Smarter Gun Legislation through Data.

The nation’s patchwork of firearm legislation provides a kind of natural experiment for researchers looking for ways to effectively prevent gun deaths and injuries—but there is a catch. “There are many exemptions and nuances of firearm laws, so what one person means by a particular type of law could be totally different than what someone else means,” says Michael Siegel, professor of community health sciences. How to know if universal background checks work if the definition is anything but universal?

The nation’s patchwork of firearm legislation provides a kind of natural experiment for researchers looking for ways to effectively prevent gun deaths and injuries—but there is a catch. “There are many exemptions and nuances of firearm laws, so what one person means by a particular type of law could be totally different than what someone else means,” says Michael Siegel, professor of community health sciences. How to know if universal background checks work if the definition is anything but universal?

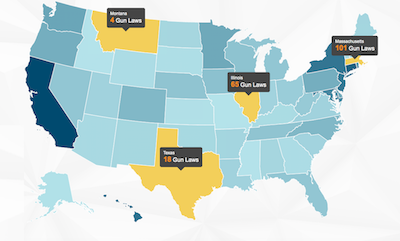

To help researchers evaluate the actual content and enforcement of laws, rather than just what the laws appear to be, Siegel and his colleagues created the State Firearm Laws Database. Funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Evidence for Action Program, the database includes all state firearm legislation back to 1991, and is constantly updated as states add—and subtract—gun laws. Every provision of every law is carefully coded so that researchers don’t find themselves comparing apples to oranges.

For example, Siegel says, both California and Arizona have laws prohibiting the sale of ammunition to minors. But Arizona has an exemption: “It is not a crime in Arizona to sell ammunition to a minor as long as they have a note giving them parental permission,” Siegel says. So, in the database, California is coded as really having a ban on selling ammunition to minors, but Arizona is not. That way, researchers can see what happens when minors can never buy ammunition, when they can buy ammunition with parental permission, and when they don’t need permission at all.

“This database came at an important time, as the views of the public are both changing and polarizing on the issue of gun violence,” says Molly Pahn (SPH’15), who did much of the work of compiling the state law data as a research assistant after completing her master’s in public health. Pahn had been a political science major as an undergraduate, interned at the state legislature in Tennessee, and had experience researching legislation with the Westlaw database. She is also from Memphis, a city that has had one of the highest gun-violence rates in America for as long as she can remember, Pahn says, motivating her to work on firearm legislation at SPH and now as a law student back home.

Ziming Xuan, associate professor of community health sciences and co-investigator on the team, says that the growing momentum for something to be done about the gun violence epidemic, exemplified by the March for Our Lives movement, is heartening. But National Rifle Association-backed federal laws limited gun research for decades, so it is still a challenge to identify which policies will actually save lives. That is where the State Firearm Laws Database comes in. “It helps align concerted efforts to focus on advocacy for several key, effective policies, rather than diverting resources on actions that are not necessarily effective in reducing gun violence,” he says.

This year, Siegel, Xuan, Pahn, and their colleagues published the first study to directly compare the association between state-level homicide rates and a set of state gun laws in one statistical model, thanks to the database. The takeaway, Siegel says: “Public health advocates should prioritize policies designed to keep guns out of the hands of people who are at a high risk of violence based on their criminal history.”

There are many other studies ongoing, and much to tease out, including the fact that the effectiveness of gun laws in a state is limited by the flow of guns from nearby states with lax laws—another Firearm State Laws Database finding. But the work will pay off, the three researchers agree. Says Pahn, “If just one life is saved, it will be worthwhile.”