Population Health in the Era of Global Aging.

When Frenchwoman Jeanne Calment was 90 years old, she sold her apartment to a lawyer named Andre-Francois Raffray on a contingency contract. The deal was that he would pay her 2,500 francs a month (about $400 at the time) until her death, whereupon the apartment would become his. This would have been a nice arrangement for Raffray, were it not for the fact that Calment lived for another 32 years, only to die at the age of 122—the longest human life on record. When she passed away, Raffray’s family was still paying for the apartment.

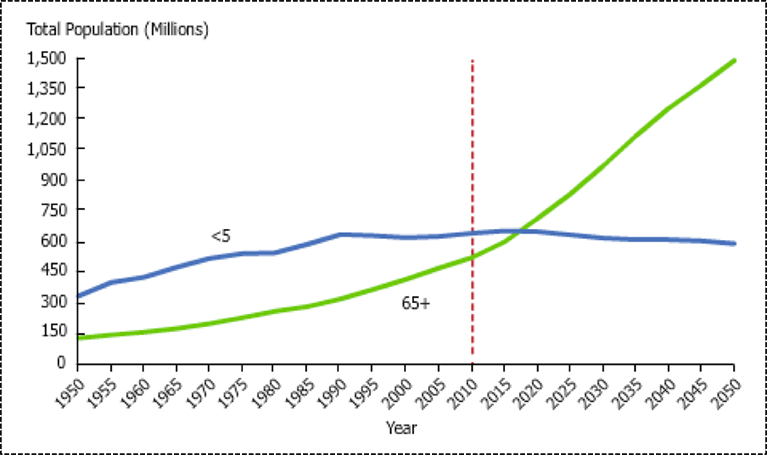

Calment was not the only person to live longer in recent decades. As the projections in Figure 1 show, the world population of those aged 65 and older will have increased by a factor of 10 between 1950 and 2050, and will have tripled between now and 2050. By 2050, it is projected that there will be about 2.5 times as many adults over age 65 as children under 5.

“Population Change Among Adults 65 and Older, Compared to Children Under 5”

In Figure 2, population pyramids of high-resource versus low-resource countries demonstrate that the proportion of people over 60 is projected to be higher in high-resource countries in 2050. However, as Figure 2 also shows, the older adult population is growing faster in low-resource parts of the world as well. By 2050, four of five older adults in the world are expected to live in low-resource countries. Globally, these changes are principally a consequence of falling birthrates and rising life expectancy.

“Population Pyramids of the Less and More Developed Regions: 1970, 2013 & 2050;” UN World Population Ageing Report 2013

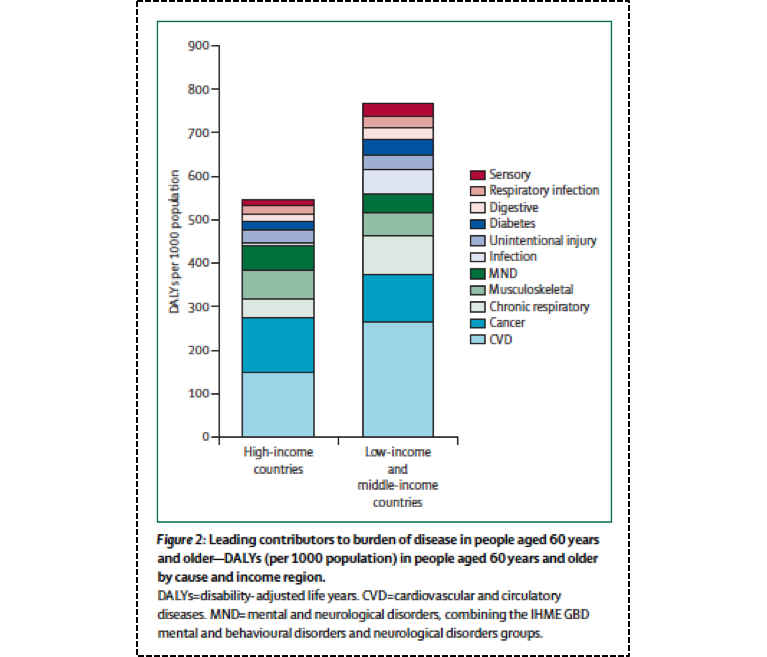

This demographic shift is, without a doubt, largely a positive development. Increased longevity is the happy result of improvements in the conditions that make populations healthy—triumphs of the efforts of public health. However, and importantly, as illustrated by the opening story, when people live longer, there are often costs involved—both expected and unexpected. How we handle these costs will affect the opportunities for healthier living that we create for ever larger numbers of people. Two key costs are disability and disease. Disability among older adults presently contributes to 23 percent of the global burden of disease; it contributes to half of the burden of disease in high resource countries and 20 percent of the burden in low resource countries. As Figure 3 shows, cardiovascular disease and cancer are the leading contributors to this burden. Estimates of changes in DALYs (Disability Adjusted Life Years) among older adults between 2004 and 2030 suggest that the DALYs for all causes will increase by 55.2 percent. DALYs attributable to communicable, maternal, perinatal, and nutritional conditions will fall by 18.7 percent, while those attributable to non-communicable diseases will rise by 61.3 percent and those attributable to injuries will rise by 78 percent. Specific diseases expected to rise most precipitously include diabetes (+95.7 percent), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (+88.7 percent), dementia (+82.6 percent), vision impairment (+86.3 percent), and hearing impairment (+70.6 percent). Cardiovascular disease and cancer are also projected to rise by 40.6 percent and 69.2 percent respectively. Countries that recently experienced an epidemiologic transition should expect sharper rises in the burden of disease due to these conditions. While the burden of chronic disease will increase most rapidly in low resource countries, high resource countries are more likely to see large increases in dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease. Whereas in 2006, the number of worldwide Alzheimer’s disease cases was 26.6 million, that figure is projected to quadruple by 2050, leaving one in 85 people in the world with this condition.

“Leading Contributors to Burden of Disease in People Aged 60 Years and Older in 2010;” from Prince, Martin J., Fan Wu, Yanfei Guo, Luis M. Gutierrez Robledo, Martin O’Donnell, Richard Sullivan, and Salim Yusuf.” The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice. The Lancet 385, no. 9967 (2015): 549-562

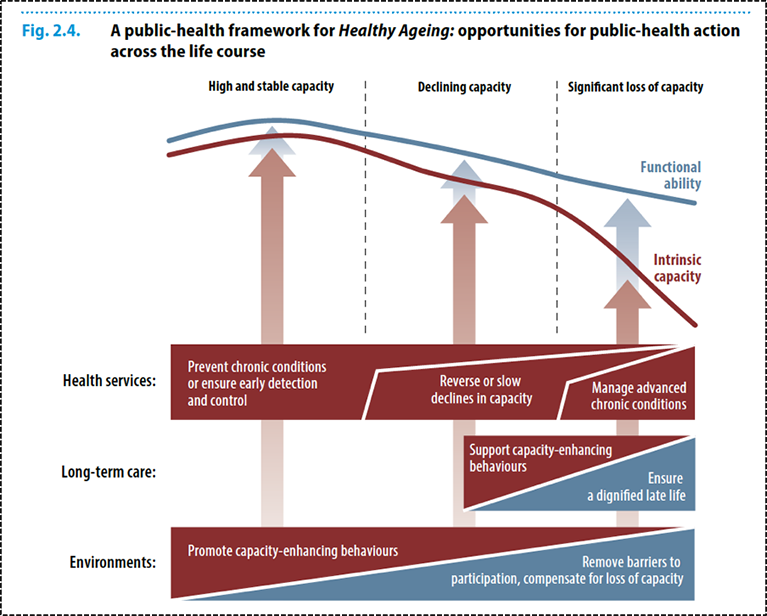

These challenges then represent a turning point for public health. How do we capitalize on the tremendous opportunities presented by this demographic shift, while also addressing the challenges that come with this change, so as to ensure healthier, productive populations going forward? The WHO public health approach to healthy aging, shown in Figure 4, represents a good place to start.

“A Public Health Framework for Healthy Ageing;” WHO World Report on Ageing and Health

This approach focuses on the promotion of functional ability—defined as “health related attributes that enable people to be and to do what they have reason to value,” and intrinsic capacity—defined as “the composite of all the physical and mental capacities of an individual.” Accordingly, the promotion of healthy aging aims to facilitate functional ability through “supporting the building and maintenance of intrinsic capacity,” and also by “enabling those with a decrement in their functional capacity to do the things that are important to them.”

The application of this approach, and the effectiveness with which it can be adopted globally, depends very much on geography and economic status. In many low-resource countries, for example, older adults have historically been cared for by families, a result of both necessity and social norms. As populations age, birthrates decline, and social norms change, however, this model becomes a less and less reliable means of providing stable, long-term care.

There is an opportunity, and a need, here for public systems to step into the role once played by families. Societies must become, on all levels, more welcoming of older adults and more keen to create structures that ensure the full participation of citizens of all ages. From advocating for more accessible built environments in our cities and towns to pushing for more volunteer opportunities for older adults to, at the political level, making sure that the needs of this population (particularly the homebound) are not forgotten, we have a chance to redefine what aging looks like in the decades to come.

Public health also strives to mitigate health gaps that exist among aging populations. In the US, race, for example, remains a persistent factor in determining health outcomes at all stages of life. The aging LGBTQ population also faces a distinct set of issues. Socioeconomic status remains central to the determination of health gaps for this population, as for all others. While increased total mortality among older adults can make the effects of income inequality harder to measure among older populations, economic resources remain a fundamental determinant of health in old age. Perhaps their most obvious effect is in determining the kinds of medication seniors can afford to take. As drug prices continue to rise, a public health strategy of prevention, implemented throughout the lifecourse, can ease the burden of the chronic and acute diseases that afflict older adults, and reduce the need for prohibitively expensive medication.

Broadening our scope beyond the prevention of disease, we find ever more areas where an engaged, creative public health approach can make a difference in the lives of seniors. From exercise programs to facilitate greater mobility, to home visits aimed at reducing isolation, to mentoring partnerships that give older adults a chance to pass on what they have learned to younger generations, there are an abundance of opportunities for structured intervention. Much work is already being done along these lines, not only to safeguard the health of older adults, but also to improve their quality of life. Here at SPH, the research of Lisa Fredman, Alan Jette, and Paola Sebastiani in particular, represent just the kind of nuanced work that a functional ability-based strategy calls for.

A change in perspective, then, from a focus on decreasing functional disability, to one of prevention and increasing functional ability, opens novel avenues towards promoting the health of older adults as we consider the coming large-scale population changes. Such an approach emphasizes prevention and maintenance of functionality. It militates for a shift away from considering our later years a period of decline to one where we see these years as a period of continual growth and improvement. This is a view that resonates well with public health, consistent with our effort to ensure we maximize opportunities for all people so they can live longer, better lives.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Gregory Cohen and Eric DelGizzo for their contributions to this Dean’s Note and to professor Lisa Fredman for critical editing and input. As always, any errors are mine alone.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/