Health and the City.

Before I delve into the topic of this week’s Dean’s Note, I want to acknowledge that today, March 8, is International Women’s Day—a reminder to all of us of the importance of eliminating gender disparities in primary and secondary education worldwide and of supporting women in leadership. Girls’ education is critically linked to self-determination, improved social and economic status, and positive health outcomes. Maternal deaths and pregnancy-related problems cannot be eliminated without the empowerment of women, which entails better access to health information and care and control of resources. I will write more on this topic in a future Dean’s Note.

Before I delve into the topic of this week’s Dean’s Note, I want to acknowledge that today, March 8, is International Women’s Day—a reminder to all of us of the importance of eliminating gender disparities in primary and secondary education worldwide and of supporting women in leadership. Girls’ education is critically linked to self-determination, improved social and economic status, and positive health outcomes. Maternal deaths and pregnancy-related problems cannot be eliminated without the empowerment of women, which entails better access to health information and care and control of resources. I will write more on this topic in a future Dean’s Note.

Health and the City

Urbanization is one of the two most important global demographic shifts over the past 200 years, with the other being the aging of populations. The demographic evidence for urbanization is unquestionable. In 2014, about 54 percent of the world’s population was living in urban areas, compared to only 35 percent in 1960 and 5 percent in 1800. Just since 2000, more than 1 billion people have been added to urban areas, raising the proportion of urban dwellers to more than 80 percent in 64 different countries. By 2010, there was roughly the same number of people living in urban areas as there were in the entire world in 1950. Defying conventional and perhaps media-driven images of cities and urban dwellers, the most rapidly growing cities today are in low- and middle-income countries. The two cities with the highest average annual growth rate between 2006 and 2020 are expected to be Beihai in southern China and Ghaziabad in India, with other fast-growing cities in Nigeria, Mali, and Bangladesh. Although cross-country heterogeneity in what constitute city boundaries makes such definitions challenging, the world’s largest cities today probably are Karachi, Shanghai, Mumbai, Beijing, and Delhi, with New York City being one of the world’s largest metropolitan areas.

Urban Health

As urbanization accelerated, the field of urban health emerged around the turn of the 21st century, concerned with understanding how, and why, cities influence health. An appreciation of the role that cities can play in shaping the health of populations is an extension of a growing scholarship around the role of context as an inextricable determinant of the health of populations, the subject of one of my previous Dean’s Notes. In many respects, that cities influence health is intuitive. Cities influence the food we eat, the water we drink, and the air we breathe. Urban living can affect everything from available food to walkability to the spread of infectious diseases. Early writing in the field was focused on challenges to the health of populations in cities, including the coining of the term “urban health penalty.” However, as the field has matured, it has become readily apparent that the relationship between urban environments and health is complex, and that a range of determinants of health, both positive and negative, characterizes the urban experience. In the past decades, an equally apparent “urban health advantage” has emerged where, particularly in high-income countries, overall health in urban areas surpasses that of non-urban areas.

The Determinants of Health in Cities

In an effort to rationalize the full set of determinants of health within urban environments, we suggested that three particular factors be considered as drivers of health in cities: the physical environment, the social environment, and access to health and social services. Examples of how these factors influence health abound in the literature. Among the most studied is the physical environment. One recent Boston-based study found a link between traffic-related air pollutants and impaired glucose tolerance during pregnancy. The World Health Organization recently linked 7 million premature deaths globally to air pollution. Brian Saelens and colleagues found that children in Seattle and San Diego who live in neighborhoods with more access to healthy foods and a better “physical activity environment” were less likely to be obese after adjusting for individual, family, and neighborhood-level demographics. With respect to the social environment, Mahasin Mujahid and colleagues found that residents of neighborhoods with higher social cohesion were less likely to have hypertension. Less studied is the urban service environment, though some have focused on access to services among urban subgroups such as immigrants and homeless youth. One study found that low-income and racial minority communities in Los Angeles had limited access to integrated mental health care in LA County. Studies concerned with studying these factors and bringing to light how we may best inflect them to the end of creating healthier cities are today burgeoning. Urban health has readily become transdisciplinary, and researchers are capitalizing on new technology and big data that aim to get to the bottom of the drivers of health in cities, both domestic and global.

Health and Boston

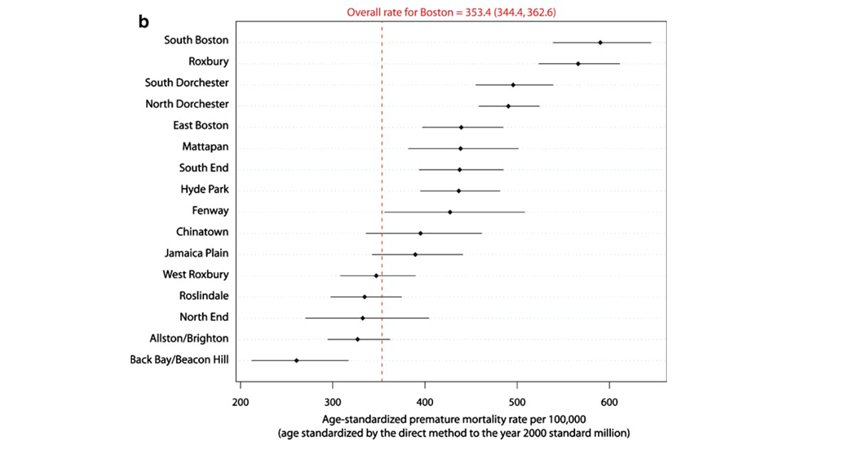

Perhaps the abstraction of “urban health” is brought home more acutely when one considers our home, Boston. Boston is characterized by dramatic heterogeneity in health across the city. Life expectancy in this relatively small city varies by as much as 33 years between neighborhoods that are only a couple of miles away from each other, with a high of 91.9 in Back Bay and a low of 58.9 in Roxbury. Comparably, Jarvis Chen and colleagues compared premature mortality rates across neighborhoods in Boston, finding that Roxbury and South Boston had by far the highest rates and Back Bay/Beacon hill had the lowest (see figure).

How do urban characteristics in Boston shape the health of the populations who live here? A spatial study by Dustin Duncan and colleagues compared open recreational space to neighborhood characteristics and found that neighborhoods with a high proportion of non-Hispanic black residents had significantly less open space, increasing risk of obesity due to lack of physical activity. Another study focused on physical activity used the 2008 Boston Youth Survey to show a relationship between high social fragmentation in a neighborhood and lower physical activity among adolescents. Consistent with research in other cities, study after study show that many of the indictors that are associated with poor health cluster together. The lowest-income neighborhoods in Boston coincide with those that have less open green space and worse health outcomes. In many studies, area-level poverty serves as a ready marker for the accumulation of factors that adversely affect health in urban areas. In the aforementioned Boston study, Chen and colleagues found that the incidence of premature mortality rates was 1.4 times higher in the most economically deprived census tracts compared to those in the least impoverished tracts. They also found an attributable fraction of 25 percent to 30 percent excess deaths due to living in high-poverty census tracts. These census tracts with the highest poverty have also consistently been found to have the highest proportion of black residents and the lowest levels of education.

Opportunities in Urban Health

In many respects, the study of health in cities presents a tremendous opportunity, both for a multi-level understanding of population health and for our urban school of public health to find a focus for scholarship and action. Clearly, factors at the political, structural, social, and service delivery level are jointly responsible for the health of urban residents, and an understanding of the dynamics that knit together this causal web presents opportunities for both knowledge and, potentially, intervention. There is growing momentum towards building movements that aspire to healthier cities, with emerging municipal efforts that aim to capitalize on the growing political latitude that cities are enjoying towards the development of innovative approaches to promote urban health. This strikes me as presenting us, in the academy, with an opportunity to marry multiple strands of the core mission of academic public health. Scholarship that aims to understand how cities influence health, and how the urban environment gets under the skin, can be interesting, formative, and productive. Our students overwhelmingly come from, and will overwhelmingly work in, urban areas, presenting an opportunity for grounding of our scholarship and educational experience in our students’ salient present. And, urban environments present translational opportunities that can, through partnerships with colleagues in practice, contribute to opportunities to improve the health of populations, and allow us to do well by doing good.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Professor, Boston University School of Public Health

@sandrogalea