Then and Now: SPH Founders and First Faculty Reflect on School’s Early Years.

Then and Now:

SPH founders and faculty reflect on the school’s early years.

In March 1976, a brief letter from Boston University School of Medicine (now the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine), double-spaced and composed on an IBM Selectric typewriter, officially announced the establishment of a part-time evening program leading to a Master of Public Health. Four hundred copies were run off on a Xerox copier the size of a dining table and mailed to administrators and personnel directors at hospitals and health centers throughout New England, marking the modest start of what would eventually become the BU School of Public Health.

That fall, 54 degree-seeking students and 20 nondegree students began taking public health courses in the Department of Socio-Medical Sciences and Community Medicine. According to Leonard Glantz, who taught health law at the schools of law and medicine and became one of the first faculty members at the nascent public health school, a major aim of the department was to counter the then-prevailing method of training medical students to think narrowly about individual patient health.

“Socio-medical sciences were about how social factors had an impact, and that doctors needed to understand the environment in which they were working, not just understand their patients,” says Glantz, who later became professor emeritus of health law and associate dean for academic affairs. “Socio-medical sciences taught epidemiology, biostatistics, health law, and health systems—and all the things that medical students weren’t taught about any place else.”

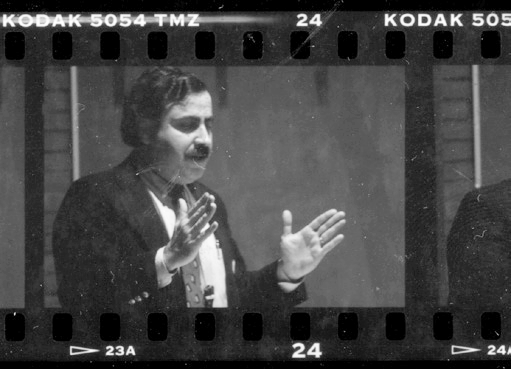

Dr. Norman Scotch, the first director of SPH, was chair of the Department of Socio-Medical Sciences and Community Medicine and one of the catalysts for developing a school that prioritized training healthcare workers and emphasized the social determinants of health. Scotch, who died in 2014 at age 86, was born in Dorchester to working-class immigrant parents from Lithuania and Russia. He enlisted in the US Army in 1946 and later enrolled in Boston University on the GI Bill. His modest upbringing influenced his understanding of the difficulties faced by public health professionals who wanted additional training but couldn’t leave their jobs.

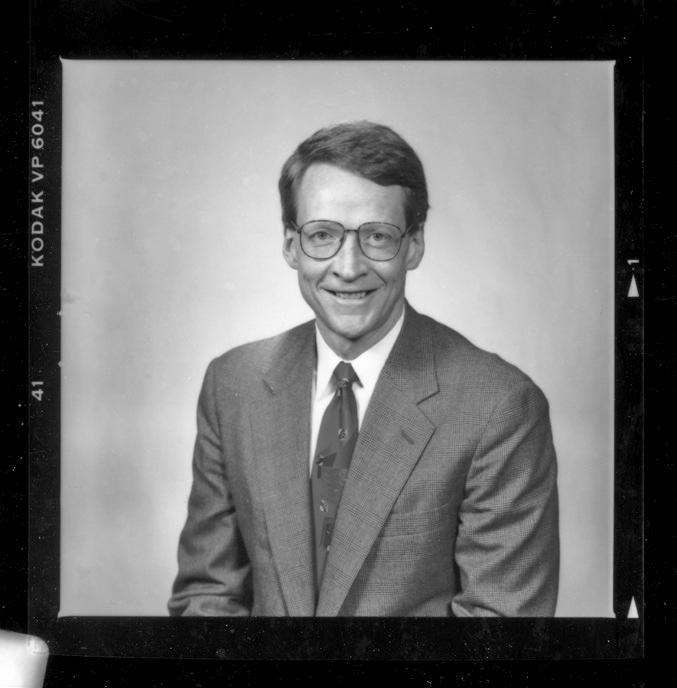

Former Dean Robert Meenan, the second head of the school, also had a blue-collar upbringing in Cambridge, where his father was a mail carrier. Meenan graduated from Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine in 1972 and trained as an internist at Boston City Hospital (now Boston Medical Center). After completing a rheumatology fellowship in San Francisco and an MPH at UC Berkeley, he returned to Boston for a new challenge.

“I came back as a faculty member in the medical school in 1977, and the school was up and running, such as it was. I mean, it was still pretty much of a fly-by-night operation, pun intended,” Meenan quips. Establishing the MPH degree as an evening program was an extension of the school’s original design to provide master’s degrees for those already working in public health.

“The idea was, not surprisingly, that there are tons of people out there working in public health, but a relatively small number of them actually had real credentials,” Meenan says. “And that was very responsive to the long-term mission of the Boston University Medical Campus, which was to help serve the surrounding community and the people in that area.”

Meenan points out that choosing to start as an evening-only program was also a savvy business decision because it enabled the medical school to maximize available space; classes for medical students started early and usually ended by mid-afternoon. Public health classes were organized as one meeting per week for three hours, with most starting at six in the evening to give students enough time to travel from their day jobs and possibly have a quick dinner.

David Ozonoff, now emeritus professor of environmental health, taught sociology and the history of science in the Department of Socio-Medical Sciences. He recalls a memorable lunch in the late 1970s with Isaac “Ike” Taylor (father of folk singers James and Livingston Taylor), a former dean of the University of North Carolina Medical School, when Taylor was nearing the end of a distinguished career and had returned to Boston to help establish the cancer center at BU’s medical school.

“Ike said starting a new school of public health the way we were doing it is a really hard job,” Ozonoff recounts. “People don’t realize when they start what a tough job it is to launch a new school of any kind. It’s really a heavy lift.”

A few of the earliest faculty members remember the hours of organizational meetings and other preliminary correspondence to navigate the multiple bureaucracies at the medical school, the University, and external accrediting bodies. In 1978, the modest program was designated as a School of Public Health within the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, with five departments: Health Research and Evaluation; Public Health Law; Healthcare Systems; Social & Behavioral Sciences; and Environmental Health. “We were at the beginning of it all at that time, and I heard what [Ike] had to say, but I don’t think I felt it in my bones the way I did a few years later when I was fully engaged in doing the heavy lifting,” Ozonoff adds.

Renowned bioethicist George Annas, William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor at Boston University and director of the Center for Health Law, Ethics & Human Rights at SPH, says he and Glantz didn’t intend to spend the bulk of their careers at the emerging public health school. Annas was the director of the Center for Law and Health Sciences at BU’s School of Law for several years before issues arose concerning the center’s future home.

“The law school was never all that thrilled with it. No law schools are, even though they get ranked in U.S. News & World Report on their health law programs,” Annas says. “But Norman Scotch was very welcoming. We had no idea what he would think about it, and he basically invited us over to the medical campus, Leonard and I both, and we were happy to go. He was a delight to work with.”

One of the earliest challenges the new school faced was establishing an academic culture inde-pendent of the medical school, with enough rigor to attract scholars who were making names for themselves. In 1980, Theodore “Ted” Colton was one of those up-and-coming researchers and left the faculty at Dartmouth College Medical School to become the founding chair of the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at SPH.

“I think there was a great deal of prejudice among the existing schools of public health against upstart schools such as ours, which was essentially a night school,” Colton says. “Of course, the irony of it is that so many schools over the next few years began the same way.”

In 1981, the school expanded admissions and course offerings and began admitting full-time students. One of Colton’s first and more important tasks was to help elevate the school’s academic standing by launching the first doctoral program at SPH. “That’s my pride and joy,” he beams. In 1983, the Doctor of Science in Epidemiology was established and enrolled its first students.

When Les Boden arrived in 1985, he was only the fourth faculty member in the Department of Environmental Health. The school had started to outgrow its offices on two floors of an older edifice on the Medical Campus, and several departments were moved to a historic structure that is now SPH’s permanent home, the Talbot Building.

Boden, currently a professor of environmental health, says the last few decades of doctoral students illustrate the school’s growth—and strength. “They’re obviously people who’ll go on to do all sorts of interesting things, and I’m just really impressed by them. And aside from the fact that they’re able to be full time, and they have access to the newer techniques, we’ve just had terrific people come through the program.”

Timothy Heeren, a professor of biostatistics and one of the few early faculty members still at the school, says the student body shifted dramatically as new students were increasingly full time and had recently completed undergraduate study across the US and around the world. “It really changed the way we taught, and who we were teaching. It led to our growth.”

The biggest challenge that SPH faced— starting a school from scratch, with many odds to overcome—may, ultimately, have been a main factor in its eventual success. Now nearing its 50th anniversary, SPH has come full circle by launching a reasonably priced, fully online MPH for working professionals. “Since its founding, SPH has always developed innovative opportunities for people to receive a high-quality public health education,” says Lisa Sullivan, SPH’s current associate dean for education and a 27-year faculty member in the biostatistics department. “With our new online MPH, we can now bring our innovative SPH education to anyone, anywhere.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.