Suki and colleague Bates publish first book to guide pulmonary researchers in methods of modeling

By Patrick L. Kennedy

Modeling the lung? Professor Béla Suki (BME, MSE) wrote the book on it. Or to be precise, he co-authored it. Suki and longtime collaborator Jason Bates have crafted an advanced textbook that should long serve as a bible for researchers using models to elucidate the complex network of fibers that make up the human lung. Mathematical Modeling of the Healthy and Diseased Lung (Springer, 2025) is the first book of its kind in the pulmonary field.

“There are no equivalent books on the market,” wrote one pre-publication reviewer. “While the [intended audience] is currently small, the potential for impact is quite large.”

A vital organ hard to predict

From asthma to emphysema, respiratory diseases afflict millions, killing many. Lung cancer, for example, is the deadliest form of cancer, and 1.2 million people died of COVID-19 in the U.S. alone. But compared to the heart, the equally vital lung—actually a pair of organs, each a moving maze of airways and ducts—has proven difficult to model, even since the advent of computational methods. And so, relatively few pulmonology researchers have been able to produce the robust visualizations and predictions that would enhance our understanding of the causes of, and potential treatments for, lung diseases.

Now, however, the discipline is poised to grow, thanks in no small part to the efforts of Suki and Bates—both as the co-authors of what promises to be a foundational text for the field, and as pioneers in the practice of creating virtual laboratories to study pulmonary phenomena.

Bridging fields

In 2015, the National Institutes of Health granted a major award to Suki, with his team at Boston University, and Bates, who runs a lab at the University of Vermont, to study the extracellular matrix of the lung, using computational models. Former physicists both, the duo have since built up a wealth of knowledge on the impacts of physical forces on cell function, with a particular focus on the lung. For example, they developed an important computational model of the progression of pulmonary fibrosis.

The new book draws upon that pool of experience and expertise—encompassing physiology, physics, estimation theory, modeling, complexity and nonlinear systems—as well as relevant literature across those fields. Synthesizing all this, the authors offer a coherent guide that will likely benefit readers ranging from PhD students and postdoctoral researchers to pros well into their careers. “Because computational biomedical engineers might not have much background in pulmonary physiology, and vice versa,” Suki points out.

“We try to cover the tools and ideas you might need to understand the phenomenon behind a lung disease,” Suki says. “Pick any disease. The lung’s cells are producing and receiving signals, and then in response, behaving in certain ways. And there are about 50 cell types in the lung, and maybe 100 different signaling molecules that they can exchange. How can you model this? One tool to use could be partial differential equations that describe the spatial and time variations of certain chemicals that are released.”

Do the math

Advanced equations are what underlie effective models, Suki says, but modeling—devising a simplified version of reality—has been a tool of science at least since the Ancient Greeks’ time. In fact, modeling comes naturally to us humans, whether we realize we’re doing it or not. “If somebody throws you a ball, your brain somehow computes the trajectory, and you’re able to catch the ball,” Suki says.

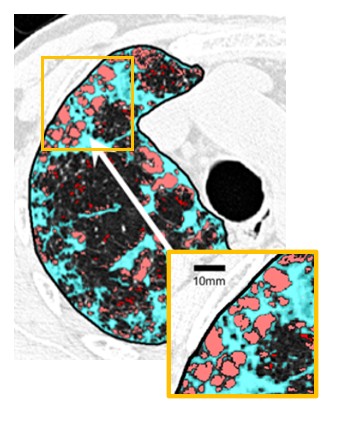

Some key tools the book explores include network modeling and agent-based modeling. For example, in pulmonary fibrosis, the disease “percolates,” says Suki. “People usually don’t have symptoms for a while, then suddenly they have chest pains.” By the time a patient seeks help, it might be too late. An agent-based model—in which certain properties and behaviors are assigned to “agents,” in this case representing cells—can describe this process from the beginning, showing how first one region of the lung stiffens, then another.

Taking it further

Agent and network modeling can even be combined for a richer analysis, as Suki has lately been doing to explore the effects of aging on the lung. Aging is a surprisingly under-studied topic that Suki hopes other pulmonary researchers will focus on.

“Somebody could take the ideas in this book and advance them further,” Suki says, “to create even better and more realistic computational models.”

Indeed, while Mathematical Modeling might be a watershed publication in a young field, Suki doesn’t want it to be the last word. He likes to quote statistician George Box: “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” Then, fittingly, Suki expands upon that quote with his own twist: “The ultimate usefulness of a model manifests when it is replaced by an even more useful model.”