Lessons from Fire Prevention: Why We Can Head Off Disease Without Sacrificing Cure.

Public health is concerned with creating a healthier world, preferably one where we prevent disease before it starts. This inevitably occasions grappling with our overwhelming investment in medicine and curative care, and arguing for a recalibration of our investment towards the social, economic, and cultural factors that promote health. However, in making this case, it is important to remember that such an investment does not mean cutting back on doctors and hospitals. Prevention need not come at the expense of cure. I would like to illustrate this idea by way of an analogy: A look at the history of fire prevention in the US, and how we have been able to dramatically reduce the number of fires, while at the same time maintaining a robust network of firefighters, with prevention and cure working together to create a safer world.

Public health is concerned with creating a healthier world, preferably one where we prevent disease before it starts. This inevitably occasions grappling with our overwhelming investment in medicine and curative care, and arguing for a recalibration of our investment towards the social, economic, and cultural factors that promote health. However, in making this case, it is important to remember that such an investment does not mean cutting back on doctors and hospitals. Prevention need not come at the expense of cure. I would like to illustrate this idea by way of an analogy: A look at the history of fire prevention in the US, and how we have been able to dramatically reduce the number of fires, while at the same time maintaining a robust network of firefighters, with prevention and cure working together to create a safer world.

Firefighting traces its roots back to the Roman era. The traditional role of fire brigades, and, more recently, fire departments, has been to contain and extinguish fires when they start. Modern fire prevention is, in large part, a consequence of two tragedies that occurred on the same day in the latter half of the 19th century. On October 8th, 1871, both the Great Chicago Fire and the Wisconsin Peshtigo Fire broke out. The Great Chicago Fire took the lives of over 300 people, reduced 100,000 to homelessness, destroyed over 17,400 structures, and burned through over 2,000 acres. The Peshtigo Fire, which was the worst forest fire in American history, destroyed 16 towns and claimed over 1,000 lives. So catastrophic were these blazes, that they altered how fire safety was viewed in the US. Not long after the Great Fire, the city of Chicago began to commemorate the event with festivities. On the 40th anniversary of the Chicago Fire, the Fire Marshals Association of North America decided to formalize the anniversary, using it as an opportunity to promote fire prevention education. Since the early 1920s, Fire Prevention Week has been marked on the Sunday through Saturday period during which October 9 falls. The annual campaign typically has a theme related to fire prevention and emergency planning, such as having an emergency route worked out in case of fire. It would eventually become the longest running public health and safety observance on record. In 1920, President Woodrow Wilson issued the first National Fire Prevention Day proclamation. Calls for a prevention focus, with firefighters taking a leading role in these efforts, would circulate in the media during that decade, amplifying the call to stop fires before they start. On March 1, 1922, for example, Chief Daniel H. Shire wrote in Fire and Water Engineering, “Safeguarding a building against fire is today fire department work…you owe it to yourself and department by making your fire department both a prevention and an extinguishing unit.”

Over the years, fire prevention efforts, such as those espoused by Chief Shire, have taken hold and have made a clear difference, reducing deaths and injuries caused by fires. In 1977, there were 723,500 home fires in the US, with 5,865 civilian deaths and 21,640 injuries. In 2015, those numbers had been reduced to 365,500 home fires, with 2,650 civilian deaths and 11,075 injuries (Figure 1).

From: Home fires. National Fire Protection Association Web site. http://www.nfpa.org/news-and-research/fire-statistics-and-reports/fire-statistics/fires-by-property-type/residential/home-fires Accessed May 15, 2017.

On highways, vehicle fires have declined 64 percent during the period between 1980 and 2013, and building fires declined by 54 percent during that period. Prevention has also done much good in cities. New York City is a case in point. There, fire deaths reached their lowest level in a century last year, at 48 deaths—a significant decline from the city’s 1970 peak of 310 deaths. Why has fire prevention been so effective? One reason is likely that most fires are caused by correctable human error, or lack of safety systems such as sprinklers and smoke alarms. Unattended cooking, for example, contributes to one third of reported home cooking fires. And smoking materials led to fires that caused an average of 560 deaths between 2009 and 2013. This means that fire education, and taking simple preventive steps, such as smoke alarm installation, can make an enormous difference. The addition of smoke alarms can lower the risk of dying in a reported home fire by 50 percent. Fire education can help individuals and families avoid unsafe behavior, and encourage them to develop an escape plan in the event of fire.

The success of fire prevention is notable in that it has not come at the expense of the individuals and organizations tasked with fighting fires when they occur. In fact, as prevention has succeeded in reducing fires, the number of firefighters has actually increased. While there are 50 percent fewer home fires than there were just 30 years ago, there are approximately 50 percent more career firefighters, increasing from 237,750 in 1986 to 345,600 in 2015 (Figure 2).

From: Haynes JGH, Stein GP. US Fire Department Profile—2015. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association; 2017.

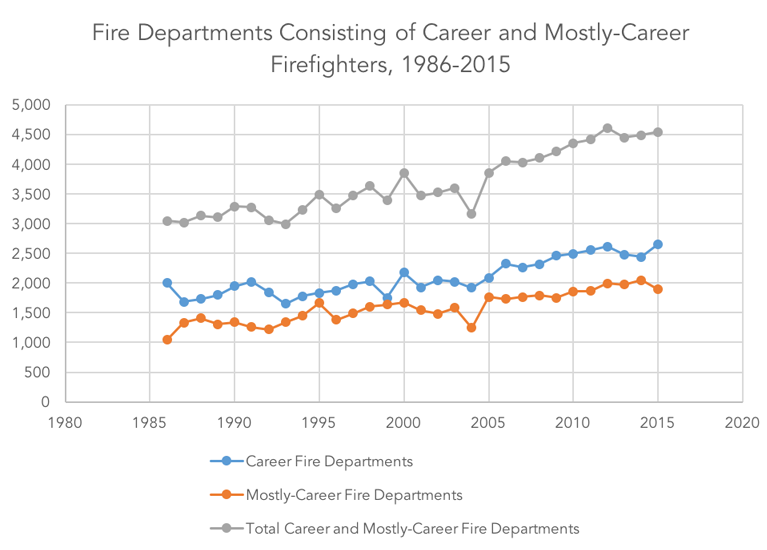

There has also been an increase in the number of fire departments consisting of career or mostly career firefighters in the US, from 3,043 in 1986 to 4,544 in 2015, representing an increase of 49.3 percent (Figure 3).

From: Haynes JGH, Stein GP. US Fire Department Profile—2015. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association; 2017.

Notably, governmental expenditures on local fire protection have also risen significantly during roughly this same time period. Adjusted for inflation, these expenditures have increased by 170 percent between 1980 and 2014, rising from $16.4 billion to $44.2 billion (Figure 4).

From: Haynes JGH, Stein GP. US Fire Department Profile—2015. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association; 2017.

It strikes me that the fundamental lesson here is that the rise of prevention does not necessitate the decline of cure. Through prevention we have been able to significantly reduce the number of people who are killed and injured by fires. At the same time, we have maintained a robust network of professional firefighters and fire departments geared towards fighting fires when they occur. Better still, local fire departments often play a leading role in promoting prevention, just as Chief Shire wanted, creating safer communities even as they stand ready to protect the public should the worst happen. We have cultivated this progress without coming anywhere near limiting the resources of these departments, as decade-by-decade spending increases have shown. At the moment, our investment in population health vs curative care does not reflect the balance between prevention and cure we see in this analogy. In the field of health, investment is, as we know, profoundly lopsided in favor of cure. But, importantly, a case for a greater focus on population health is not against an investment in cure. Rather, it is a call for creating a world where fewer “fires”—less disease—is better for all of us, even as we want to have the best possible firefighters to deal with fires when they happen, and the best possible cure to deal with disease when it happens. This reflects a vision of a world where we accord health the importance that we give it in our lives on both the prevention and cure side. I shall talk about the dividend that emerges from an investment in health in a future Dean’s Note.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Eric DelGizzo and Matthew Kim for their contributions to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/