The Growing Impact of Dementia on the Health of Populations.

An update, before today’s note. Looking ahead to next week, we have a number of events planned that will allow us to engage with issues core to the health of populations. On Monday, April 10, we will host a Dean’s Seminar on income inequality and health in America, a subject I have written about before in these notes. At our Wednesday, April 12, Public Health Forum, we will welcome Mary Sano, director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, who will discuss dementia—the subject of today’s note—and how we can mitigate dementia and memory loss as we age. Finally, on Thursday, April 13, we will host a Dean’s Seminar on the ongoing fight for transgender equity. The discussion will be led by Mason Dunn, executive director of the Massachusetts Transgender Political Coalition. With the Trump administration’s rollback of Obama-era transgender protections, this subject has taken on, I think, a new urgency, even as the efforts of individuals and groups to oppose these measures inspire new hope.

An update, before today’s note. Looking ahead to next week, we have a number of events planned that will allow us to engage with issues core to the health of populations. On Monday, April 10, we will host a Dean’s Seminar on income inequality and health in America, a subject I have written about before in these notes. At our Wednesday, April 12, Public Health Forum, we will welcome Mary Sano, director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, who will discuss dementia—the subject of today’s note—and how we can mitigate dementia and memory loss as we age. Finally, on Thursday, April 13, we will host a Dean’s Seminar on the ongoing fight for transgender equity. The discussion will be led by Mason Dunn, executive director of the Massachusetts Transgender Political Coalition. With the Trump administration’s rollback of Obama-era transgender protections, this subject has taken on, I think, a new urgency, even as the efforts of individuals and groups to oppose these measures inspire new hope.

On to today’s note. In 1907, Alois Alzheimer became the first physician to describe the clinical and neurological effects associated with dementia. His research was driven by his inability to prevent the inexplicable deterioration of one of his patients over the course of six years. Sadly, if the same patient were alive today, she would most likely face the same outcome. A reflection, then, on the persistent and growing impact of dementia as a leading challenge to the health of populations in this generation.

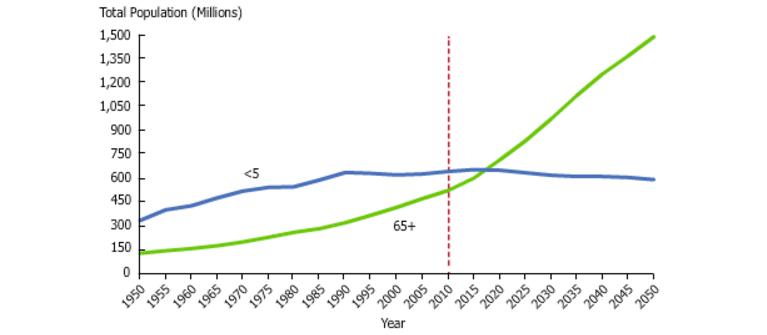

The world’s population is aging; the Population Reference Bureau projects that, in 2050, there will be 2.5 times as many people aged 65-plus as children under 5 years of age. This shift in demographics can be linked to increasing human longevity, declining birth rates in low income countries, and very low birth rates in high income countries. This trend has also been shaped by a post-World War II baby boom in certain countries (e.g., the US, Canada, Japan, Australia), at least for the period between 2010 and about 2035.

There is no question that human longevity is a triumph for public health. However, as the population grows older, we face new challenges. I previously addressed some of the challenges and opportunities associated with an aging population in a Dean’s Note on the role of population health in the era of global aging. Today, I want to address one particular challenge we face as populations age: dementia, and the seemingly inevitable worldwide increase in persons with dementia that accompanies the global aging population (Figure 1).

World Population Aging. National Institute on Aging Web site. https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/dbsr/global-aging Accessed April 4, 2017.

To frame the scope of the issue: disability accounts for 23 percent of the global burden of disease in older adults, and dementia is a major contributor to that burden. A new case of dementia is diagnosed every four seconds. Dementia is the leading cause of dependency and disability among the elderly. Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) attributed to dementia are expected to rise 82.6 percent between 2004 and 2030. In 2015, there were 47 million people living with dementia worldwide, and the number is expected to double every 20 years, reaching 131.5 million in 2050. The increase will mainly occur in low- and middle-income countries (Figure 2).

Dementia statistics. Alzheimer’s Disease International Web site. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/statistics Accessed April 4, 2017.

Dementia is a syndrome characterized by deterioration in memory and other cognitive functions, such as reasoning, which diminishes an individual’s ability to perform daily activities. It is important to distinguish dementia, the syndrome of deteriorating memory, from the pathologic causes of dementia. The pathology manifests itself as dementia; as the pathology worsens, so does the dementia. Although the risk of developing dementia increases with advancing age, dementia is not part of the normal aging process. About 40 percent of people over the age of 65 experience short-term forgetfulness; our brains, like our bodies, slow down with normal aging, leading to occasional memory lapses. Dementia, however, involves severe decline in mental ability that disrupts daily function.

There are a number of conditions, including vascular disorders and brain trauma, that lead to dementia. Alzheimer’s disease accounts for 60 percent to 80 percent of dementia cases worldwide, although maybe half of dementia cases involve mixed pathology, usually Alzheimer’s combined with a different pathology. In addition to age, risk factors for dementia include family history, Down syndrome, depression, diabetes, and smoking. There is no specific prognosis for dementia; the condition progresses quickly in some, while taking many years to advance in others. Moreover, life expectancy varies from one individual to another. Most people live an average of 4.5 years following a dementia diagnosis, with median survival in one review ranging from three to seven years; those diagnosed before the age of 70 are more likely to live for a decade or more. A person suffering from dementia might experience very severe memory loss, difficulty communicating, and loss of mobility. These symptoms can lead to further medical complications like pneumonia, weight loss, and inability to care for oneself. Effects of dementia are not limited to the individual, and extend to their families and caregivers. During later stages of dementia, taking care of afflicted individuals becomes an increasingly difficult task. Families and caregivers can experience guilt, grief and loss, anger, and disturbance of daily activities.

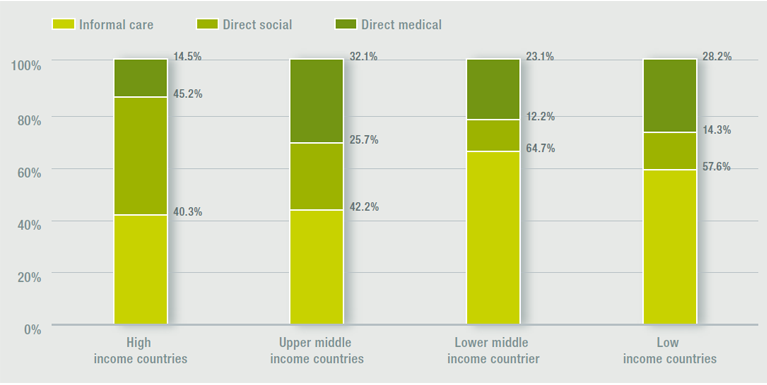

Dementia has pervasive societal consequences. The costs of caring for people with dementia are high, frequently driven by the need to provide a supportive environment at home or in care facilities. In 2014, caregivers spent $9.7 billion on daily care for family members with dementia worldwide. Other informal costs include the caregiver’s lost income, the value of caregiving time, and the caregiver’s excess health costs. I will discuss caregivers at greater length in a future note.

In 2008, the World Health Organization declared dementia a priority condition. In 2015, the worldwide cost of dementia was estimated to be $818 billion. If dementia care was a country, it would have the 18th largest economy in the world. The costs of dementia will continue to rise, reaching $1 trillion in 2018 and $2 trillion by 2030. Notably, medical costs constitute only a fraction of the overall costs of dementia. As Figure 3 illustrates, costs for informal care and direct social care make up most of the costs across the board in high- and low-income countries.

World Health Organization and Alzheimer’s Disease International. Dementia: a public health priority. 2012. Accessed at: http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/dementia_report_2012/en/

As the world population continues to age, research on dementia prevention is emerging as a focus area for public health. Interventions targeting foundational social structures that affect modifiable risk factors for dementia hold great potential for success. For example, Langa et al. linked some, but not all, of the decline in US dementia prevalence (11.6 percent in 2000 to 8.8 percent in 2012) to better educational attainment, control of cardiovascular risk factors, and better treatment for cardiovascular diseases. The reduction in prevalence has sparked further interest in investing in such interventions. Analysis of dementia-related research and expenditure suggests that policymakers, clinicians, and researchers must prioritize prevention and survival. Nonetheless, there is a limit to the impact of preventive interventions; regardless of the success level of preventive programs, some people will continue to live with dementia. Further, targeting risk factors does not necessarily translate to improving the quality of life for those already living with dementia. Short of research and interventions that address quality of life, the need for care and disability-related costs associated with dementia will continue to rise as the population continues to age. Yet cost reduction should not be the only incentive for us to prioritize quality of life. There is also an ethical argument for investing in these interventions; an adequate living standard and social protection is a right for all, including those living with dementia.

Consistent with much of my writing in these notes, I would argue that our mission should not be limited to advancing dementia prevention through research and interventions. The role of public health remains to continually advocate for building social and physical conditions that support individuals with dementia, towards a better quality of life for all.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful for the contributions of Salma Abdalla, MD, MPH and Professor Jennifer Weuve to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/