Greater Than the Sum of Their Parts

Undergraduate Researchers and Mentors Move ENG Forward

By Sara Cody

Ribbons of neon light undulate in the northern night sky, a technicolor display of pinks, greens, yellows, blues and reds against a backdrop of stars. They have captured the human imagination for millennia: the ancient Greeks thought they marked the gates of the home world of their sun god Apollo; the Celts thought them angels at war in the sky; the Norse believed they led fallen soldiers to Valhalla. Only in the last century did we learn that the auroras around the poles are caused by disruptions to charged particles in the atmosphere, causing them to crash into each other and emit the otherworldly light.

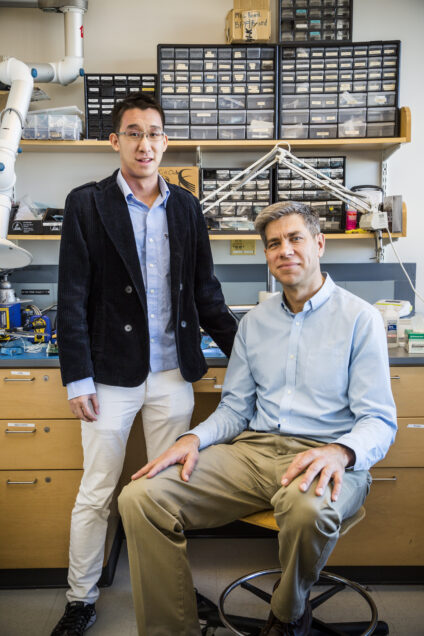

We are still learning about the way the Earth’s atmosphere interacts with our near-space environment and Phillip Teng (BME ’19) is playing a major role in a NASA-funded satellite research mission to study the phenomenon. He is one of about 150 College of Engineering undergraduates working with faculty mentors on their research each year. It’s a chance for students to hone their problem-solving skills on projects that have real-world impact – and to get a leg up on getting into graduate school or their first career job.

Teng’s mentor, Professor Joshua Semeter (ECE), says that while the students are learning about engineering, engineers are learning from their research. “When you think about it, we’re creatures walking around on a planet that is continuously buffeted by a solar wind full of harmful ionizing particles that are deflected by our magnetic field. Humans evolved within this protective magnetic bubble, and my research is focused on figuring out how that works while exploring the roles it played in our origin and will play in our future.”

Teng is working on Semeter’s project ANDESITE, an interdisciplinary project funded by NASA and run by students to study changes in Earth’s magnetic field caused by interactions with space, such as the aurora. When it comes to satellite research, the approach is usually to send a single, costly satellite that can only collect data in its immediate area at any given time. ANDESITE aims to send eight picosatellites, DVD-sized mini-satellites outfitted with electronics boards, along on a NASA spacecraft that will spit them out roughly 280 miles above the Earth. Each sensor will complete an orbit of the Earth in about 90 minutes. The sensors will measure variations in electrical currents flowing in and out of the upper atmosphere along Earth’s magnetic field. Teng’s primary role is constructing the magnetic sensor that will collect the data after the satellite launches.

“The idea is to collect data across space from multiple points across the aurora and use that information to analyze the magnetic fields,” says Teng. “There are certain assumptions you have to make when you only have one point of data to work with, but now that we have this volume of space with data you have more to work with. You get a better, more accurate idea of the spectrum of data instead of just being confined to one point.”

Regardless of whether undergraduates wish to pursue research as a career path, having research experience is invaluable. Not only is it a way for them to apply the theoretical concepts they learn in class to solve real-world problems, but it also allows them to develop critical thinking and soft skills—networking, communication, presentation — that are necessary to thrive in a professional work environment. And they are not just washing beakers and covering basic laboratory preparation—they are working in tandem with accomplished faculty, conducting real research that will advance their field. In many cases, they even have the opportunity to publish their findings in an academic journal. For many students, it helps solidify their own career pathway to academia, but even if they ultimately do not pursue a career in research, it is a great resume booster.

“For students, getting this research experience opens up all kinds of doors for them,” says Semeter. “Not only do the students usually get a great recommendation letter out of it, it can be a defining experience to talk about during a job interview, because they have very specific roles that they are able to talk about in depth. It really helps them stand out to future schools and employers.”

According to Semeter, while prior knowledge on a research topic or a perfect academic record can be helpful, qualities like initiative, commitment, and a willingness to learn are far better indicators of how students will perform in their first research experience. And he is not alone. Both the College and BU as a whole offer a variety of ways to connect researchers to eager undergraduate students. And it isn’t just an experience that benefits the undergraduate students; they are a vital component of a laboratory ecosystem.

“I have found that if you put a challenging objective in front of a student, they rise up and solve the problem that’s needed. I’ve seen it over and over again. It’s unbelievable what our undergraduates can accomplish,” says Semeter. “But it does take mentoring and advising to keep them on track because they are still learning. As long as you have someone guiding them in the right direction they will succeed.”

WORKING SHOULDER-TO-SHOULDER

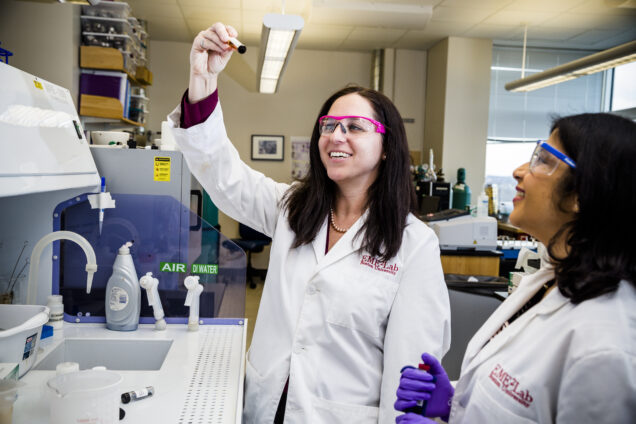

It can be difficult to see trash as anything but one of the most prolific causes of global environmental woes. But Chitanya Gopu (ME’17) and her mentor Research Assistant Professor Jillian Goldfarb (ME, MSE) saw potential to turn trash into sustainable energy and materials that can help the environment in a big way.

“My summer research project focused on converting municipal solid waste and into energy and activated carbons, which could be used to treat the leachate, or runoff, from landfills,” says Gopu. “The idea was to create an integrated system where even the byproducts benefitted the environment in some way.”

When Gopu took an environmental engineering course taught by Goldfarb, Gopu immediately felt a connection with her, especially after learning how her research was closely connected with Gopu’s own career goals to benefit the environment. She reached out to Goldfarb to see if there were any research positions open. Goldfarb worked with her to craft a summer research project, which Gopu was able to complete thanks to the Summer Term Alumni Research Scholars (STARS) program, an alumni-funded College initiative that provides a living stipend to undergraduate students who wish to pursue a full-time research project with a faculty member over the summer. Gopu is in the process of wrapping it up by writing her second academic journal article, for which she will serve as first author. Goldfarb’s philosophy is to work with the students to come up with a project aligned with their studies and goals, and ultimately give them ownership over it.

“My students have their own project that they manage, so they’re accountable for it, and if it doesn’t happen, then they don’t have a project. My theory is if you do the heavy lifting, you get the credit,” says Goldfarb. “And in my lab, everyone washes their own beakers, even me.”

For Gopu, one of the most eye-opening experiences of conducting research is just how integral failure is to the research process. Organic learning through discovery differs greatly from classroom laboratories, where the steps are predetermined and students have an idea of how to get from A to B.

“Everything I need to know I have to figure out myself, and while Professor Goldfarb is a great resource for advice, since these are new questions we are exploring, there isn’t necessarily anyone who has all the answers yet,” says Gopu. “In a real laboratory setting, things never work the way you expect them to the first time, and you gain a lot of experience by learning to work through things.”

As Gopu wraps up her summer research and moves on to her newest project — working with ultrapure chemicals to fabricate and test a nanotechnology-based material to treat water samples — Goldfarb has noticed a significant transformation in Gopu’s ability to draw her own conclusions from her data.

“Since living through the process of ‘try, fail, try again’ in her first project, Chitanya is working through problems confidently and much quicker this time around, and that lowering of the activation energy barrier made me realize how much she has grown,” says Goldfarb. “Learning from prior failures and turning them into successes has allowed her to grow much faster in her current project.”

For Gopu, the laboratory has been a positive experience and has solidified her own desire to continue her career path in research. She is currently working on applications to graduate school, with help from Goldfarb.

“When creating my material for my first project, I knew the experiment worked properly when I saw it change from solid trash to liquid fuel, and when it did, it was honestly the greatest feeling,” says Gopu. “No matter what you do after college, the things you learn in the classroom won’t always appear exactly as you learn them, but it is so great to piece together knowledge from different areas, and it is so gratifying when your ideas materialize right in front of you.”

In addition to gaining valuable real-world experience, another benefit for students working in a lab is getting to see a different side of the professors. Instead of disseminating knowledge from the front of a classroom, students and professors work in tandem, learning together the entire way.

“I certainly hope that what my students get out of it is a different perspective on engineering and the things they can accomplish with their degree,” says Goldfarb. “It’s amazing when students get their hands dirty and they figure out they have these skills they never knew they had. It can transform the way they think of themselves in terms of being an engineer.”

A FRESH PERSPECTIVE

Varnica Bajaj (BME’19) arrived on campus her freshman year on a mission to find hands-on laboratory experience. In high school, she worked on a nanotechnology project exploring drug delivery for curing cancer. The research was primarily theoretical, but she gained a wealth of experience in academic writing. Exploring cures for cancer led to her decision to pursue a pre-medical track at BU with the goal of becoming a surgeon and she realized that biomedical engineering was the right path for her.

“My sense is the future of medicine won’t just be about medicine, it will entail this revolution towards technology,” says Bajaj. “I decided to study biomedical engineering to better prepare myself for the future, because I thought I could apply an engineering mindset to the medical field.”

Using the BU Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP) website as a resource, she identified professors conducting research that interested her and sent out a flurry of emails introducing herself. She heard back from Professor Christopher Chen (BME, MSE), who connected her with her now-mentor, postdoctoral researcher Styliani Alimperti, who set her up to assist with a project focused on angiogenesis, or growing blood vessels, in a dish. Postdoctoral researchers professionally conduct research in a laboratory after they complete their doctorate degree with the goal of furthering their research and teaching experience to prepare for a career in academia.

“Initially, I was unaware that angiogenesis plays such an important role in health and disease, but when you think about it, there is an opportunity to make a tool that has real impact,” says Bajaj. “I would love to combine materials sciences with directed drug delivery and angiogenesis to find treatments for cancer and other autoimmune disorders.”

In Chen’s lab, Bajaj’s project focuses on building an in-vitro, cell-culture-based device that can mimic the complex behaviors of kidney filtration function, a model that she worked on during her summer research project. This technology would allow researchers to study a variety of diseases in a more controlled, cost-effective environment without having to use live animals for testing.

After using a polymer mixture that includes collagen – a naturally-occurring protein found in connective tissue – to form a scaffold, the cells that form the blood vessel are adhered to the structure. Bajaj injects two main types of cells that make up blood vessels: endothelial cells, which line the inside of blood vessels; and pericytes, which wrap around endothelial cells to keep them healthy. Historically, researchers have examined the effects of endothelial cells on angiogenesis, but this work looks at how both types of cells work together in this context. By inducing angiogenesis, Bajaj can examine the migration of cells around the body, as well as how new vessels are formed.

“It’s a project that involves trial-and-error, where many different experiments have to be tried before a solution is found. That’s why it is really important to find students who are committed and are able to make time between their classes and activities to get to the lab,” says Chen. “Varnica puts a lot of time into the work and it’s a project that we are very excited about.”

Since Chen holds a dual appointment at Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, Bajaj also has access to equipment and resources there, allowing more exposure to how research is conducted at another institution. While the work and its potential impact is a motivating factor, Bajaj counts her close working relationship with her mentor Alimperti, as particularly inspiring. Bajaj immediately felt a bond based on their shared experience as international students experiencing a new culture—Alimperti is from Greece, while Bajaj hails from Abu Dhabi.

“Research is interesting because you have your end goal, but you have no idea how you will get there. The uncertainty of the journey is constantly interesting and the faith in the final goal is what keeps me going,” says Bajaj. “But I love working with the people in my lab the most. It’s hard to not be inspired by these people who are doing fascinating work that can have such a widespread impact, especially my mentor. She provides guidance not only for the project and my academics but my future plans, too.”

According to Chen, the undergraduate students are not the only people in the laboratory environment who benefit from these experiences. The goals of academic research laboratories are two-fold: to advance our knowledge; and to train the next generation of researchers, which includes preparing graduate students and postdocs who wish to continue in academia with mentoring experience. Additionally, new students’ unfamiliarity with the world of research can sometimes be a virtue, because oftentimes they provide a fresh perspective that can revitalize the work at hand.

“Oftentimes, you have these highly specialized senior researchers who have been staring at the same problem for years,” says Chen. “Engaging with undergraduates provides an opportunity to reexamine the work from its basic principles, which can renew your own understanding of what is going on. That process of diving into the minutiae and pulling back out to a wider audience is a very important part of what we do as scientists, and undergraduates play a key role in that.”

ENJOYING THE JOURNEY

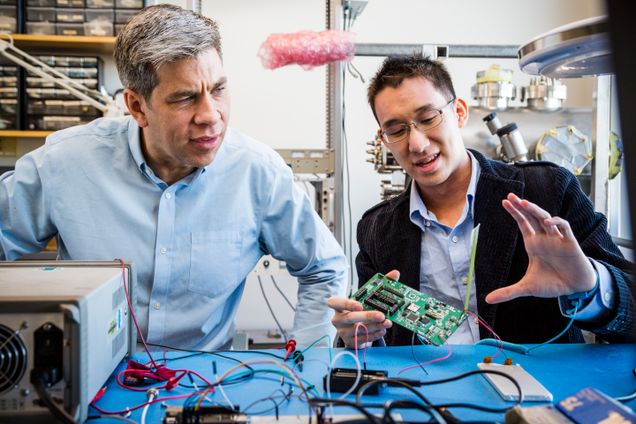

For Teng, while sending something he worked on with his own hands on a NASA space mission is great motivation, the process is even more enjoyable than reaching the goal itself. An avid swimmer, he equates his thinking to how he feels about swimming.

“I don’t swim because I want to get into the Olympics. I swim because I enjoy the act of swimming itself,” says Teng. “For me, working in the lab is a similar experience. While it will be cool to say that I contributed to this project, the physical aspect of working with circuits, soldering stuff together, writing the code that goes into it, thinking about how these different subsystems work and the logistics behind it is what I really enjoy.”

Teng first connected with Semeter after taking a required undergraduate course on circuits during his freshman year. Though he is a BME major, Teng had worked with circuits extensively in high school. After a few conversations with him in class, Semeter knew Teng was exactly the type of student he wanted in his laboratory.

“In my experience, I have found that students who take initiative to seek out the position themselves also proved to be successful in the lab, regardless of major or in some cases, even grades,” says Semeter. “Sometimes, you may have a student where the grades aren’t necessarily stellar or they may have a different motivation than just cracking a book, but they may excel working with their hands in a laboratory setting. It’s an opportunity to educate a different style of learner and give them a platform to excel.”

Balancing laboratory work with classes, homework, extracurricular activities and a social life can make for a busy schedule, but learning time management skills early on is a precious skill that can reap great rewards in the long run. Balancing his schedule with working on the project has even led Teng to consider incorporating computer engineering as a double major with biomedical engineering, a result of the multidisciplinary nature of the work between systems, computer and mechanical engineering, as well as other areas of science such as physics and astronomy.

“It’s tackling each individual problem one by one and those problems require so much depth and research. Between the scope of the project, and its complexity, it’s definitely the most difficult thing I’ve ever done,” says Teng. “But I know at the end of it all it will be my greatest accomplishment so far. Having Professor Semeter and the rest of the team as a resource for both my project and for career and life advice in general has been amazing. Their passion is contagious.”