A World without Public Health.

I hope everyone has had a terrific holiday break. I wanted to start the year by taking a look at the success of public health, to illuminate how much poorer the world we live in would be without public health.

I hope everyone has had a terrific holiday break. I wanted to start the year by taking a look at the success of public health, to illuminate how much poorer the world we live in would be without public health.

Improving the health of populations is the core ultimate goal of the academic health enterprise. Sometimes that goal seems pyrrhic, and I have in the past year commented a fair bit on the lives that could be saved by action on firearms, or perhaps less controversially, through better vaccination of populations.

However, over the past century, public health also has realized tremendous successes. We have much to learn, and perhaps celebrate, from the successes of the past. To that end, to start the year, we take a look at four of the triumphs of public health and their implications. We draw these four from the CDC’s Ten Great Public Health Achievements in the 20th Century and highlight advances related to tobacco, control of infectious disease, motor vehicle safety, and cardiovascular disease.

To articulate a frame, we ask the question: What would the world have looked like if we did not have success in each of these areas?

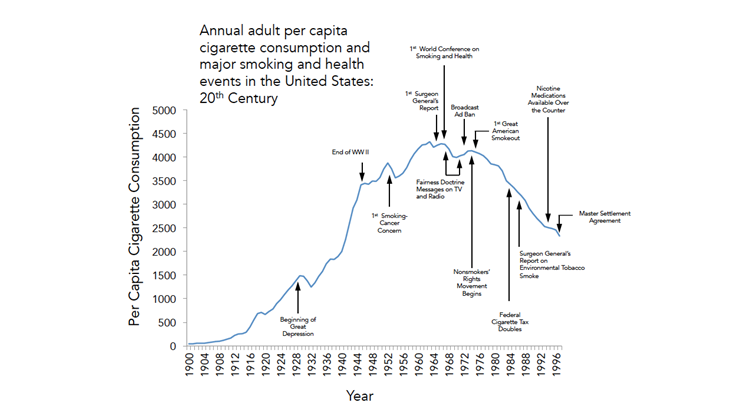

We start, perhaps inevitably, with the success of tobacco control in the United States in the 20th century. This success is attributable to many factors, including the enumeration of the health risks associated with smoking, the public health campaign to reduce consumption, and the changing of public norms towards smoking, and increased taxation. The rate of per capita cigarette consumption in the US in the 20th century is presented in Figure 1a, annotated with relevant events that contributed to this success.

Tobacco consumption in the 20th Century, adapted from figure 1 in : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1999). Tobacco use–United States, 1900-1999. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 48(43)

Figure 1a shows clearly that the doubling of the federal cigarette tax, the Fairness Doctrine, and the Master Settlement Agreement were all key inflection points in our progress towards improved tobacco control. These are textbook examples of macrosocial drivers that were instrumental in improving population health.

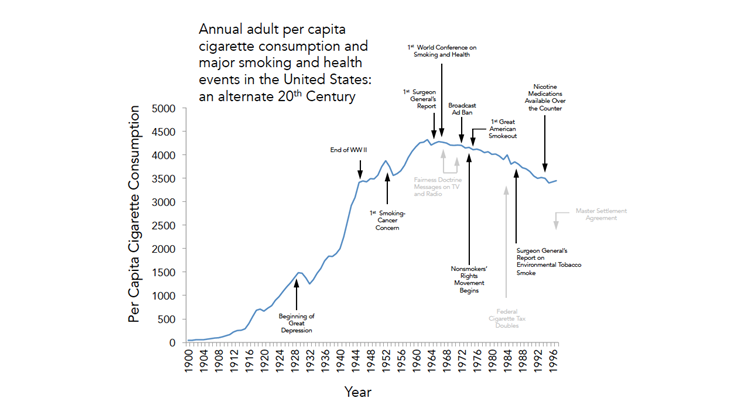

But what if these efforts had not been implemented? What if public health had not achieved this success? We could ask what would have happened if some of those tobacco control efforts had failed—for example, what if the federal cigarette tax had not doubled, and the Fairness Doctrine and the Master Settlement Agreement had not been passed? We represent one version of this alternate reality in Figure 1b.

Tobacco consumption in an alternate 20th Century, adapted from figure 1 in : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1999). Tobacco use–United States, 1900-1999. MMWR, 48(43)

Figure 1b assumes extends the pre-existing trajectory but removes some of the key public health efforts that inflected the shape of the tobacco consumption curve. What would have been the implications of this alternate reality? We would estimate that the difference between the original and revised curve represents 451 cigarettes per capita on average annually between 1968 and 1997. We know that at an ecologic level, consumption of 3 million cigarettes is associated with one lung cancer death, and that the time lag between consumption and death is 35 years on average. Performing an area under the curve calculation, this would then mean an excess of 1,005,778 deaths from lung cancer between 2003 and 2032.

Now we move on to the control of infectious disease, another major advance of the 20th century, attributable to a combination of sanitation and hygiene improvements, the advent of antibiotics, and universal vaccination programs. The crude annual death rate attributable to infectious disease deaths in the United States is presented in Figure 2a, annotated with key events of import.

Infectious Disease Control in the 20th Century, adapted from figure 1 in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1999). Achievements in public health, 1900-1999: control of infectious diseases. MMWR, 48(29)

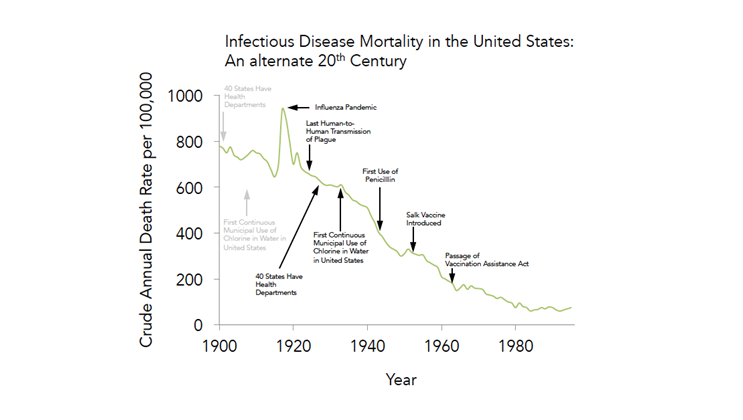

In this case we ask not what would have happened if key public health actions never happened, but rather if they were simply delayed. In Figure 2b, we present an alternate version, where the initiation of widespread state health departments and the continuous use of chlorine were delayed by 10 to 20 years.

What would this have meant? We estimate, based on the difference between the above two curves, that this would translate into an excess of 21,651,243 infectious disease deaths between 1900 and 1995.

Infectious Disease Control in an alternate 20th Century, adapted from figure 1 in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1999). Achievements in public health, 1900-1999: control of infectious diseases. MMWR, 48(29)

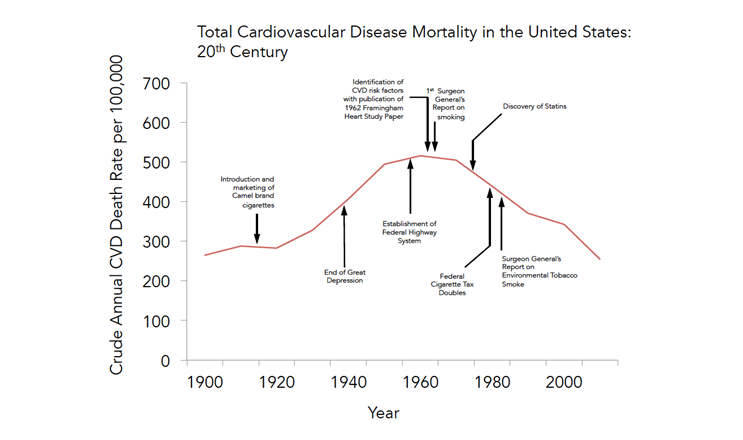

No we move on to the decline in cardiovascular disease (including stroke, coronary heart disease, and other diseases of the heart), one of the hallmark health improvements of the 20th century. This can readily be traced to many factors, including societal changes in diet and smoking habits and advances in medical care. In particular, these factors include the Surgeon General’s reports on smoking and environmental smoke, as well as the advent of statins.

In Figure 3a, we present the death rate due to total CVD from 1900 to 2010.

Cardiovascular disease in the 20th Century, adapted from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute statistics

Again, we could ask how this curve might have looked if those societal advances had not occurred, and we represent one such alternate reality in Figure 3b. Figure 3b supposes that the identification of CVD risk factors and the Surgeon Generals’ reports on smoking and secondhand smoke did not happen.

What would have been the consequences? According to our calculations, this would have resulted in 19,948,307 excess deaths between 1960 and 2010.

Cardiovascular disease in an alternate 20th Century; adapted from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute statistics

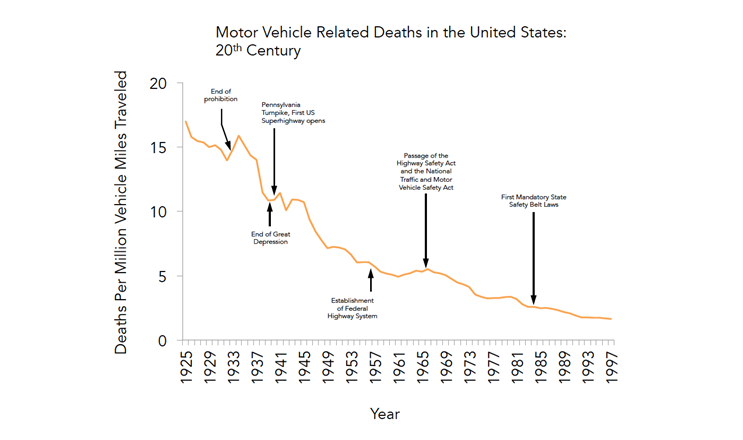

Motor vehicle safety is another of the great public health achievements of the last century and one of my favorite examples of structural change being associated with improved health. The core drivers of improved motor vehicle safety were federal regulatory efforts that improved the safety of vehicles and roads, changes in driving behavior and enforcement of driving laws, and public health communication efforts. Figure 4a shows the steep downward progression of the rate of death per million vehicle miles travelled over the 20th century.

Motor vehicle death rate in an alternate 20th Century; adapted from figure 1 in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1999). Achievements in public health, 1900-1999: Motor vehicle safety. MMWR, 48(18)

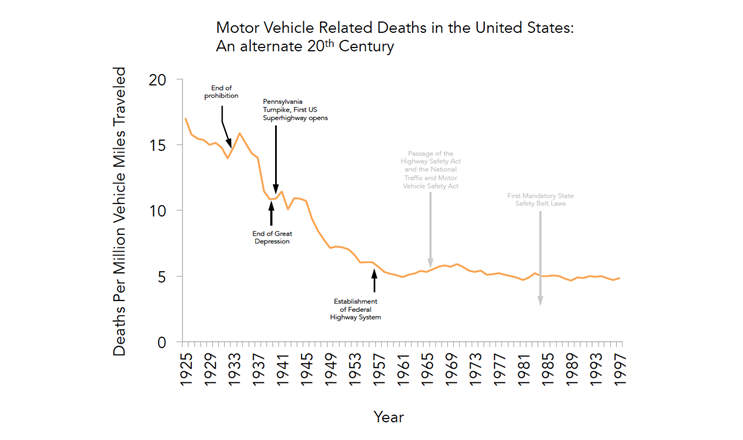

Figure 4b shows one alternate version of reality, providing one potential answer to the following question: What if regulation of motor vehicle safety and enforcement of motor vehicle laws was never instituted? Taking the difference between the two curves, we estimate that this would have meant an excess of 1,218,915 deaths in the United States between 1967 and 1999.

Motor vehicle death rate in an alternate 20th Century; adapted from figure 1 in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1999). Achievements in public health, 1900-1999: Motor vehicle safety. MMWR, 48(18)

Hence, we can well ask in dark moments, whither public health?

But a fresh look at the achievements of public health suggests that if key public health interventions did not happen or were delayed, we would see 48,834,243 excess deaths from four major causes of death, in the United States between 1901 and 2032.

Undoubtedly one could apply this exercise to many other triumphs of public health, including the extraordinary improvement in global health over the past 25 years. Here I simply wanted to highlight simply some key domestic examples to suggest quantitatively that a world without public health, even without public health action on only a few key efforts, would have been a world with far fewer people indeed.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Professor, Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

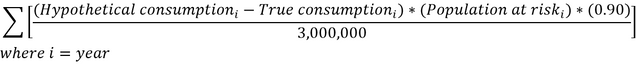

PS: For anyone who is interested in the math, to derive the above estimates we extended best-fit line beyond the date of the key public health action that we “deleted,” and then calculated the new area under the curve to obtain excess mortality:

The equation for motor vehicle related deaths is the same, with the exception that

![]() is substituted for

is substituted for ![]() .

.

In the case of cigarette smoking, assuming that consumption of 3 million cigarettes is associated with one lung cancer death and 90 percent of lung cancer in the United States is caused by tobacco, we obtained an estimate of excess tobacco-related lung cancer deaths associated with cigarettes consumed between 1968 and 1997 using the following formula:

Acknowledgement: I am most grateful for the contributions of Gregory Cohen, MSW, to this Dean’s Note.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.