We Have the Potential to Prevent Endemic Monkeypox.

We Have the Potential to Prevent Endemic Monkeypox

As cases continue to surge across the US, SPH professors Davidson Hamer and Lawrence Long provide insight on what we know and don’t know about this disease, as well as the best public health strategies to minimize the outbreak and dispel the stigmas around it.

The 2022 fall semester will mark the third school year of the pandemic, but this year, COVID-19 concerns will be accompanied by new caution around the rapidly spreading monkeypox virus.

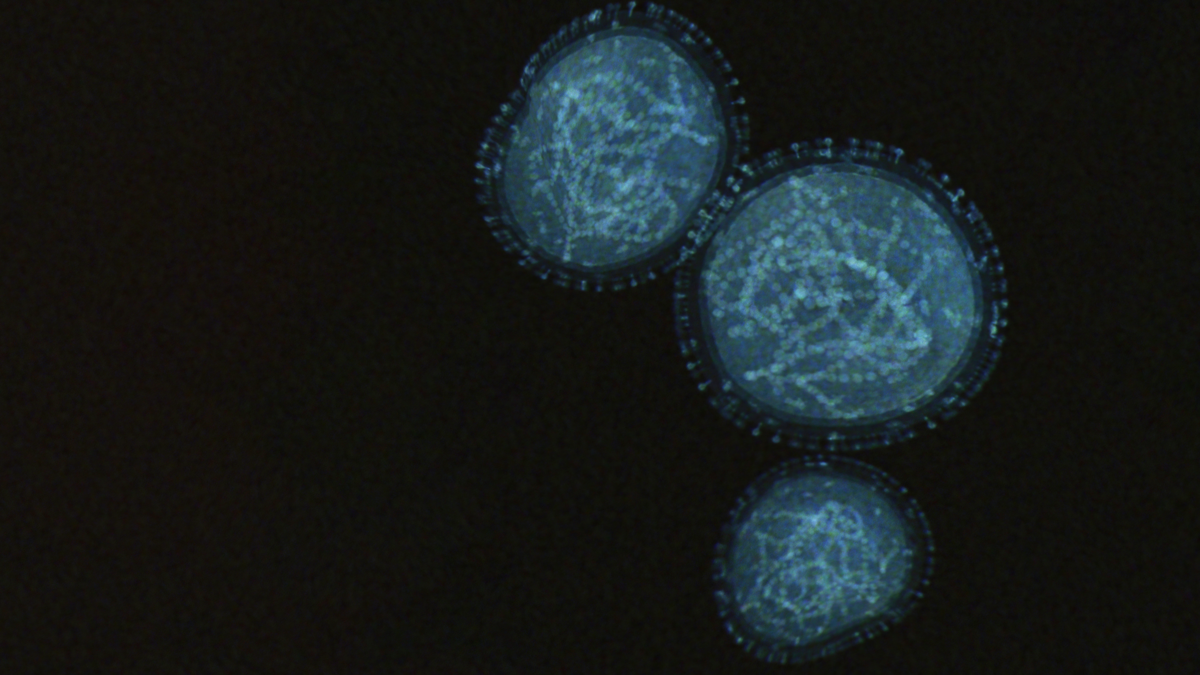

Since the first US case of the current monkeypox outbreak was detected in Massachusetts in May, confirmed cases have soared to more than 14,000 nationwide as of mid-August, reaching every state except Wyoming. Globally, countries have reported more than 35,000 cases of the rare orthopoxvirus that is related to smallpox and, until now, was largely confined to Central and West Africa.

As students return to campus, Boston University officials are working to raise awareness and educate the BU community about the rash and flu-like symptoms of the disease, as well as provide guidance and support to any students, faculty, or staff who think they may be exposed or infected.

In the United States, the unexpected outbreak has been marred by a delayed and haphazard federal response, muddled messaging, and misinformation, all of which have perpetuated stigmas and discrimination against the LGBTQIA+ community, as the vast majority of reported cases have been concentrated among men who have sex with men (MSM). Since the Biden administration declared the outbreak a public health emergency earlier this month, agencies have ramped up testing and vaccines, but access to both are still limited.

Although most cases thus far have been among MSM through sexual contact, monkeypox can infect anyone through prolonged, skin-to-skin contact and respiratory droplets. Infections have also been confirmed among the broader population, including children, as well as the first possible case of human-to-dog transmission, which is worrisome, says Davidson Hamer, professor of global health and medicine at the Schools of Public Health and Medicine, and interim director of BU’s Center for Emerging and Infectious Diseases (CEID).

“The introduction of the virus into domestic and wild animal populations, is a major concern, as it may lead to the virus becoming endemic,” Hamer says. “The very recent report of a dog who became infected with monkeypox virus shows that human-to-domestic animal transmission is possible, but not that the virus will persist and spread in domestic or wild animals. Aggressive efforts to control monkeypox now have potential to prevent the development of endemic monkeypox.”

It is critical that those efforts prioritize clear information and targeted outreach about vaccines, testing, and treatment to high-risk communities that does not reinforce stigmas or discrimination, says Lawrence Long, assistant professor of global health and a member of the Rapid Epidemiologic Study of Prevalence, Networks, and Demographics of Monkeypox Infection (RESPND-MI) reference group. “Many of the challenges we are facing now with communicating effectively about monkeypox are the same we faced with HIV, and more recently with COVID.”

On Monday, August 29, SPH will examine effective public health responses that stop the spread of monkeypox and stigmas in the virtual Public Health Conversation, “Monkeypox: Old Disease, New Fears,” cohosted by CEID and BU’s LGBTQIA+ Center for Faculty & Staff. The event will feature several guest speakers, including Hamer; Angela Rasmussen, research scientist at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization; Kellan Baker, executive director and chief learning officer of the Whitman-Walker Institute; Sean Cahill, director of health policy research at The Fenway Institute and adjunct associate professor of global health at SPH; and Elle Lett, postdoctoral fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital; and it will be moderated by Craig Andrade (SPH’06,’11), associate dean for practice, associate professor of the practice in the Department of Community Health Sciences, and director of the Activist Lab at SPH.

“The steady transmission of monkeypox and slow, uncoordinated response amid prominent warnings echo the devastating histories and stigma-fueled politics of tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, the Crack epidemic and COVID-19. The result—those most marginalized are left behind, too often with lethal consequences,” says Andrade. “The vital question is, what have we learned and not learned from the past that can point to a better, more humane way forward, for monkeypox and beyond? I’ve cared for so many across these health crises as a nurse at Boston Medical Center and I’m eager to delve deeper into this discussion.”

As we continue to learn more each day about this outbreak, Hamer and Long shed light on what we currently know about monkeypox transmission, vaccines, and treatments, and how the public health community can provide effective knowledge and leadership to protect vulnerable groups and prevent this disease from becoming a permanent fixture within the US population.

Q&A

with Davidson Hamer and Lawrence Long

What do we know—and not know—about the modes of monkeypox transmission and the group/s that are most impacted at this time?

HAMER: Past studies have suggested that monkeypox virus can be transmitted from person to person by close, skin-to-skin contact (direct contact with monkeypox rash lesions, scabs, or body fluids), and respiratory droplets. In addition, contact with infected rodents can lead to infection, like the prairie dog outbreak in 2003. There are studies showing the presence of monkeypox DNA on surfaces and that, under the right conditions, it can be present for hours to days.

However, as yet, there is no evidence that contaminated surfaces are responsible for transmission in the current outbreak in non-endemic areas. We do not know whether asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic transmission can occur although there is one study published as a preprint that suggests that this might be possible. Wastewater testing is being evaluated as a strategy for monkeypox surveillance. This looks promising.

Were you surprised by the slow federal response, given what we should have learned from COVID-19? Now that the Biden administration has declared monkeypox a national public health emergency, how can federal, state, and local officials develop a coordinated response?

LONG: I was surprised at the pace of the national response. I had expected that our recent and continuing experience with COVID would have primed the country for rapid response. In addition, the US had in theory prepared for this type of outbreak in order to counter a bioterrorism attack and so, unlike with the COVID epidemic, we had a number of effective biomedical counter measures available to us immediately such as testing, vaccinations, and treatment. Despite early calls from affected communities and activists for a rapid response to the outbreak, the delayed response has resulted in continued spread, the need for vaccine outstripping supply and the possibility that monkeypox may become commonplace in the US. My hope is that with the announcement of a national public health emergency, resources that are needed at the state and local level will continue to be released to ease the significant burden that is being placed on public health infrastructure, healthcare providers and affected communities. At the moment though, reports suggest that many of these burdens continue.

In addition to this, it will be important that the response starts addressing the significant barriers that affected communities and health care providers are experiencing in accessing rapid testing, vaccination, and treatment which extends beyond supply of commodities to the dearth of services outside of urban hubs, costs associated with accessing services, administrative burden in accessing treatment, and client and provider education on monkeypox management especially in light of the intradermal vaccination administration strategy.

Finally, we need national data on the outbreak that covers at a minimum who is accessing testing, vaccination and treatment with breakdowns by race, ethnicity, gender identity, and sexual orientation. An effective response cannot take place without this and the little data that exist suggest that to date the response has not necessarily reached those most at need nor has it been equitable. There are still many unknowns with regards to monkeypox and without strong data systems we will struggle to limit the spread of this outbreak or prevent future outbreaks.

Do you think there will be a substantial increase in cases once students return to school?

HAMER: There is a potential risk for an increase in cases in sexually active, university or college students this fall. Most universities, including BU, are developing plans to educate their students about the risk, make them aware of the need to be evaluated if they have a definite exposure or develop compatible symptoms, and to increase the availability of testing for those with possible monkeypox.

Which populations are prioritized currently for testing and vaccination, and which additional groups should become eligible next as the vaccine stock increases?

HAMER: The CDC is currently recommending post-exposure vaccination for individuals with sexual contact with anyone known to be infected with monkeypox. Ideally, this should be done within 4 days of exposure although it can be administered up to 14 days after exposure as this may help reduce the severity of infection. Lab workers who work with the virus and health care workers with significant exposures should be given the vaccine (pre-exposure). Some countries are using the vaccine (mainly the non-replicating Jynneos vaccine) for pre-exposure prophylaxis in high-risk populations (MSM, bisexual) and, in the US, some states are also approving the vaccine for use before exposure as opposed to afterwards. I am not aware of recommendations for groups such as hospitality workers, spa workers, daycare, teachers, etc. The challenge is the limited availability of this vaccine.

How effective is the Jynneos vaccine? Can you explain the “dose-sparing” approach that the FDA authorized, and do you think this is a safe and effective solution while there is a vaccine shortage?

HAMER: Dose sparing is a strategy whereby a smaller dose of a vaccine, where fractional doses of a vaccine are used (e.g. dividing one usual dose into 5 or even 10 separate doses) is used to eke out the supply of a vaccine. This strategy was used successfully with the yellow fever vaccine during large yellow fever outbreaks in Africa. The FDA approved a plan to do split dosing of the Jynneos vaccine changing from the current subcutaneous route to intradermal. This will allow five doses from each vial rather than one. The immunogenicity (how well the vaccine induces a protective immune response) of the fractional dose approach has been assessed for this vaccine in one study in 2015. The lower dose, when provided by the intradermal route, was equally immunogenic but was also associated with greater local and systemic side effects than the full dose when administered by the standard, subcutaneous route. This approach may not work well in immunocompromised patients such as those with poorly controlled HIV infection.

At this point, we need more studies to be done to quickly assess the immunogenicity of fractional doses in healthy adults, as well as those with underlying HIV infection. The animal data, especially in non-human primates, suggest that the Jynneos vaccine can prevent complications of monkeypox and even all symptomatic infections but we need prospective, carefully collected data from human populations to have greater insight into this protective aspect of the vaccine. At present, we have limited data on the duration of protection of the vaccine and the optimal timing of boosters.

Although there is no designated treatment for monkeypox, what types of care are being provided to patients?

HAMER: Monkeypox is largely managed with supportive treatment. Pain control is important since some of the lesions, especially if present on genitalia and the peri-anal region, can be very painful. Beside pain control, good basic wound care is important to prevent secondary infections. It is also important to isolate the individual, if possible, to prevent spread of the virus to family members or other sexual contacts. There is a drug called tecoviramat (TPOXX) that was developed for treatment of smallpox that is available through an expanded access protocol from the CDC for treatment of monkeypox. However, there are limited safety and efficacy data for this drug in humans.

How do we strike a balance between providing important education and outreach to high-risk populations without perpetuating stigmas and discrimination against the LGBTQ+ community?

LONG: As a starting point, it is important to communicate clearly to all how MPX is transmitted. This gives individuals, irrespective of how they identify, the necessary information to determine their own risk and take any necessary actions to mitigate risk.

We have good evidence from the HIV pandemic about how associating a disease with a particular group creates stigma and ultimately hampers an effective response. More recently, Drs. Boghuma Titanji and Keletso Makaofane have described this same issue with respect to monkeypox. The distribution of infectious diseases, including monkeypox, within the US and globally, highlights historical and current inequities in access to healthcare across geography, race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation and income. Our response to monkeypox should work to reduce this by making sure that all individuals at increased risk for monkeypox have easy access to affordable screening, vaccination and treatment if needed.

As is often the case, data is limited and so there is a need for rapid data collection and analysis to help inform an evidence-based response. A great example of this is the RESPND-MI project, run by Drs. Makofane and James Krellenstein, which aims to survey the queer and trans community affected by monkeypox in NYC to better understand community transmission. I am excited to be a member of their reference group. As an academic research community, it is our role to help build the evidence base for an effective public health response.

The average length of isolation for people who contract monkeypox is 2-4 weeks—are you worried that this extensive isolation period may significantly disrupt daily life if cases continue to rise?

LONG: The recovery time and isolation period is long. Aside from the pain associated with monkeypox itself the extended isolation is likely to place an additional mental and financial burden on individuals. The response to the current outbreak should include support for individuals during this period to address or mitigate these additional burdens.

HAMER: I agree with Lawrence’s input. The psychological and financial burden may prove to be substantial for infected individuals. If isolation is required for anyone who is a student, then we need to develop strategies, such as remote virtual learning, to help prevent a negative impact on their education.

Emerging infectious diseases have been on the rise for decades, but it seems as if we are seeing a particular spike in new or previously contained diseases, from COVID-19 and monkeypox, to polio and the new langya virus. Is this activity unusual, or a sign of improvement in disease surveillance?

HAMER: The world is changing and many different factors including climate change, environmental damage, changes in land use, consumption of exotic foods, urbanization, population growth, ease of global travel, war, and displacement of populations all influence the risk of emergence of novel pathogens. We also have strengthened surveillance systems in many parts of the world such that we are better able to identify outbreaks of novel pathogens or a resurgence in old problems like polio although we need to continue to strengthen infectious disease surveillance systems in many low- and middle-income countries.