Income and Health, Part 1.

I have long had an abiding concern with the macrosocial determinants of health—the cultural, political, and environmental forces that influence well-being at the level of populations—having written about them here many times. It occurred to me recently that I have never, however, written about what is perhaps the most foundational driver of all: income. My decision to do so now was prompted, in large part, by the recent election, and the prominent role that economic inequality played in fueling voter anger and the rise of Donald Trump. The release of the US Census report on household income and poverty was another acute reminder about the centrality of income and poverty to all our social structures. That report—worth a read—showed that incomes were rising for many Americans in the middle of the income distribution, and that the income gaps between the richest and the poorest quintiles have continued to widen.

I have long had an abiding concern with the macrosocial determinants of health—the cultural, political, and environmental forces that influence well-being at the level of populations—having written about them here many times. It occurred to me recently that I have never, however, written about what is perhaps the most foundational driver of all: income. My decision to do so now was prompted, in large part, by the recent election, and the prominent role that economic inequality played in fueling voter anger and the rise of Donald Trump. The release of the US Census report on household income and poverty was another acute reminder about the centrality of income and poverty to all our social structures. That report—worth a read—showed that incomes were rising for many Americans in the middle of the income distribution, and that the income gaps between the richest and the poorest quintiles have continued to widen.

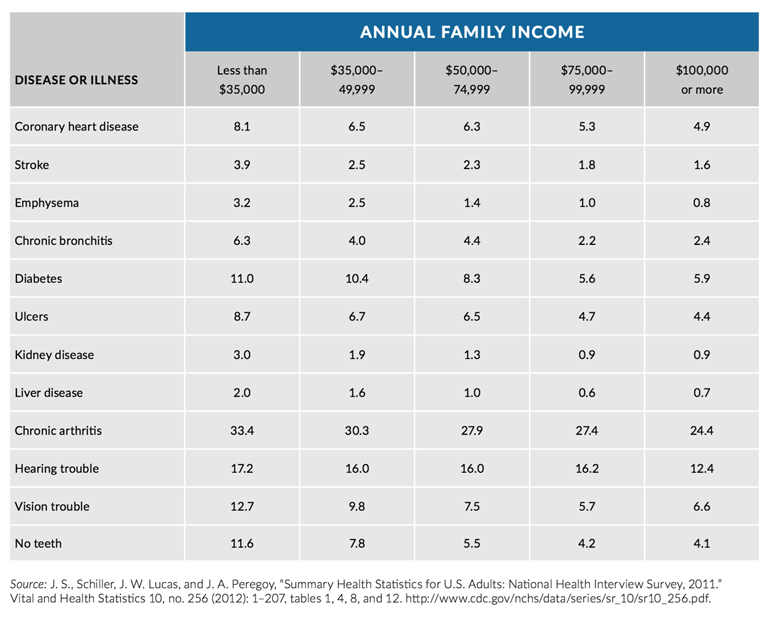

Fundamentally, income is directly related to health on all axes, and has been since time immemorial. For example, William Farr, in his 1841 study of mortality in English asylums, found that death rates were higher among poor patients. Jumping to the present, a 2016 UNICEF report found that, globally, children born into the poorest 20 percent of households are nearly twice as likely to die before reaching the age of 5 than those born into the wealthiest 20 percent. Income is also associated with any number of chronic diseases. Figure 1 below illustrates the 2011 prevalence of disease among adults by income, showing less-advantaged adults to be at higher risk for any number of conditions, including heart disease, stroke, and diabetes.

Woolf SH, Aron L, Dubay L, Simon S, Zimmerman E, Luk K. How Are Income And Wealth Related To Health And Longevity? http://www.urban.org/research/publication/how-are-income-and-wealth-linked-health-and-longevity Published April 2015. Accessed November 28, 2016.

A Note, then, on the influence of income on health, and the mechanisms through which income shapes the health of populations. I will confine my comments today to the domestic context, respecting the complexity of income’s link to health, and how this relationship can vary in different parts of the world.

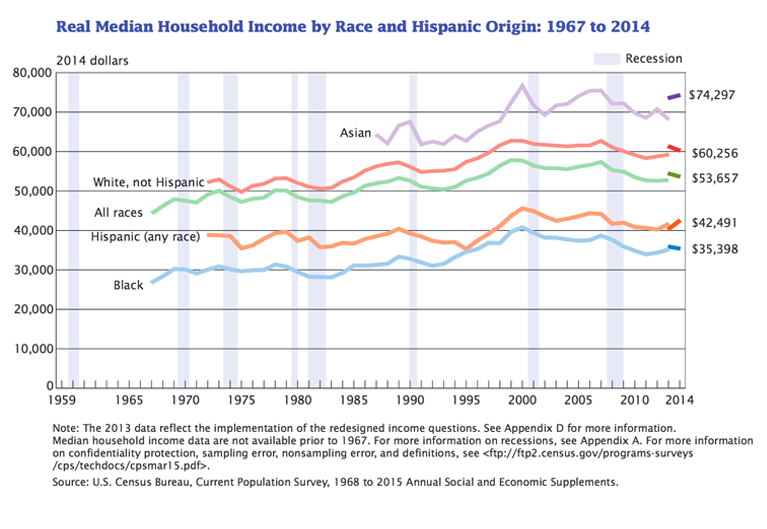

The foundational drivers of health, particularly forces like income that shape social divides, are inextricably linked to our understanding of health divides. The relation between income and health underlies many of the health gaps that we see in the United States between groups. In 2014, the US Census Bureau reported the median household income as $53,657. However, that median was not the same for all populations. For Asians, the median household income was $74,297; for white non-Hispanics it was $60,256; for Hispanics $42,491; for blacks $35,398 (Figure 2). The magnitude of these differences has proven to be persistent. With the exception of non-Hispanic white households, whose median income declined by 1.7 percent between 2013 and 2014, changes in income among racial groups during this same period were not statistically significant.

DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2014, Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2015.

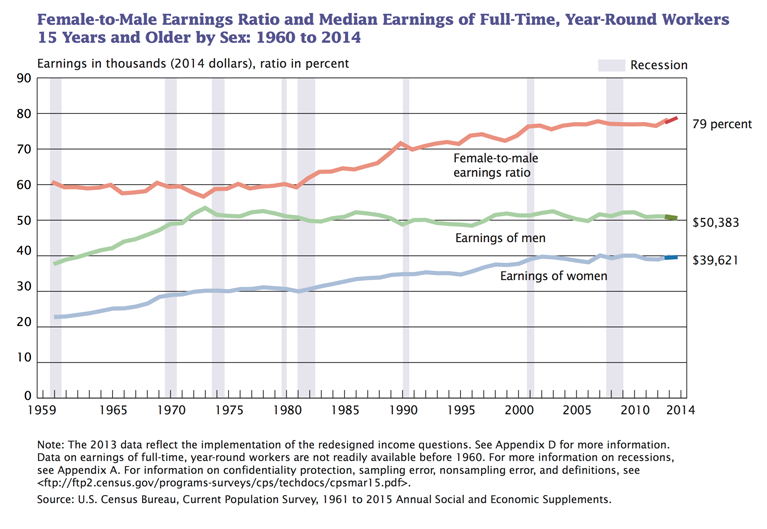

The Census Bureau also reported a gap between median yearly income for women and men, with women earning $39,621 in 2014 and men earning $50,383. The female-to-male earnings ratio for that year was 0.79 (Figure 3). This gender wage gap has its own unique health implications, and ties in with the larger picture of gender inequity, itself an enormously consequential determinant of well-being.

DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2014, Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2015.

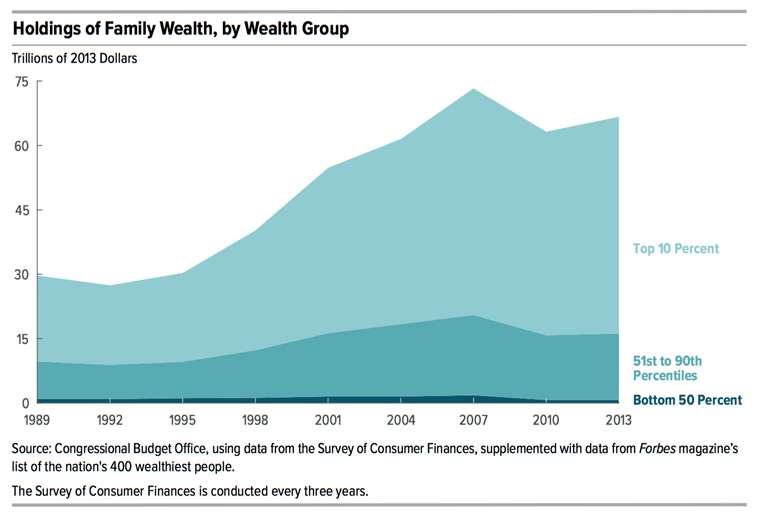

When we discuss income, it is difficult to avoid also discussing wealth. Wealth, in many ways, compounds the effects of income. Definitionally, income is simply a flow of money that is received by groups or individuals. Wealth is a stock that people may draw on to support their livelihoods or—in the case of debt, i.e. negative wealth—an expense that must be paid down, reducing the proportion of income that can be used for goods and services. While income delineates haves and have nots in the US, this difference is deepened when one considers wealth and wealth gaps. In Trends in Family Wealth, 1989 to 2013, the US Congressional Budget Office found the aggregate family wealth in this country to be $67 trillion in 2013, more than double the amount of family wealth in 1989. However, this increase has not been shared equally. In 2013, 76 percent of all family wealth was held by families in the top 10 percent of the wealth distribution (Figure 4). Further, intergenerational transmission of wealth leads to large, and persistent disparities between groups, and is one way that the history of this country (of slavery, of union-busting etc.) is marked on.

Congress of the United States Congressional Budget Office. Trends in Family Wealth, 1989 to 2013. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/51846 Accessed November 28, 2016.

This problem of income inequality has received much attention in recent years. Its relation to health is complex, affecting those at the top and the bottom of the economic ladder in very different ways. Although the literature on this is sparse, there are some studies that have shown the direct relationship between wealth and health. I will comment more on health and income inequality in next week’s Dean’s Note.

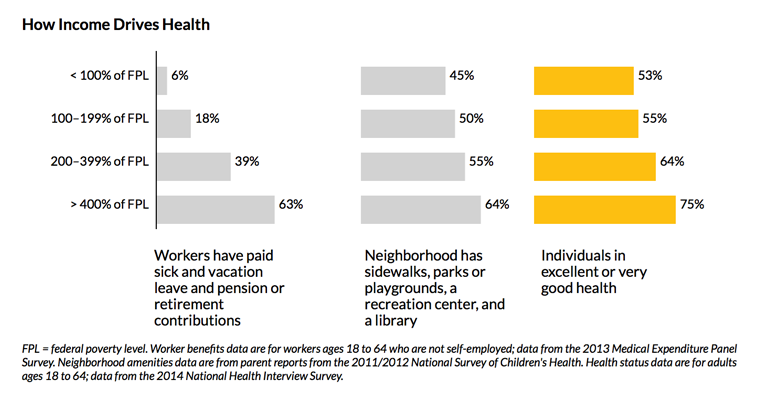

It is clear that income is inextricably linked to health; and income, or at least the factors that lead to divergence in income, are very likely fundamental determinants of health. How, then, does income influence health? Our income shapes our circumstances, from the neighborhood we can afford to live in, to the food we can afford to eat, to our opportunities for social and educational advancement. It also determines the quality of health care we can afford, and the treatment possibilities available to us in the event of illness. These factors all contribute to overall well-being. Low-resource neighborhoods, for example, can be more polluted, more dangerous, and less food-secure than more affluent communities. These disadvantages can carry over into the classroom. High-income parents are better able to invest in the academic development of their children, giving their kids scholastic opportunities that less advantaged children too often lack. Education, as I have commented previously, is closely linked to health and can lead to higher-paying jobs that provide greater stability and fewer health risks. And while our environment, education, and employment are all important by themselves, taken together they represent a broader web of circumstance, one that can either reinforce or undermine health. With good jobs comes the money to live in good neighborhoods and access good schools, driving a “cycle of health,” well reflected in Figure 5.

The Picture of Health: At Home, at Work, at Every Age, in Every Community. Urban Institute Web site. http://apps.urban.org/features/picture-of-health/index.html Accessed November 28, 2016.

It is perhaps unsurprising that, on the other end of the economic spectrum, being poor has been linked to chronic stress, undermining the emotional and physical health of low-resource populations.

Like the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the political system under which we live, the very ubiquity of income’s influence can make it easy to take for granted, or even ignore. However, it is this very ubiquity that agitates for maintaining, at the heart of population health science and practice, a concern for the link between income and health. This suggests, for example, a focus on scholarship that aims to understand the role of income, and how best to mitigate the consequences of low income, and to redistribute income if such redistribution can be shown to improve population health. How will minimum wage regulations influence population health? Transfers such as EITC, food stamps, and WIC? What are educational interventions that can break the cycle of poverty? How can affordable housing be best made available to create income-heterogenous urban neighborhoods? Similarly, we have a role in advocacy around these issues, working to keep health at the center of the continuing conversation about income inequality. This means, centrally, shifting the focus of the debate from the concentration of wealth at the top of the economic ladder to the conditions of poverty at the bottom. Increasingly, I am coming to feel that this is one of the hidden/unspoken challenges to our society, and one that is key to public health—the circumstances of the bottom 50 percent, who have no passports, have abysmal incomes, and abysmal health indicators. In next week’s Dean’s Note, I will take a closer look at these circumstances, the problem of poverty, and the role of public health in mitigating these problems.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Eric DelGizzo and Professor Jacob Bor for their contributions to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.