Superheroes on screen 1937–2020.” IMBD. Created February 18, 2017. http://www.imdb.com/list/ls062973270/?sort=list_order,asc&st_dt=&mode=detail&page=2

[3] “Superheroes on screen 1937–2020.” IMBD. Created February 18, 2017. http://www.imdb.com/list/ls062973270/?sort=list_order,asc&st_dt=&mode=detail&page=2

[4] Because there were no physical altercations between the United States and the USSR during the Cold War, historians sometimes disagree on the exact dates of the conflict. My conclusion that 1978 fell roughly halfway through the conflict marks the start of the Cold War in 1945 when Germany and Japan were defeated in World War II and marks the end of the Cold War as the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. In the mid to late 70s, China and the United States had “established diplomatic relations” according to the timeline cited below in footnote 5 and President Nixon had recently resigned leaving the country craving an honest and trustworthy leader.

[5]Linda Alchin, “Cold War Timeline,” Dates and Events, retrieved February 2017 from http://www.datesandevents.org/events-timelines/03-cold-war-timeline.htm

[6] Linda Alchin, “Cold War Timeline,” Dates and Events, retrieved February 2017 from http://www.datesandevents.org/events-timelines/03-cold-war-timeline.htm

[7] “Most Popular Western Titles,” IMBD. Retrieved April 23, 2018 from http://www.imdb.com/list/ls062973270/?sort=list_order,asc&st_dt=&mode=detail&page=2. Blazing Saddles grossed $119.50 million, True Grit grossed $31.13 million and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly grossed $6.1 million.

[8] Linda Alchin, “Cold War Timeline,” Dates and Events, retrieved February 2017 from http://www.datesandevents.org/events-timelines/03-cold-war-timeline.htm

[9] For example, in her conference proceeding “No Capes!” Uber Fashion and How “Luck Favours the Prepared”. Constructing Contemporary Superhero Identities in American Popular Culture, Karaminas states “Superman might have been fighting communists in the Cold War of 1950s, but by the beginning of the twenty-first century he was confronting societal fears of technological doom and battling a super computer as well as taking on global fears such as the nuclear arms race and atomic testing”. Vicki Karaminas, “‘No Capes!’ Uber Fashion and How ‘Luck Favours the Prepared’. Constructing Contemporary Superhero Identities in American Popular Culture,” (In Imaginary Worlds: Image and Space International Symposium. Symposium Proceedings, Sydney: University of Technology, 2005.,) pp. 1–19.

[10] George Briggs, “From Cowboy Hats to Capes: Popular Conceptions of American Heroism,” (master’s thesis, Dartmouth College, 2011),p 13.

[11] Barbara Brownie and Danny Graydon, “Superman: Codifying the Superhero Wardrobe.” In The Superhero Costume: Identity and disguise in fact and fiction, 11–26. (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. Accessed March 11, 2018)

[12] George Briggs, “From Cowboy Hats to Capes: Popular Conceptions of American Heroism,” (master’s thesis, Dartmouth College, 2011), p19.

Bibliography

Alchin, Linda. “Cold War Timeline.” Dates and Events, retrieved February 2017 from http://www.datesandevents.org/events-timelines/03-cold-war-timeline.htm

Briggs, George. “From Cowboy Hats to Capes: Popular Conceptions of American Heroism.” Master’s thesis, Dartmouth College, 2011.

Brownie, Barbara, and Danny Graydon. “Superman: Codifying the Superhero Wardrobe.” In The Superhero Costume: Identity and disguise in fact and fiction, 11–26. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. Accessed March 11, 2018. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.bu.edu/10.5040/9781474260114.ch-001.

Karaminas, Vicki. “‘No Capes!’ Uber Fashion and How ‘Luck Favours the Prepared’. Constructing Contemporary Superhero Identities in American Popular Culture,” In Imaginary Worlds: Image and Space International Symposium. Symposium Proceedings, pp. 1–19. Sydney: University of Technology, 2005. https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/bitstream/10453/1388/3/2005001929.pdf

“Most Popular Western Titles,” IMBD. Retrieved April 23, 2018 from http://www.imdb.com/list/ls062973270/?sort=list_order,asc&st_dt=&mode=detail&page=2

“Superheroes on screen 1937–2020.” IMBD. Created February 18, 2017. http://www.imdb.com/list/ls062973270/?sort=list_order,asc&st_dt=&mode=detail&page=2.