Explaining the New 988 Mental Health Crisis Hotline.

Explaining the New 988 Mental Health Crisis Hotline

Sarah Lipson discusses the new prevention hotline, which experts call a game changer, connecting callers with trained counselors for suicide, excessive drug use, or other mental health emergencies.

A version of this article originally appeared in BU Today.

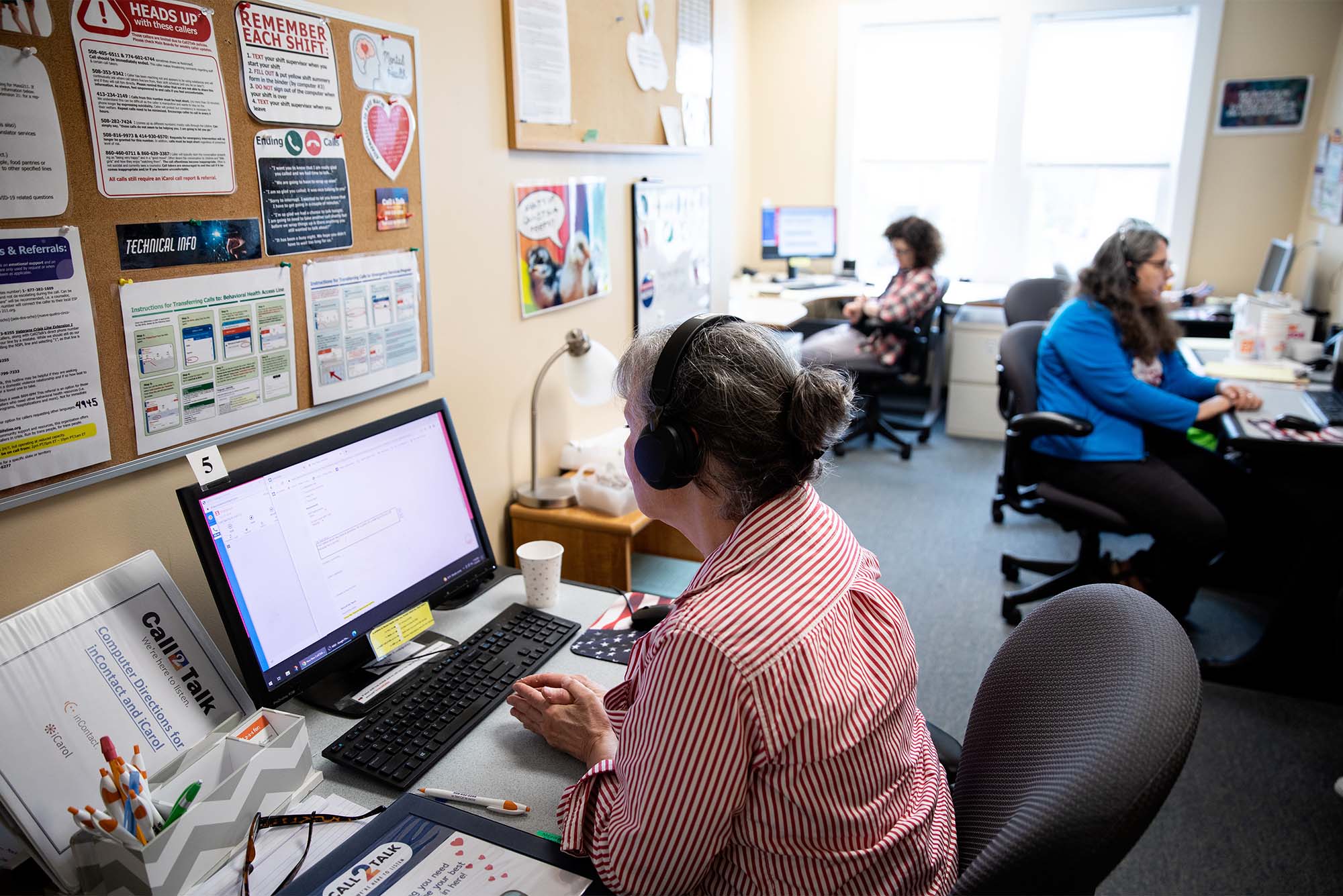

Earlier this summer, the United States began rolling out a new number to call for anyone experiencing a mental health or addiction crisis. By dialing 988, callers are put in touch with a trained mental health counselor at one of 200 crisis centers across the country.

The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline replaces the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, which launched in 2005, but was chronically underfunded. The new, three-digit number is far easier to remember in a crisis than the previous 10-digit number and the new name reflects the expansion of the program to provide support not only to those experiencing suicidal ideation, but also to anyone dealing with any kind of mental health or addiction emergency.

Funded by more than $400 million in federal dollars, the new hotline is being billed as the 911 of mental health. Some experts say it’s a game changer in the nation’s efforts to address a growing mental health crisis that was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The number of suicides rose from 29,350 in 2000 to 45,979 in 2020, and the number of drug overdoses reported last year climbed to more than 107,000—a record. A School of Public Health study reported that nearly a third of all adults in the United States experienced elevated symptoms of depression in 2021—underscoring the need for the expanded service.

BU Today spoke with two mental health experts—Christine Crawford (SPH’09), a School of Medicine assistant professor of psychiatry and the associate medical director for the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), and Sarah Lipson, assistant professor of health law, policy, & management at SPH and principal investigator of the Healthy Minds Network, about 988, who it’s designed to help, and why the texting and chat options are particularly important in reaching college-age students.

These interviews have been edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

with Sarah Lipson and Christine Crawford

BU Today: Who should call this number?

Crawford: 988 is a number to call if you have any worries or concerns about your mental health and you’re worried that you’re in a state of crisis: your function has deteriorated, you don’t know what you’re going to do next, you’re noticing that your mood and behavior are getting in the way of your ability to function the way that you typically would, you’re experiencing thoughts of suicide, or you have any thoughts or concerns about hurting yourself. Even friends and family members should call if they want to talk to a counselor about their concerns for a loved one and to learn about what resources are available. Now, when people are feeling a sense of urgency to get help for themselves or other people, all they need to remember are three numbers: 988. Hopefully, it will be just as automatic for people to think about dialing 988 for mental health and addiction emergencies as it is for them to think about dialing 911 for medical emergencies.

In the past, people often called 911 to seek help when a loved one was suffering a mental health crisis, which often precipitated problems. Can you talk about that?

Crawford: There are multiple problems with 911 being the go-to resource if someone is experiencing a mental health crisis. Number one: there are communities that have deep mistrust of the police and a police response to any sort of crisis. Historically, we have seen that interactions between people from communities of color and police can be quite harmful to the individual that may be experiencing the mental health crisis. Given the fact that these communities are aware of the potential risk of their loved one being met with a police officer who has a gun on their body, they’re worried about how that person will interact with them. Because of all that concern and mistrust, they may not call during a crisis and try to manage it on their own. Not calling, not getting that person connected to help, can lead to further delays in their treatment and worsening symptoms.

To know now that a mental health crisis is being met with a mental health response, rather than a criminal justice response, is a positive thing and hopefully will make it so that when people are in the midst of a crisis, they don’t hesitate to dial this number: 988.

Walk me through how the new 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline works.

Crawford: 988 is the one number that people who are experiencing a mental health crisis can call and be connected to somebody who is trained in managing mental health crises and who can put you in touch with the necessary resources in order for you to get the help and support you need in that moment. Only a very small percentage of people who experience mental health symptoms or present a crisis require the kind of level of care of having to go to an inpatient unit. People can call this number and be put in touch with community-based support. That doesn’t automatically mean being seen by someone like me, a psychiatrist, for medication management. That could be connecting someone with a peer specialist, which is an amazing movement that really has been a part of the recovery model in mental health, in which a person with experience connects with the individual and talks to them about how they navigated the system, talks to them about how they managed their own symptoms and have been able to live a meaningful and productive life. Calling 988 could also connect you to licensed mental health counselors or licensed independent clinical social workers. Those are just some examples of other resources that people can be connected with.

The US Surgeon General has labeled mental health a “devastating crisis among young people.” Can you talk about what we’re seeing in this age group and why teens and college-aged students are particularly vulnerable to mental health issues?

Lipson: The traditional college years—18 to 25—directly coincide with the onset for mental health problems; 75 percent of lifetime mental health problems will onset by the mid-20s, meaning many students experience their first signs and symptoms while in college. In our annual Healthy Minds Study data—collected from over 500,000 students at more than 500 US colleges and universities—we have seen that the prevalence of mental health problems is high and rising. In our most recent national data, from 2021, 41 percent of students met criteria for major depression, 34 percent for generalized anxiety, and 13 percent reported seriously considering suicide in the past year. Relative to 2013, this represents a 135 percent increase in symptoms of depression, 110 percent increase in anxiety, and 64 percent increase in suicidal ideation.

Crawford: We’ve been seeing an increase in symptoms around depression and anxiety, as well as young people presenting with trauma-like symptoms, given the trauma they’ve experienced losing loved ones to COVID, as well as the racial trauma that a number of communities have experienced over the last couple of years. As a young person, you’re growing up during this time, in a very critical time in your development where you’re trying to understand your place in the world, and to know that your world is unsafe, that there isn’t a sense of certainty about the future, really has had profound impacts on our youth mental health.

The new 988 number allows people not just to call, but also to communicate via text and chat. Why is having a digital component so important in persuading young people in crisis to reach out?

Lipson: In general, expanding the “menu” of mental health options is a priority for meeting the needs of adolescents and young adults, a generation of digital natives. This menu needs to span the continuum of mental health—from wellness promotion to crisis services. The menu also needs to allow for communication in varied formats—from individual, in-person counseling to peer support in group settings to texting. The more options and modalities on the menu, the more likely that young people’s needs and preferences will be met. Particularly when it comes to crisis services, the ability for people to not only call, but also text and chat is important for reducing barriers to outreach.

Crawford: Having a digital option is critical for a number of reasons. Number one, when it comes to teens, they’re quite used to texting and there’s a certain level of comfort that they have communicating and articulating what they’re experiencing and feeling through text, rather than doing so over the phone. For a lot of teens, there may be some anxiety built into a phone call. There are worries about how they’re going to be viewed or judged by the sound of their voice or what have you. Given that 988 is trying to increase access to mental health services and resources, we want to use a form of technology that is easily accessible by our youth. There’s also the issue of privacy and confidentiality. It’s much easier to text this number when you’re living in a home with family members or sharing a room on campus with multiple roommates. Texting or chatting allows you to still get your mental health needs met and be connected with the necessary resources without everyone eavesdropping on your conversation.

How important is this new lifeline for young people experiencing a mental health or addiction crisis?

Lipson: The college mental health “crisis,” as many refer to it, is not just a crisis of prevalence, it’s also a crisis defined by significant levels of unmet mental health needs and inequalities in terms of who is able to access service and treatment. In our Healthy Minds data, we have documented a large mental health “treatment gap,” defined as the proportion of college students with a positive screen who have not received treatment. For example, among students who meet criteria for symptoms of depression and/or anxiety, just 38 percent received mental health services (a 62 percent gap). Many students with untreated symptoms report positive attitudes about mental health, have high levels of knowledge about resources, and believe that treatment is effective. They report willingness to engage in mental health services, but the task of seeking help appears subject to inertia. The most salient barriers among students with untreated symptoms are: lack of time, questioning how serious one’s needs are, and thinking the problems will get better on their own. Students often delay seeking help until they are in a crisis, which underscores the need for a public health approach to mental health in higher education, as well as the need for accessible services, like 988.

Is this new lifeline a game changer in addressing the nation’s mental health crisis?

Crawford: Yes. Oftentimes, as a psychiatrist, what I see is that people have a lot of worries and fears about engaging with the mental health system. A lot of that has to do with experiences that they’ve heard from others about what happened to them during a time of crisis. If this can make it so that people’s first interaction with the mental health system is a positive and supportive one that has a trauma-informed approach, my hope is that that will lead people to want to voluntarily engage with the system to prevent a worsening of mental health symptoms and the development of more severe psychiatric conditions. To know that a mental health crisis is being met with a mental health response, and not a criminal justice response, is certainly a positive thing. And to know that there is a dedicated resource available for everyone, no matter which part of the country you live in, to discuss matters of mental health, demonstrates to everyone that mental health matters just as much as your physical health and it matters just as much as a physical medical emergency.

Those seeking confidential mental health counseling can also contact Student Health Services Behavioral Medicine, the Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, the Center for Anxiety & Related Disorders, the Samaritans of Boston suicide hotline, and BU’s Faculty & Staff Assistance office.