The Other End of the River.

A version of this story first appeared on the BU Research site.

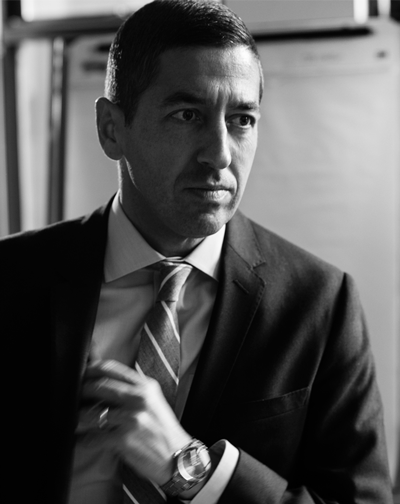

Sandro Galea and the future of public health

Sandro Galea stood with his backpack at the edge of a small airstrip in Mendi, Papua New Guinea, wondering what to do next. It was summer 1992. Months before, the 21-year-old second-year medical student at the University of Toronto had written to 84 remote hospitals, volunteering his services for the summer. “I wanted to be a doctor where I was really needed,” he says. “I wanted the best possible training to do ‘out there’ medicine.” He received eight responses, including a welcoming letter from a hospital director in Mendi—“the middle of the middle of nowhere,” says Galea—so he booked a ticket. He arrived in a tiny plane crowded with Australian miners, all wearing identical red company T-shirts.

“The Australians get off the plane, and they have their company van waiting for them,” recalls Galea. “I got off the plane wondering how to get to the hospital.” He hitched a ride in the back of a pickup truck, and spent the summer working with a Canadian physician and his wife in rural Ialibu, deep in the Southern Highlands. Galea was out there, and he loved it. “It was wild,” he says. He later chose a residency in Thunder Bay, 14 hours north of Toronto, where he met like-minded fellow resident Margaret Kruk, now his wife. After their residencies, the two, aiming for careers in rural medicine, worked in remote Geraldton, Ontario, population 3,000. Then, looking to practice “more extreme medicine,” as Galea puts it, they signed up for a stint with Doctors Without Borders. Kruk went to Lebanon and Galea to Somalia, where the organization’s previous doctor had been shot and killed. He worked in Somalia for a year, setting broken bones, prescribing malaria pills, and treating gunshot wounds, escorted by guards carrying Kalashnikov rifles.

“Sandro and I both gravitate toward the hardest thing, where we’ll be challenged and have the biggest opportunity for impact,” says Kruk, associate professor of global health at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “We thought this was the greatest adventure.”

But something happened to Galea in Somalia. “It was there that I got this feeling, like I’m standing on the side of the river, pulling people out,” he says. “I was doing that over and over and over again. And I felt I was doing a lot of good, but I also knew that once I left, the same thing would keep happening. So I really wanted to understand who was throwing people in the river to begin with.”

Galea looked around and spied his true path, perhaps the only one more challenging than saving lives in remote Ontario or ravaged Somalia. He switched careers, leaving the immediate gratification of medicine to labor in the vineyard of public health.

In 2015, Galea—after an MPH at Harvard, a DrPH at Columbia, and a meteoric rise through the academic ranks—became the dean of the BU School of Public Health, the third in the school’s 40-year history. At 44, he is the youngest public health dean in the country, and he has taken the already well-regarded school—ranked 10th nationally—and infused it with near-palpable electricity. In the past year he has put his stamp on a new MPH curriculum, retooled the school’s website, launched three lecture series, begun a globetrotting speaking tour, written reams of essays, and coauthored a forthcoming book. Colleagues describe his leadership as both exhilarating and exhausting.

“Sandro is a dynamo. He has more energy than any person I’ve ever encountered, of any age,” says Lisa Sullivan (GRS’86,’92), an SPH professor of biostatistics and associate dean for education. “He’s exactly what we needed. Things had been going great at the school—we had all the pieces. But Sandro put them together to raise us to the next level.”

Galea’s goal is to not only take BU to the forefront of public health, but to take public health to the forefront of American discourse. “Public health is emerging into the world in a very exciting way,” he says. “If you’re in this field, you need to accept that you’re doing small things that make change over decades. If you want immediate impact, you should be in medicine. What I really care about is us becoming part of the social momentum.”

Don’t Just Sit There and Count Things

Public health can be a hard sell in a country that cherishes individual freedom and personal responsibility—witness the cries of “nanny state” when former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg tried to ban oversized sodas. But it wasn’t always this way. In the early- to mid-20th century, wide swaths of America welcomed campaigns for a polio vaccination and clean water, which proved enormously successful. True, the country was perhaps more united in those days, and people had seen polio and filthy water firsthand, but these programs prospered for another, more subtle reason: because Americans realized that they improved the health of everyone, without exception.

But today, argues Galea, public health must shift its focus, necessarily, to the exceptions: people marginalized by poverty, with limited access to health care, exposed to violence and racism that many Americans cannot fathom. “It’s the social divides that cause health divides. The right approach is to tackle the social divides, not the downstream medical consequences,” says Galea, who is fast becoming a leading national voice on these issues. “Income inequality is a direct result of policies that we accept and embrace in society. We can reverse it, if we have the political will, vision, and clarity.”

He began to form these views in medical school, volunteering in a night van helping homeless youth. The experience gave him a deep empathy for marginalized populations and insight into the complex social factors that determine health. “It was revelatory,” he says. “I think I just found purpose.”

As dean, Galea continues to address thorny social issues that impact public health—for instance, mass incarceration in the US criminal justice system. In his March 22, 2015, Dean’s Note—his weekly topical letter to the SPH community—he argues that we should consider mass incarceration a disease: one that disproportionally targets people of color, barring them from social welfare benefits, worsening the transmission of TB and viral hepatitis, encouraging drug use, and increasing mental illness, among other health effects.

Working with Harold Cox, associate dean for public health practice, Galea arranged Dean’s Symposium—a full day of lectures and discussion, held quarterly—called Beyond Ferguson, which examined policy changes that could address inequities wrought by the criminal justice system—for example, advocating that the federal government allow convicted felons access to public housing and student loans. “These are controversial topics, and we should be addressing them,” says Cox. “And we have a dean who believes this as well.”

But for some public health professionals, this is shaky territory. In a February 2016 essay in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Galea and colleague George Annas call for bold advocacy, but acknowledge the peril: it’s one thing for doctors and epidemiologists to collect data on vaccinations and urge patients to stop smoking, and quite another to campaign for immigration reform and fair sentencing laws.

“Sandro thinks we should be out in the world. If we have something to say, we should say it,” says Annas, a William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor, an SPH professor, a School of Medicine professor, and a School of Law professor. “Enter the public arena, for God’s sake. Don’t just sit there and count things.”

But just as Galea pushes for public health to intervene more broadly in society, its slice of the funding pie is shrinking. Precision medicine, with its promise of personalized treatment and wonder cures, has captured the imaginations of many, including President Obama, who pledged $215 million for his Precision Medicine Initiative in January 2016. Silver bullets are always sexier than incremental policy change. And less sexy can mean less fundable.

When the subject of federal funding pops up, Galea likes to whip out a stack of index cards printed with colored pie charts, graphs, and dense statistics. (He keeps several sets of index cards for different topics.) With impressive recall and great speed, he points out that in fiscal year 2015, the National Institutes of Health gave only the tiniest sliver of funding—just .4 percent—to projects with “population” or “public” in the title. Meanwhile health care spending per capita rose—another card—while life expectancy—another card—relative to other high-income countries, fell.

“When you’re with Sandro, you always feel like you’re playing catch-up, because he sees things so quickly. You definitely need to be awake or you will be left in the dust,” says his Columbia colleague Roger Vaughan, a Mailman School of Public Health biostatistics professor and vice dean for academic advancement. “If Sandro could replace one body part, it would be his mouth, because it can’t keep up with his brain. He needs a higher throughput device.”

The Public Face of Public Health

Galea regularly pours his ideas into writing, publishing letters, articles, and opinion pieces in media outlets like the New York Times, the Boston Globe, and Forbes, and posting lengthy Dean’s Notes each week on topics like gun control and homelessness. He has also become a familiar presence at SPH events, dressed always, and impeccably, in elegant tailored suits with silk handkerchiefs.

At work Galea is hyperorganized and ruthlessly efficient—he runs meetings to the minute, responds to all emails within 24 hours. His office is spotless, uncluttered, and paper-free. He drinks no caffeine. Despite all this, people actually like him. Because beneath his Spock-like exterior beats the heart of Bono. “He believes in what we’re doing. He wants to make the world a better place,” says Sullivan. “I know it sounds naïve and cliché, but it goes really deep for him.” Galea also tempers his intensity with genteel charm and self-deprecating humor. Introducing a Dean’s Seminar on immigration reform, he noted that he is an immigrant twice over: a native of Malta, he moved to Canada at age 14, then to the United States in his late 20s. “I like the fact you call us ‘aliens,’” he said. “Don’t think we haven’t noticed.”

While Galea appreciates his turn at a bully pulpit—“it’s an extraordinary privilege to be paid to contribute to thought,” he says—he has yet to embrace his role as a personality. “It’s not about me; it shouldn’t be about me,” he says. “I’m constantly asked to describe my personal narrative, and I understand why it serves the institution, but it makes me deeply uncomfortable.”

Squirmy, in fact. When answering personal questions, his demeanor changes, softens: he talks slower, looks down, blushes. As quickly as possible he steers the conversation back to issues, strategy, and statistics—where are those index cards?—and settles comfortably back into wonk mode.

“Sandro doesn’t dwell on his personal successes,” says Kruk. Even now, after nearly two decades together, she says, if Galea publishes a paper or wins an award, he’ll send her a text message that begins: “I’m a little embarrassed to say this, but…” She says, “that’s a pretty common text.”

An Extraordinary Responsibility

On a Tuesday in February, about 20 SPH leaders—department chairs, center directors—gathered around a gleaming boardroom table for their bimonthly meeting. Galea sat at the head. His leadership style tends toward pragmatic vision and team building; throughout the meeting he listens attentively, not dominating the conversation, but often nudging it back on track.

“He’s open to disagreement and honest debate, but he will draw the line when needed,” says Wendy Mariner, Edward R. Utley Professor of Health Law, who cochaired the SPH Strategic Thinking Initiative, a series of discussions among students and faculty to map the school’s future. “The most important thing for me is that I know I can have a reasoned argument with him.” Mariner, a member of the SPH faculty for decades, says Galea has reinvigorated the school, adding, “I keep waiting for the other shoe to drop, but it hasn’t.”

Galea told the deans and directors around the table that Victoria Parker (DBA Questrom’97), an SPH associate professor of health law, policy and management, had asked her students to list qualities of good and bad leaders. He read the list to the assembled group. When he finished the qualities of bad leaders—short-tempered, no agenda, too critical—somebody quipped “sounds like the presidential candidates” as the room erupted in laughter. Then Galea said, “When Professor Parker passed this along, because I’m Catholic and driven by guilt, I went through the list and judged myself line by line. I’m not saying you should all do this, but it might be a useful exercise.”

“Sandro thinks we should be out in the world. If we have something to say, we should say it. Enter the public arena, for God’s sake. Don’t just sit there and count things.” George Annas

This compulsive evaluation and analysis are an integral part of Galea’s intellectual life, as well. Knowing that a school full of lefty do-gooders can easily become an echo chamber, he seeks out contrarian opinions that question the status quo. At the Beyond Ferguson symposium, he invited several conservatives to sit in the audience and challenge the liberal groupthink. In February, he flew to Washington, D.C., to host a dinner for health policy leaders from conservative think tanks, including the Heritage Foundation and the Cato Institute.

“It was the best dinner ever!” Galea says. “Conservatives hate public health. They hate public health with a visceral hatred, the way a child whose pet bunny died hates all bunnies. And they hate public health for two reasons. Number one: they feel like public health has a value set that they don’t agree with. But they also say that we use data only to serve our ends, to impose upon them regulation and policies that they don’t agree with.

“What emerged for me is that public health needs to be much more honest, much more straightforward,” he adds.

Galea measures himself by the same yardstick of relentless honesty. “I am driven by a profound sense of privilege, good fortune, and luck,” he says. “I have an extraordinary responsibility to fully capitalize on that. And falling short on that is unacceptable.” One of his habits: while commuting home, he reviews his top three failures of the day. “You’d think I could be trained like an organ monkey to make mistakes only once,” he says, “but no, I make the same mistakes over and over.”

Galea mentions this while speaking to a group of physicians and scientists at a Mid-Career Faculty Leadership Program. A moment later, a young physician in the audience raises her hand. “When do you focus on what you did right?”

Galea looks surprised, then genuinely stumped. “Hmm. I don’t know. Wow. Good question. I guess I don’t do that. I have very little time so I just focus on my mistakes, and what I could have done better. But now that you’re saying it that way, it sounds pathological.” He pauses, brow furrowed. For once, he is speechless.

Then he brightens. The clouds of doubt scatter. “Life is short,” he says. “I need to get things done.”

Barbara Moran can be reached at bmoran@bu.edu.