Where You Live Is Associated with Your Ability to Conceive.

Where You Live Is Associated with Your Ability to Conceive

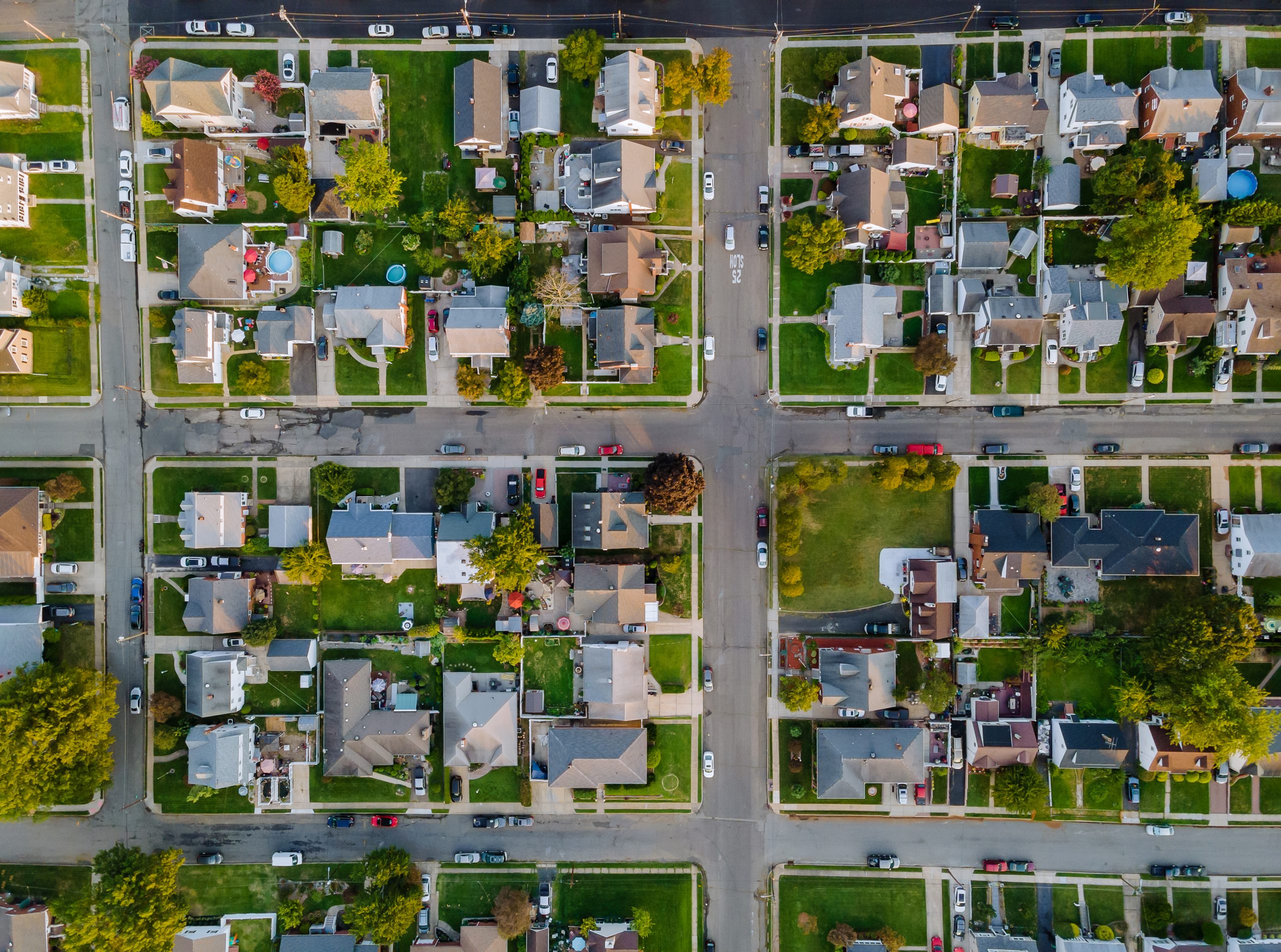

A new study has found that living in socieconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods is linked to reductions in fertility.

People who live in socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods, as measured by the “area deprivation index,” were about 20 percent less likely to conceive in any given menstrual cycle than those living in neighborhoods with more resources, according to a new study led by researchers at the School of Public Health and Oregon State University.

Published in the journal JAMA Network Open, the study measured fecundability, which is the monthly probability of conception among couples who are not using contraception.

“Fertility researchers are beginning to examine factors associated with the built environment,” says study lead author Mary Willis, an assistant professor of epidemiology at BUSPH.

Public health research in the last decade has highlighted the importance of social determinants of health and the idea that ZIP code is the greatest predictor for overall life expectancy, based on factors such as income, healthcare access, employment rates, education level, and access to safe water.

“But the concept that your neighborhood affects your fertility hasn’t been studied in depth,” Willis said. “In addition, the world of infertility research is largely focused on individual factors. As an environmental epidemiologist, I think it is also important to examine structural and neighborhood-level factors.”

“Pathways by which neighborhood disadvantage may reduce fecundability include lack of access to societal resources—such as healthy foods in grocery stores and access to green space—as well as greater levels of perceived stress and stress hormones, many of which have been associated with reduced fertility in some studies,” says study senior author Lauren Wise, professor of epidemiology.

The study leveraged data from Boston University’s ongoing Pregnancy Study Online (PRESTO). Researchers analyzed a cohort of 6,356 individuals ranging from 21 to 45 years old, attempting to conceive without the use of fertility treatment, in data compiled from 2013 through 2019. Study participants filled out online surveys every eight weeks for up to 12 months, answering questions about menstrual cycle characteristics and pregnancy status. During the study period, 3,725 pregnancies were documented.

The researchers compared participants across different area deprivation index rankings at both the national and within-state levels, which used socioeconomic indicators including educational attainment, housing, employment and poverty.

They found that participants in the most-deprived neighborhoods based on the national rankings had a 19-21 percent reduction in fecundability compared with those in the least-deprived neighborhoods. Based on within-state rankings, the most-deprived neighborhoods saw a 23-25 percent reduction in fecundability compared with the least-deprived areas. The majority of people in the cohort were white, had completed a four-year college education, and earned more than $50,000 a year.

“The fact that we’re seeing the same results on the national and state level shows consistency of the associations between neighborhood deprivation and fertility,” Willis said.

Approaching fertility research from a structural standpoint might help reduce or prevent infertility overall, she said, especially because fertility treatments are costly and inaccessible to many couples.

The study findings indicate that investments in deprived neighborhoods to address socioeconomic disparities may yield positive benefits for fertility, but future work would be needed to determine what the best policies or program could be.

At SPH, the study was coauthored by Elizabeth Hatch, professor of epidemiology; Amelia Wesselink, research assistant professor of epidemiology; and Collette Ncube, assistant professor of epidemiology. Additional coauthors include Olivia Orta of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice; Renee Boynton-Jarrett, associate professor of pediatrics at Boston University School of Medicine; Lan Đoàn of New York University; and Kipruto Kirwa, assistant professor of public health and community medicine at Tufts University.