6 New Year’s Resolutions to Improve the Health of the Public in 2017.

Happy New Year. I hope everyone has had a restful holiday season. This Dean’s Note comes on January 1, a day when we traditionally make resolutions for how to do and be better in the coming year. These resolutions often concern health. Consider, for example, the recent lifehack.com list, “50 New Year’s Resolution Ideas and How to Achieve Each of Them.” Eleven items on the list are linked with lifestyle behaviors, like getting in shape, eating healthy, and getting more sleep. As I have written before, our focus on lifestyle is a bit of a red herring, distracting us from the core social, economic, and environmental conditions that shape our health. This perhaps explains why the seasonal tide of resolutions does little to improve our collective health and well-being. So I suggest that this season we as a country collectively adopt different resolutions, resolutions about what we may do together to truly improve the health of all.

Happy New Year. I hope everyone has had a restful holiday season. This Dean’s Note comes on January 1, a day when we traditionally make resolutions for how to do and be better in the coming year. These resolutions often concern health. Consider, for example, the recent lifehack.com list, “50 New Year’s Resolution Ideas and How to Achieve Each of Them.” Eleven items on the list are linked with lifestyle behaviors, like getting in shape, eating healthy, and getting more sleep. As I have written before, our focus on lifestyle is a bit of a red herring, distracting us from the core social, economic, and environmental conditions that shape our health. This perhaps explains why the seasonal tide of resolutions does little to improve our collective health and well-being. So I suggest that this season we as a country collectively adopt different resolutions, resolutions about what we may do together to truly improve the health of all.

1. Narrow income and wealth gaps.

It is not difficult to see how the lack of money, or, worse, the accumulation of debt, can undermine health. Income determines the quality of our diet and our neighborhood, the level of education we can afford to access, and our opportunities for economic and social advancement. Any one of these factors can affect health in profound ways. A low-resource neighborhood, for example, can mean more stress, more pollution, and poorer quality food. Unfortunately, as a country we have been witness to growing income inequality, with those who have less income and wealth falling further behind. For example, the Congressional Budget Office reported that, in 2013, 76 percent of all family wealth was held by families in the top 10 percent of the wealth distribution. This calls for a resolution to invest in efforts that improve incomes for those in the lower 50th percentile. There are many ways we can do this. We could, for example, extend coverage of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), a cash-transfer benefit for the working poor that ranges from approximately $500 to $6,200, depending on income and family size. This would do much to assist low-income families. There is also the option of progressive taxation efforts such as an updated estate tax, one that minimizes loopholes, ensuring that all pay their fair share. Such a step would mitigate the concentration of wealth at the very top of the income ladder while providing funds for projects that benefit the public good.

2. Promote gender equity, both in the United States and abroad.

I have written before about how falling short on gender equity is a threat to the health of populations. In many countries, including the US, education and employment opportunities are unequally distributed between women and men, with women often at a disadvantage. Education, employment, and income are fundamental causes of health. When women are denied equal access to these assets, they are also denied access to the resources that education and income can bring, such as power, social connections, and political agency. Women also face a host of threats to their reproductive health. In this country, these include policy challenges to their right to abortions and safe reproductive care. Globally, they include challenges like the problem of female genital mutilation and the cultural enforcement of rules governing marriage and childbearing. A resolution to level the gender playing field stands to improve the lives not just of women, but of men, too. Gender inequity has intergenerational effects that shape the lives of families; indeed, whole communities.

3. Narrow social divides.

Income/wealth gaps and gender equity are both key components of the broader challenge of social divides that undermine the health of populations. These divides are a central concern of public health. Critically, these divides create barriers to the economic, social, and political resources that promote health. Race, for example, is a key marker of social divides. In the US, black–white health disparities persist for a range of health challenges. Obesity is a case in point. Between 1976 and 2004, black women had a consistently higher rate of obesity than white women (Figure 1).

Created from table 74 of National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2007 With Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans. Hyattsville, MD; 2007.

Or consider the challenge of HIV/AIDS. After many difficult years of advocacy and struggle, we can now mitigate HIV through the use of several highly effective measures, from condoms to Tenofovir disoproxil/emtricitabine (Truvada). The UN has set 2030 as a target date for “the end of AIDS.” However, this may prove unrealistic, given, among other factors, the challenge social divides pose to effective prevention. In the case of HIV/AIDS, these challenges can manifest as stigma, as well as, in some cultures, a power imbalance between men and women, which can put women at greater risk. The existence of these social divides, even within contexts where overall health is improving, speaks directly to our core aspiration of balancing “overall improvement of population health with the achievement of health across groups and the narrowing of health gaps.” A resolution to tackle social divides wherever they manifest speaks to our core concern for social justice and the health of marginalized populations, and should be an ineluctable part of our mission in public health.

4. Improve education at all levels.

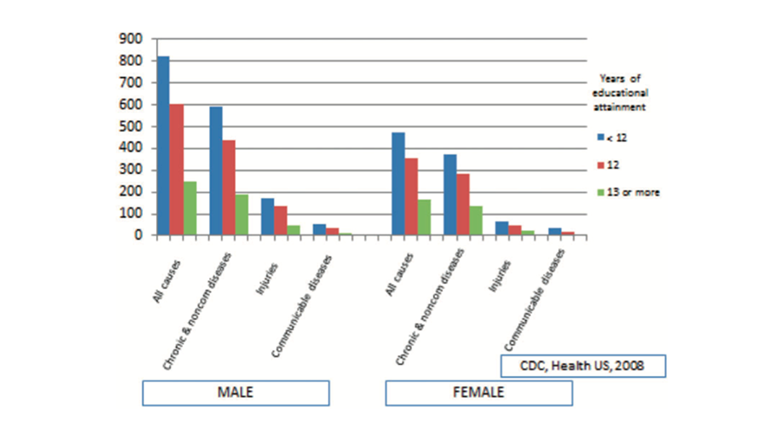

Education is perhaps the core driver of the health of populations, the area in which we must invest to create healthier future generations. Lack of quality education can exacerbate health disparities between groups, increase vulnerability to a range of diseases, and shorten life expectancy (Figure 2).

Hahn RA, Truman BI. Age-adjusted death rates among persons ages 25—64 years for several condition groupings, by sex and educational attainment. Selected US states, 1994—2005. International Journal of Health Services. 2015; 0(0): 1—22.

Education also has an intergenerational effect on health, with lack of education linked to higher rates of infant mortality. There are a number of reasons why the better educated enjoy better health. Principally, education is linked to income and all the attendant health benefits that come with earning more money. Education may also be linked to better life choices and the avoidance of risky behavior. Broader investment in early education represents a chance to expand access to education and to maximize its influence on the lives of the young, as amply shown by a 25-year follow-up of the Brookline Early Education project. With minority students at a frequent disadvantage compared to white students, the promotion of education is deeply tied to the promotion of equity. A resolution to double down on our investment to ensure quality accessible education for all stands to be a clear engagement with a foundational driver of health, maximizing the return on our investment in the health of populations.

5. Prevent violence and mitigate its consequences.

Time and again, throughout 2016, we have seen how guns have enabled hate-filled individuals to carry out acts of mass murder in the US. In addition to these high-profile acts of terror, thousands upon thousands of gun-related incidents add up to an annual count of injury and death that is truly staggering. Indeed, there is little sense in talking about the reduction of violence in our society without talking about gun control. The proliferation of guns in the US not only gives hate a voice, it creates the conditions for widespread accidental death and injury, often involving children. I have written many times before about this violence, and how it is tied directly to legislative inaction at the federal level. This inaction is not only a failure to mitigate this problem through commonsense reform; it is a failure to even study it, as exemplified by the current ban on CDC gun research funding. Gun violence is a clear and present threat to the health of all Americans in every part of America—at home, at work, at play. If we are serious about promoting health, there is no better or more necessary resolution than to start 2017 by addressing the problem of gun violence in this country through meaningful legislative action.

6. Invest in substance abuse prevention.

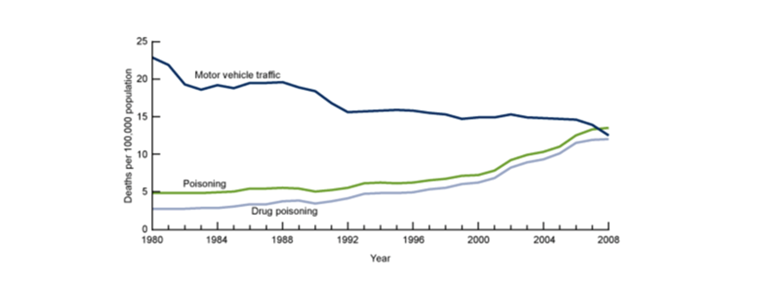

The opioid epidemic has become a familiar and devastating crisis in the US. Globally, close to 5 percent of total years of life lost have been attributed to alcohol and illicit drug use, with opioid dependence the primary driver of the burden of illicit drug use. In the US, close to half a million Americans died from drug overdoses between 2000 and 2014. The scope of this problem is perhaps best illustrated by Figure 3, which shows how, for close to a decade, drug-related deaths have exceeded motor vehicle deaths.

M Warner, LH Chen, DM Makuc, RN Anderson, AM Miniño. Drug poisoning deaths in the United States, 1980–-2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2011; 81(22): 1—8. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db81.htm

The scope of the crisis agitates for solutions that are creative, comprehensive, and solidly grounded in effective preventive strategies—from education campaigns, to making overdose prevention medication more widely available and teaching people how to use it. It is heartening to see that steps are already being taken in this direction. From recent Massachusetts legislation that targets the opioid epidemic, which includes a number of preventive measures, to similarly sweeping legislation at the national level, to trade negotiations to stop the flow of fentanyl into the US, and awareness-raising efforts like last September’s Prescription Opioid and Heroin Epidemic Awareness Week, we have begun rising to meet this challenge. The next step is to confront the stigma associated with addiction, engage more empathetically with people who struggle with this disease, and, in doing so, embrace lifesaving measures, like safe injection sites, which stigma has so far precluded us from widely adopting. A resolution to make substance abuse a priority, a health priority, stands to create real progress towards minimizing preventable harms to our collective health.

These steps, if broadly applied, could go far towards creating a healthier world. Will we see progress on any of these in 2017? I am not sure, and certainly the political shifts in recent months suggest that it will be challenging indeed to do so. This means that it is truly “on us” to tackle these issues, to elevate their visibility, to hold ourselves as a society accountable. We as a school engage these issues daily, with our faculty, staff, and students working on promoting gender equity, addressing the challenge of income inequality and poverty, and engaging with the problem of gun violence among much other work in these areas.

I conclude with my New Year’s resolution. My resolution is to make sure that I do all that is in my power to always create the best possible conditions for our community to innovatively tackle these issues, to generate scholarship that shifts the national and global conversation and leads to change, to equip the next generation with useful knowledge to tackle these issues in their time, and to facilitate efforts that bring action to our local and global community.

I hope everyone has a terrific start to the year. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Professor, Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Eric DelGizzo for his contribution to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.