On Economic Justice.

Before I begin today’s Note, an acknowledgment of the events of last week. Since assuming office, President Trump has taken a number of steps that pose a threat to the health of populations. These include reinstating and expanding the “Global Gag Rule,” also known as “the Mexico City Policy”—which will curtail the ability of women worldwide to access safe reproductive care—as well as moving to roll back environmental regulations, limit immigration from several predominantly Muslim countries, and lay the groundwork for the construction of a wall along our southern border. I have written before about how reproductive justice, environmental stewardship, and the health of migrants and refugees are all key public health concerns. For added context about the issue of migrant health, we have chosen to re-run a prior Dean’s Note on the subject. The content of today’s Note suggests a way forward; a possible strategy to help us navigate this uncertain new terrain. These recent events may justifiably provoke anxiety. They also argue all the more, I think, for the essential role of science, scholarship, and a robust academic engagement in the critical issues of our time that shape the public’s health.

Before I begin today’s Note, an acknowledgment of the events of last week. Since assuming office, President Trump has taken a number of steps that pose a threat to the health of populations. These include reinstating and expanding the “Global Gag Rule,” also known as “the Mexico City Policy”—which will curtail the ability of women worldwide to access safe reproductive care—as well as moving to roll back environmental regulations, limit immigration from several predominantly Muslim countries, and lay the groundwork for the construction of a wall along our southern border. I have written before about how reproductive justice, environmental stewardship, and the health of migrants and refugees are all key public health concerns. For added context about the issue of migrant health, we have chosen to re-run a prior Dean’s Note on the subject. The content of today’s Note suggests a way forward; a possible strategy to help us navigate this uncertain new terrain. These recent events may justifiably provoke anxiety. They also argue all the more, I think, for the essential role of science, scholarship, and a robust academic engagement in the critical issues of our time that shape the public’s health.

On to today’s Note. In honor of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, we recently re-ran a previous Dean’s Note on social justice as a foundational concern of public health. I continue to think that social justice and public health are inseparable concerns. In the aftermath of the election, however, I have found myself thinking harder about the very concept of social justice, and wondering whether within the broader idea we cannot sharpen the aspects of social justice we should be advocating for in public health. President Trump’s electoral win was, in no small part, a result of the frustration of a predominantly white working class, a frustration that, while also culturally rooted, is fundamentally driven by economic challenges faced by large parts of the country. Paradoxically, Trump’s platform included essentially no concrete efforts to address some of the economic challenges that resulted in his election. This would suggest that some much more fundamental frustration elected Trump—the hope of a change, any change. It seems to me that the expression of this impulse was largely a plea for economic justice.

What might we mean by “economic justice”?

Economic justice has been defined as “a set of moral principles for building economic institutions, the ultimate goal of which is to create an opportunity for each person to create a sufficient material foundation upon which to have a dignified, productive, and creative life beyond economics.” Therefore, an economic justice argument focuses on the need to ensure that everyone has access to the material resources that create opportunities, in order to live a life unencumbered by pressing economic concerns. Definitionally, this recalls the broader view of health expressed by the World Health Organization: “A state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” In both cases, the pursuit of health and economic justice aspires to something greater than simply physical well-being or financial solvency. The goal is, rather, to shape the fundamental conditions—i.e. higher incomes, or freedom from preventable disease—that allow people to live fulfilling, sustainable lives free from concerns about meeting basic needs, or about falling into poor health.

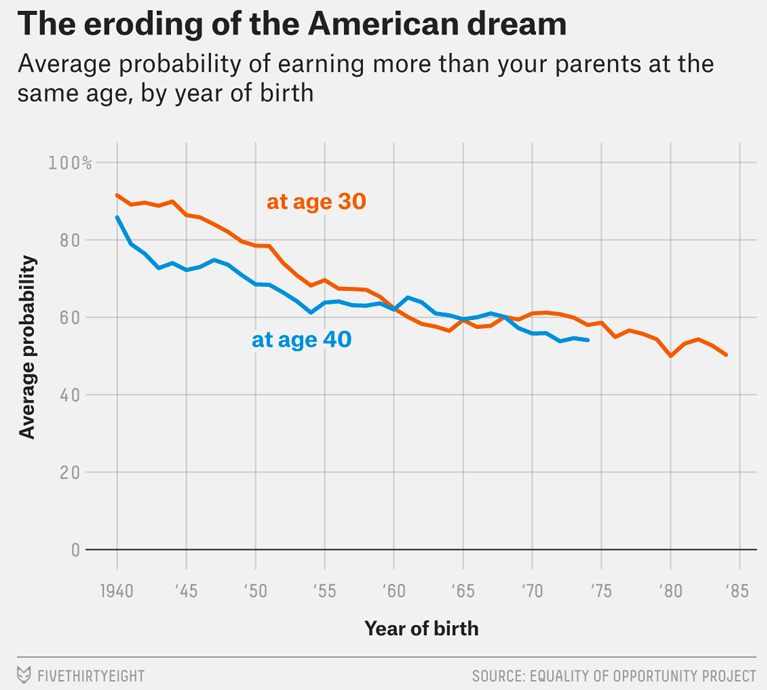

We are currently quite far from having widespread economic justice across the country; in fact, we are drifting further and further away from it. A simple look at what has happened to incomes in the US makes the point well. From the end of World War II until the 1970s, our economy grew, and broad segments of the population shared in this prosperity. Since then, however, income for the middle and lower levels of the wealth distribution has declined, while income at the top has grown at a dramatic rate. According to the US Congressional Budget Office, the aggregate family wealth in this country was $67 trillion in 2013. At the time, families in the top 10 percent of the wealth distribution controlled 76 percent of this wealth. This is a significant increase from 1989, when families in the top 10 percent controlled 67 percent of the nation’s family wealth. Meanwhile, the share of the wealth controlled by families in the bottom half of the country’s wealth distribution declined during that period from 3 percent to 1 percent. As wealth becomes more entrenched, the country has seen a general decline in social mobility, despite our national, Horatio Alger-inspired myth of pulling oneself up “by the bootstraps.” In 1970, about 9 in 10 30-year-olds earned more money than their parents did at that age. In 2014, however, only 5 in 10 30-year-olds could report that same intergenerational progress (Figure 1).

Casselman B. Inequality is Killing the American Dream. FiveThirtyEight. December 8, 2016. http://fivethirtyeight.com/features/inequality-is-killing-the-american-dream/?ex_cid=538twitter Accessed January 5, 2016.

This mobility decline has been particularly pronounced in the Rust Belt states that Trump carried in the election. Indeed, it is worth recalling that, in his speech announcing his candidacy, Trump spoke to this decline, saying “[T]he American dream is dead.”

Although there is a robust academic debate about the exact architecture of the income and health relationship, there is little doubt that economics fundamentally drive a broad range of factors, including health. This would suggest that a focus on economic factors as foundational to the production of health stands to be both a rational investment in the drivers of population health and well-being, and, potentially, a focus for collective efforts towards creating a better world. Unfortunately, efforts to tackle income and economic drivers often get tangled in ideological discussions, in clashes around visions for an economy that is driven principally by individual efforts versus government investment. In some respects, this argument, while perhaps relevant at a political level, stymies efforts to improve our foundational economic function towards the end of creating healthier populations.

I would suggest, therefore, that an economic justice focus stands to lend clarity to our efforts and can serve as a focus for the work of those concerned with the health of populations and with the well-being of populations more broadly.

How might a focus on economic justice inform our collective aspirations?

There are several current efforts animating the public debate that could be seen as approaches to achieve economic justice, and that could, with such a focus, rise to the top of our agenda. Perhaps the most direct of these is the universal basic income (UBI), a regular, guaranteed payment made to each citizen, regardless of employment or economic status. Although ideological resistance to government welfare has made widespread UBI implementation controversial, the idea has been gaining traction, with countries beginning to research how the concept might work in practice. Finland, for example, has just become the first country in recent years to conduct a national experiment based on the idea, giving a cohort of 2,000 citizens a guaranteed income. While some may object to UBI implementation, and welfare more broadly, ostensibly because they reward laziness, it is important to note that it is quite possible in today’s economy to work hard and have very little to show for it, just as it is not uncommon for wealthy individuals to remain so without having to work themselves. At core, the UBI debate is about fairness; about whether we want to build a society that alleviates economic injustice or entrenches it. While our present political moment makes a UBI solution unlikely, there are other steps that can indeed get us closer to economic justice, even in our federal context. Extending coverage of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and reforming the federal estate tax to minimize loopholes, diverting funds currently concentrated at the top of the wealth distribution toward the public good, would get us closer to the goals of economic justice.

There are a number of challenges to the kind of political engagement necessary to mitigate economic injustice in the US. This engagement entails the often frustrating business of working within systems to effect change. It also opens us to charges of partisanship. But health is inherently political, and while the incoming Trump administration is in many ways a discouraging prospect for public health, it also represents an unprecedented opportunity to argue for lasting solutions to the problem of economic injustice, towards healthier populations.

In next week’s note, I will discuss at greater length how a call for shared justice, coupled with this approach to economic justice, might even further advance the cause of public health.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor, Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Eric DelGizzo and Catherine Ettman for their contributions to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/