College Campus Alcohol Policies Show Room for Improvement.

About 35 percent of US college students reported binge drinking—consuming five or more drinks on a single occasion—last year, and alcohol contributes to thousands of college student injuries, instances of sexual violence, and death. Substantial research has examined and informed effective policies for preventing alcohol-related problems in the communities surrounding campuses, but on-campus alcohol policies have received little attention.

About 35 percent of US college students reported binge drinking—consuming five or more drinks on a single occasion—last year, and alcohol contributes to thousands of college student injuries, instances of sexual violence, and death. Substantial research has examined and informed effective policies for preventing alcohol-related problems in the communities surrounding campuses, but on-campus alcohol policies have received little attention.

Now, a new study led by a School of Public Health researcher finds that college campus alcohol policies show room for improvement.

The study, published in the journal Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, demonstrates a new, evidence‐ and expert‐informed assessment approach for campus alcohol policies, and finds that most schools may not be implementing all of the most effective policies.

“Every school has alcohol policies, but they often do not reflect the public health evidence,” says study lead author David Jernigan, professor of health law, policy & management. “Our assessments can help guide campus leaders toward measures more likely to succeed in ensuring student health and safety.”

Previous systems that researchers have put forward for evaluating campus alcohol policies are fairly subjective, Jernigan and his colleagues wrote. Building from that earlier work, the authors of this new study designed a more objective and replicable assessment system, which they applied to information from the websites of the 15 member schools of the Maryland Collaborative to Reduce College Drinking and Related Problems, a voluntary statewide collaborative.

First, the researchers evaluated the accessibility of the policies on the colleges’ websites, including how many in a series of specifically worded Google searches it took to find a college’s policies, how many different pages the policies were spread across, and the Microsoft Word readability score of the policy language. Using this system, the researchers found that the campus alcohol policies were generally spread across multiple locations but took less than 30 seconds to find. None of the colleges had policies that scored well for readability: even the best-scoring school’s policies were written at a level best understood by a college graduate, rather than a high-school graduate (or incoming college freshman).

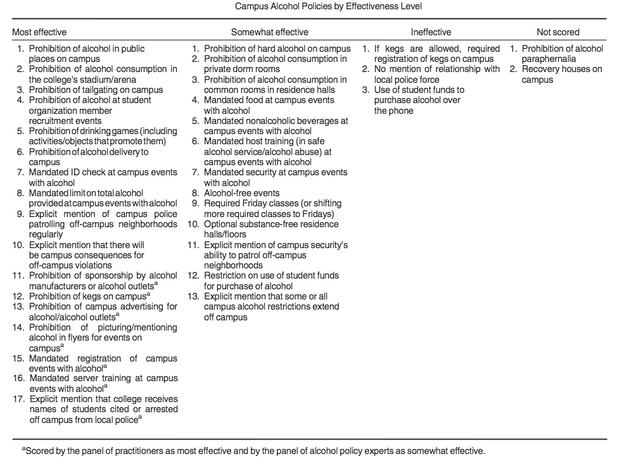

Next, the researchers compiled a list of the 35 alcohol policy elements found on the colleges’ websites. These policy elements were evaluated for effectiveness by a panel of five alcohol policy experts, and by another panel of seven practitioners—members of the Maryland Collaborative’s Advisory Board. The two panels came to similar conclusions in their effectiveness ratings.

The most effective policy elements were the ones that were likely to comprehensively affect the physical and/or normative drinking environment on campus. The panelists rated policy elements with limited or mixed-result research as somewhat effective, and they rated policies as ineffective if research/experience showed them to be such. The panelists also designated some policy elements as “not scored” when they were symbolically important but not practically important, or when they benefited a subset of students but would not have an effect on the larger student body.

The researchers found that the majority of the schools had less than half of the most effective or somewhat effective policies in place, and ineffective policies were not uncommon—showing room for improvement.

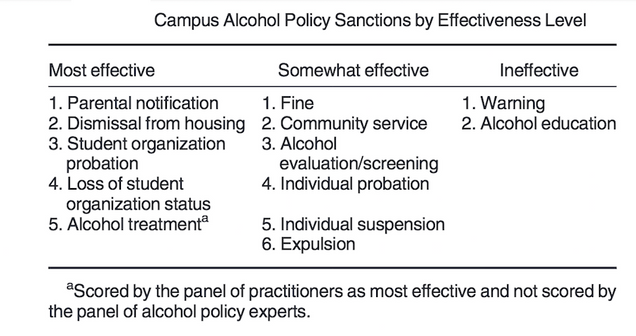

The panels also ranked 13 sanctions—the consequences that students would face if they violated their schools’ respective alcohol policies. They found that most of the schools had the most effective sanctions in place, although somewhat effective and ineffective sanctions were not uncommon.

The study was co-authored by Kelsey Shields of the University of Chicago, Molly Mitchell of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and Amelia Arria of the University of Maryland School of Public Health.