19th Century Waterworks Awes 21st Century BU Group

By SRFS Board Members Kevin Carleton and Gerald Clarke

Generations of faculty, staff, students, and alumni of Boston University have traveled west on Beacon Street, through Cleveland Circle and past the beautiful Chestnut Hill Reservoir on their right. Many have taken this route to attend athletic matches between teams from the University and its crosstown rivals at Boston College.

Along the way many likely have noticed the magnificent late-19th century structure on the south side of Beacon Street that, especially to the experienced eye, might seem to be the work of Henry Hobson Richardson, the architect of Trinity Church in Copley Square. This building, designed in two stages, was actually built under the supervision of two City of Boston architects, using Richardson’s Romanesque style but with a more down-to-earth purpose: it served as the High Service Pumping Station to provide Boston with a safe and consistent water supply, one of the first in the nation to operate on this scale.

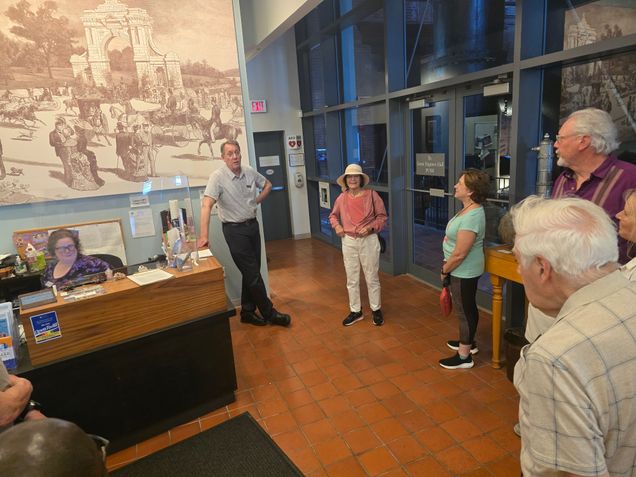

Today, the building is the home of the Metropolitan Waterworks Museum, which was established as a non-profit educational organization and opened to the public in 2011. On June 12, nearly two dozen retired faculty and staff, along with their guests, were given an in-depth tour of the facility, led by museum Executive Director Eric Peterson.

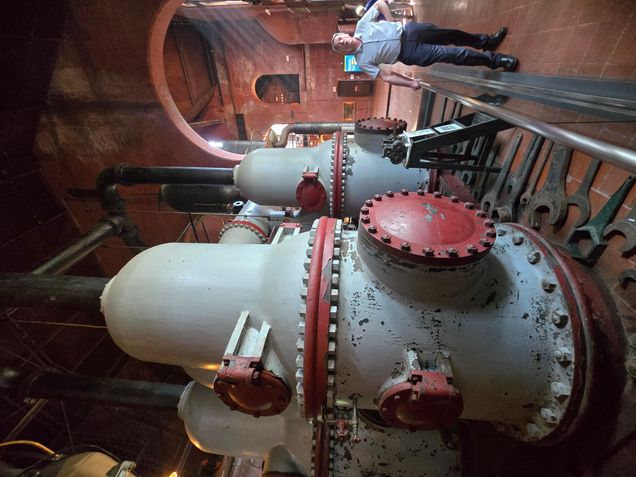

Both the building and the machinery within were designed in an age when esthetics mattered almost as much as utility. The various pumps – some several stories in height and weighing many tons – seem almost to be works of art as well as mighty tools, built to pump enormous quantities of water to a city growing in size, as well as in height.

Peterson recounted the history of water sources for Boston, from its founding in 1630 to the present. Early settlers benefitted from a plentiful supply of spring water, but over the decades it became inadequate for a growing population and subject to contamination, thanks to a lack of any kind of system to manage human and animal waste. Jamaica Pond was tapped, but demand quickly outgrew supply. The Great Fire of 1872 underscored the need for a reliable supply of water, with sufficient pressure to meet the needs of a fire protection service and of a city with ever taller buildings.

(The 1872 fire destroyed many buildings owned by the founders of Boston University, buildings that formed BU’s initial endowment, wiping out what had been one of the largest higher education endowments in the country at the time.)

The Boston Water Board was formed in 1876, and by 1880 the Board appealed to the Boston City Council for funds to build a pumping station adequate to serve the growing needs of the city. Approval was finally granted in 1884, and the station became operational in 1887, in the building designed by Arthur H. Vinal. Initially, it featured two Holly-Gaskill coal-fired pumping engines, each with a capacity of eight million gallons per day. The building was enlarged in 1897 under City Architect Edmund March Wheelwright. This addition housed the Allis pump, a monster that could put out 30 million gallons each day. This machine rises three stories above the ground floor, and extends two stories into the basement. It features two flywheels, each weighing 25 tons. Participants in the BU tour were granted access to platforms at different levels to view the workings of this great machine.

The primary source of water was the Chestnut Hill Reservoir across Beacon Street. This man-made lake was dug out of wetlands between Beacon and Commonwealth Avenue. Before 1950, there were actually two bodies of water: the one that exists today was originally known as the Bradlee Basin, named for Nathaniel J. Bradlee, then the president of the Cochituate Water Board (water was pumped into Boston from Lake Cochituate in Framingham); the other was known as the Lawrence Basin. By 1950, this smaller basin was taken offline, refilled with soil, and sold to Boston College, which now uses the land for its stadium and other athletic facilities.

This property, site of the Lawrence Basin, had been owned by Amos Adams Lawrence, a leading Boston businessman, who sold 58 acres to the city. Lawrence is known to today’s University community as the man who built the estate in Cottage Farm, Brookline, that now serves as the home for presidents of BU.

The reservoir and pumping station went offline in the 1970s, although the reservoir can be tapped when needed.

The Waterworks Museum is open to the public Wednesday through Sunday from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Admission is free, but donations are welcome. Free guided tours are offered at 11:15 a.m., and in the afternoon at 12:30 and 2. Special Access Tours cost $18 per person. The museum is located at 2450 Beacon Street, Boston. Telephone 617/277-0065, online at www.waterworksmuseum.org.