Towards Greater Inclusion in a Diverse Community.

Co-authored by Dean Yvette Cozier

Co-authored by Dean Yvette Cozier

Today’s note follows what we hope was a happy and restful Thanksgiving for all. In the spirit of the holiday, we have been reflecting on the reasons we, collectively, have to give thanks, even as we navigate a difficult political and cultural moment. It is worth noting that Thanksgiving was established as a federal holiday in 1863, during a far more tumultuous era than our own. That the nation chose, in the midst of the Civil War, to pause for a day of gratitude, suggests how crisis can clarify the many ways we remain truly fortunate. For an example of this good fortune, we need only look to the vibrant school community we are privileged to call ours, one that is committed to an ideal of diversity and inclusion. We have written previously about the importance of diversity and inclusion in public health. Today, we will revisit this topic, with special emphasis on how we can achieve greater inclusion in a diverse community, thankful for the chance to continually improve how we express our values as a school.

Diversity is indeed a core SPH value, enriching our community on multiple levels. It is no accident that, in statements central to our institutional identity, diversity emerges as a key theme—from our Strategic Thinking Report, to our Diversity and Inclusion Statement, to our Values Statement where we commit to creating “a respectful, collaborative, diverse, and inclusive community within SPH.” Diversity is also at the heart of public health. Working to improve the health of populations means partnering with a broad range of constituencies, doing so in a respectful, receptive, inclusive manner. This work is especially critical at our current political moment. As societies around the world become more heterogeneous, we have seen how this change can provoke backlash. It has become clear that successfully navigating these cultural shifts, with empathy and a willingness to care for our neighbors, will be perhaps the sentinel challenge of the 21st century.

At SPH, we strive to meet this challenge by promoting diversity through events, discussion, and our efforts to develop pipeline programs that will help us attract more underrepresented students. We do this to ensure that all have the opportunity to engage in the work of population health, and in order to maintain a school that is as diverse as the world around it. However, diversity is insufficient unless it is accompanied by inclusion. This means building a community that both welcomes people with different perspectives and also makes sure that they can participate fully in the life of our school. For this reason, in 2015, we created an 11-point plan to inform a culture of inclusion at SPH. Using the plan as a guide, we have taken a number of steps to ensure a more inclusive institution. We have created affinity groups where members of our community can discuss issues of diversity and inclusion, perform community service, and sponsor cultural events. We have also pursued a more inclusive classroom through a range of workshops designed to help faculty lead constructive discussions about challenging topics such as race, class, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Finally—recognizing the power of words to shape community—we have worked to foster a language of inclusion at our school, by emphasizing, for example, the use of preferred gender pronouns (PGP), so that what we say might better reflect the experience of our gender-non-conforming peers.

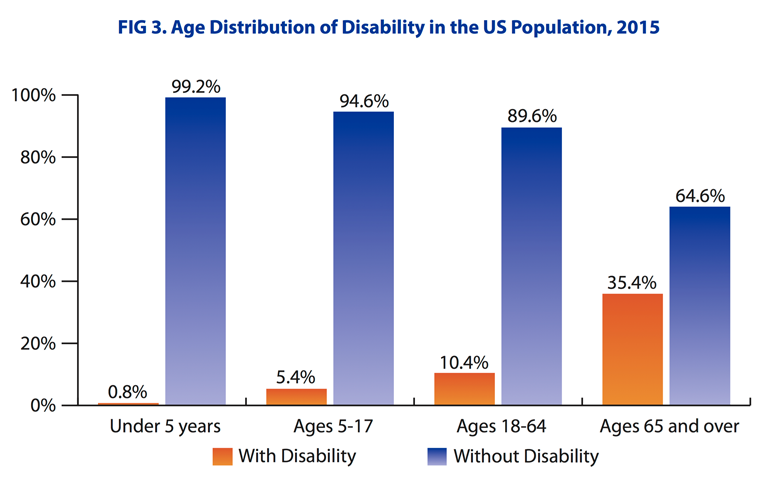

Yet moving towards greater diversity and inclusion is a task that is never finished. It is a process that invites constant reflection and improvement. In this spirit, we have, in recent months, come to reflect on an area where we, as a school, can do better. There are several groups that we do not talk about as often as we might when we talk about diversity, and this can translate into a lack of inclusion. One such group is adults with disabilities. This, in some ways, mirrors public health’s broader slowness to fully address the needs of populations with disabilities, an especially striking oversight given the size of this population. According to the WHO, more than 1 billion people experience some form of disability worldwide. In the US, nearly 13 percent of the population had a disability in 2015. The large percentage of Americans with disabilities reflects, in part, population aging. In 2015, about 1 percent of the under-5 population had a disability. This figure rose to about 5 percent of the 5 to 17 population, about 10 percent of the 18 to 64 population, and about 35 percent of the 65 and older population (Figure 1).

Kraus L. 2016 Disability Statistics Annual Report. Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire; 2017.

The American Community Survey identifies six types of disability: vision, hearing, cognitive, ambulatory, self-care, and independent living; the intersection of these disabilities is, in and of itself, an important focus for us in public health. Adults with disabilities are four times likelier than adults without disabilities to say that their health is in fair or poor condition. They also face their own unique health challenges, ranging from physical complications arising as a consequence of their disability or the underlying cause of it, to barriers to healthcare access. In the US, for example, adults who have been deaf from birth or early childhood are less likely to have visited a physician than other patients. Populations facing cognitive disabilities also face unique challenges. Because their disability is less visible, they can find themselves marginalized by a world that does not always view physical and cognitive conditions (i.e., learning differences) as equally valid concerns. Mental health conditions are also invisible. Addressing mental health as a public health priority will remain at the center of our school’s mission, as we work to become ever better at reaching out to students facing cognitive challenges, both common and severe, such as depression, schizophrenia, ADHD, dyslexia, dyscalculia, and learning disabilities.

Diversity means that we invite everyone to the table; inclusion means that we empower everyone at the table to participate in the conversation. With this in mind, we are working to make SPH the most inclusive school on multiple axes, leading with our commitment to be more receptive to students with disabilities, recognizing that we are imperfect and aiming to improve at all times. In addition to our current work of providing support services to students, efforts are already underway to make our physical and visual space more navigable for them, with improved accessibility in all our educational spaces. We are also working to provide captioning for videos used in our classrooms, and ASL interpretation at our Signature Programs. Thinking ahead, we are beginning the planning process for a Diversity and Inclusion event organized around the theme of disability, to explore the experiences and challenges of disabled populations. Through such events, and continued school-wide conversation, we aim to deepen our engagement with inclusion, so that every opportunity we offer is accessible to all members of our community, without exception.

We hope everyone had a terrific Thanksgiving week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro and Yvette

Yvette C. Cozier, BA, MPH, DSc,

Assistant Dean for Diversity and Inclusion

Associate Professor, Epidemiology

Boston University School of Public Health

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: We are grateful to Eric DelGizzo and Professors Rani Elwy and David Sherr for their contributions to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/