Hey Google, Which Social Distancing Policies Work Best?

Hey Google, Which Social Distancing Policies Work Best?

Analyzing data from Google’s COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports, researchers found that government-mandated stay-at-home orders were more effective than voluntary guidelines in reducing the amount of time people spent away from home at the start of the pandemic.

From states of emergency, to business and school closures and stay-at-home orders, social distancing measures were among the earliest and most important strategies that governments across the world implemented to curb the spread of COVID-19—but the implementation of these measures varied widely from state to state and country to country.

Understanding exactly which policies were most effective at reducing population mobility and COVID case growth could help scientists and policymakers make informed decisions about potential virus trajectories and effective mitigation measures during a COVID resurgence or during a future pandemic, says Gregory Wellenius, director of the Program on Climate and Health and professor of environmental health at Boston University School of Public Health.

To gain insight into these impacts, Wellenius collaborated with Google on two studies and analyzed data from Google’s COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports to identify potential associations among social distancing policies, population mobility, and reduction in COVID-19 case trajectories in the US and Europe.

Published recently in the journals Nature Communications and PLOS ONE, the studies found that shelter-in-place mandates in US states and European countries were among the most effective policies in reducing the amount of time people spent away from their residences, while school closures, bans on large gatherings, and voluntary recommendations appeared to be the least effective approaches. The studies also showed that decreased population mobility led to substantial reductions in COVID case growth in the initial weeks of the pandemic.

Not all social distancing policies are equally effective at protecting people from COVID-19.

“Broadly, our findings showed that how much time people spend away from their residence is an important predictor of the risk of infection, and some restrictions and policies work better than others to encourage people to stay home,” says Wellenius. “In other words, not all social distancing policies are equally effective at protecting people from COVID-19.”

The collaboration, which also included researchers from Brown University School of Public Health and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, grew in part from conversations that sparked after Wellenius joined Google Research as a short-term visiting research scientist in January 2020. The team soon launched the COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports as a way for Google to contribute to the global pandemic response and provide public health experts with data that could aid COVID research and decision-making.

“At the start of the pandemic, Google heard from researchers that mobility data could be useful in better understanding the spread of the virus, so our team quickly worked to generate the Community Mobility Reports to help people better understand the impacts of policies such as shelter-in-place and social distancing,” says Evgeniy Gabrilovich, principal research scientist and research director at Google Health, and corresponding author of both studies. “We partnered closely with Professor Wellenius on a range of projects, and his expertise on public and environmental health was instrumental in advising the development of Alphabet’s Community Mobility Reports, as well as the COVID-19 symptom search trends dataset.”

The reports use aggregated, anonymized data from users who have opted in to the service (similar to the way Google Maps displays businesses’ popular times), and chart mobility trends to provide insight on how people’s movements changed over time as government policies evolved during the pandemic.

The data processing involves advanced differential privacy techniques to ensure that users’ personal information is not disclosed or compromised—an approach which earned Google and the research team a recent nod from the Future of Privacy Forum, as one of two recipients of the data privacy think tank’s second-annual FPF Award for Research Data Stewardship. The award highlights partnerships between companies and academics which demonstrate novel best practices and approaches to sharing corporate data in order to advance scientific knowledge.

“The FPF Award for Research Data Stewardship recognizes the extraordinary efforts of the dedicated team at Google,” says Wellenius. “I count myself very fortunate to have had the opportunity to collaborate with the team.”

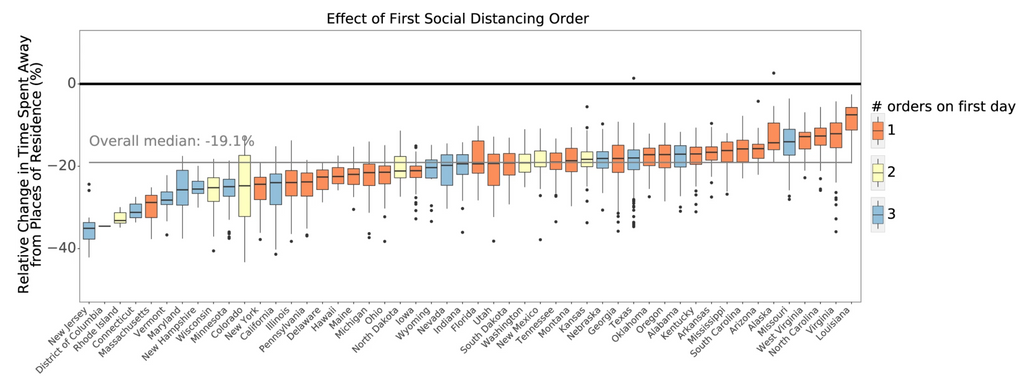

In the Nature Communications study, the researchers found that state-of-emergency declarations resulted in a 10 percent reduction in time spent away from places of residence. The implementation of one or more physical distancing policies resulted in an additional 25 percent reduction, and subsequent shelter-in-place mandates led to an additional 29 percent reduction in the time that people spent away from their homes. The study also found that a 10 percent decrease in mobility was associated with 17.5 percent fewer new COVID-19 cases reported 2 weeks later.

“In the US, the single most effective social distancing policy seemed to be the mandatory limits on bar and restaurant operations,” says Wellenius, while bans on large gatherings “just might not make that much of a difference.” One explanation for this outcome could be that closing bars and restaurants effectively limits traffic to other businesses, he says. “People don’t typically just do one thing when they are out—they do a number of things, such as going to lunch, and then going shopping. So if you remove the dining option, it may become much less appealing to go out and do a number of things.”

Wellenius cautions that this study was conducted using data from the initial wave of the COVID-19 pandemic and before the evidence of face coverings as protective measures prompted mask mandates, so these findings could change in the presence of masks—but nonetheless, quantifying the effects of these policies provides valuable information for future epidemiologic and policy work.

“The important thing is that now we can estimate what the impact would be on case growth if we get people to stay home by a specific amount of time—such as 10 percent or 20 percent more,” says Wellenius. “If people stay home, we know there is less opportunity for contagion—which is self-evident now, but wasn’t so obvious at the start of the pandemic. Being able to measure the effects of state-level mandates can help inform the next pandemic response by incorporating the benefits of social distancing policies into forecast models.”

Although the populations, environments, and government policies by European leaders varied significantly across the countries and in comparison to the US state-level measures, the researchers concluded similar findings to the US analysis: mandatory shelter-in-place orders among 27 European countries yielded the largest decrease in mobility—at an average of 16.7 percent—followed by mandatory workplace closures. Detailed in the PLOS ONE study, large gathering bans also appeared to yield the least effect on changes in mobility, resulting in only a 7.8 percent reduction in people being out and about. The researchers observed significant differences in decreased mobility across the countries though. For example, there was a 70 percent decrease in time spent away from places of residence in Spain, versus a 20 percent decrease in Sweden.

Quantifying this relationship between mandatory or voluntary social distancing policies and a reduction in mobility allowed the researchers to test certain assumptions made early in the pandemic, says Liana Rosenkrantz Woskie, lead author of the PLOS ONE study and a research fellow at the Harvard Chan School.

“In Sweden, the government justified a low-touch mobility recommendation instead of a lockdown, appealing to shared community responsibility,” says Woskie. “However, in our work we found people in Sweden moved around more than any other EU country we examined, which corresponded with higher COVID-19 case growth.

“Unfortunately, this suggests strategies that rely on public goodwill may not adequately mitigate pandemic risk,” she says.

Still, mandatory orders come with their own harm, she adds. “If we advocate mandatory measures in future pandemics, we need a commitment to comprehensive and consistent support for communities less able to adhere to strict guidelines, such as safe housing, food and medical support.”

The study findings also revealed that the link between decreases in mobility and COVID-19 cases two weeks later was somewhat weaker in Europe than it was in the US; while a 10 percent decrease in time spent away from residence was associated with a 17.5 percent reduction in case growth two weeks later in the US, it was only associated with an 11.8 percent reduction in case growth in Europe.

But the two studies are notably different, since policy differences between states were compared in the US study while policy differences between countries were compared across Europe. Federal public health recommendations in the US that promoted social distancing in addition to state mandates may explain the differences in decreased case growth in the US versus Europe, says Thomas Tsai, co-author of both studies and an assistant professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Harvard Chan School.

“In the US, we were able to exploit state-level variations in social distancing policies as a natural experiment, but there was still the national context of public health guidance and media coverage that may have contributed to the slightly greater effect on reduction of COVID-19 cases with changes in mobility,” Tsai says. “For Europe, we focused on national-level analyses between countries, and there could have been significant variation at the sub-national level within countries.”

Tsai also notes that the rise in COVID-19 cases began slightly earlier in Europe than in the US, so the association between mobility changes and COVID-19 case growth could vary based on when in the course of the pandemic social distancing measures were enacted. Population density and other characteristics of where and how people live also differ greatly between the US and Europe, potentially contributing to the observed differences.

“These studies demonstrate the power of collaboration between a technology company such as Google and academic partners at leading institutions such as Harvard, Brown, and Boston University,” says Wellenius. “I believe we are in a new era where such partnerships will prove instrumental to advancing public health.”