Revisiting the US Opioid Epidemic.

This month, our school will host two events addressing the US opioid epidemic. First, on January 25, we will host VADM Jerome M. Adams, the current Surgeon General, for a Dean’s Seminar about the epidemic. Dr. Adams will be joined for this discussion by Dr. Monica Bharel, the Massachusetts Commissioner of Health, and by Dr. Jonathan Woodson, the Former Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs. Then, on January 31, we will host Dr. Sally Satel, Resident Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, and Consulting Psychiatrist at Partners in Drug Abuse Rehabilitation and Counseling Clinic. Dr. Satel will discuss the implications of the opioid crisis within the context of the social and cultural drivers of addiction. These events follow our opioid-related programming from late last year, when we hosted the inaugural summit of the Police Assisted Addiction and Recovery Initiative (PAARI).

This month, our school will host two events addressing the US opioid epidemic. First, on January 25, we will host VADM Jerome M. Adams, the current Surgeon General, for a Dean’s Seminar about the epidemic. Dr. Adams will be joined for this discussion by Dr. Monica Bharel, the Massachusetts Commissioner of Health, and by Dr. Jonathan Woodson, the Former Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs. Then, on January 31, we will host Dr. Sally Satel, Resident Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, and Consulting Psychiatrist at Partners in Drug Abuse Rehabilitation and Counseling Clinic. Dr. Satel will discuss the implications of the opioid crisis within the context of the social and cultural drivers of addiction. These events follow our opioid-related programming from late last year, when we hosted the inaugural summit of the Police Assisted Addiction and Recovery Initiative (PAARI).

In advance of these events, we are today running a modified version of the opioid Dean’s Note from last summer. We realize that we are placing a strong emphasis on the opioid epidemic, in both our publishing and our programming. We do so because this ongoing crisis has become, arguably, the defining public health issue of our time. In focusing on the opioid epidemic, we follow the principle of not letting the urgent crowd out the important, of keeping attention, always, on the deeper forces that shape health.

It is difficult to imagine now, but 10 years ago, opioids research received little attention or funding. It was considered a marginal issue, and efforts to address the growing crisis—for example, thorough the administration of naloxone—were slow to gain traction. That this once-neglected concern was allowed to become such a devastating challenge speaks to a core responsibility of public health—to monitor emerging pathologies, with an eye towards preventing them. The present scale of the opioid crisis argues as much for data-informed public health solutions as it does for vigilance against the emergence of new threats, so that we may stop the next epidemic, wherever it arises, from matching the dimensions of the opioid crisis.

Drug overdoses are currently the leading cause of injury death in the United States, ahead of motor vehicle accidents and deaths from firearms. Overdose deaths have increased more than six-fold since 1980. They are now the leading driver of all injury or accident death—and are fourth overall in terms of broad causes of death in the US, behind only heart diseases, cancer, and chronic lower respiratory diseases.

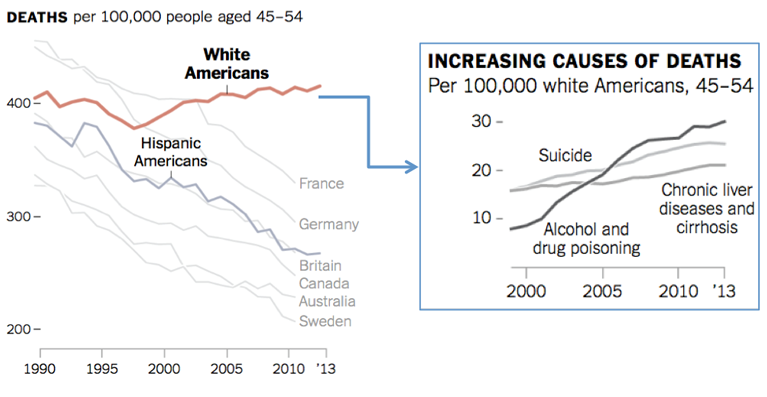

The overall impact of opioid deaths is being felt nationwide. Overdoses, which are primarily unintentional, are a major contributing factor to the recent decline in life expectancy among white, middle-aged Americans (Figure 1). The increasing death rate among this demographic, coupled with several recent high-profile overdose deaths, has captured the media’s attention in recent years, despite the fact that overdose rates had been increasing for decades across many different demographic groups.

Adapted from Kolata G. Death rates rising for middle-aged white Americans, study finds. The New York Times Health. November 2, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/03/health/death-rates-rising-for-middle-aged-white-americans-study-finds.html Accessed May 1, 2017.

The surge in overdoses has affected far more than middle-aged Americans. Young adults aged 18—24, for example, saw a 55 percent increase in hospitalizations related to overdose between 1999 and 2008, and the epidemic has affected people of all income levels.

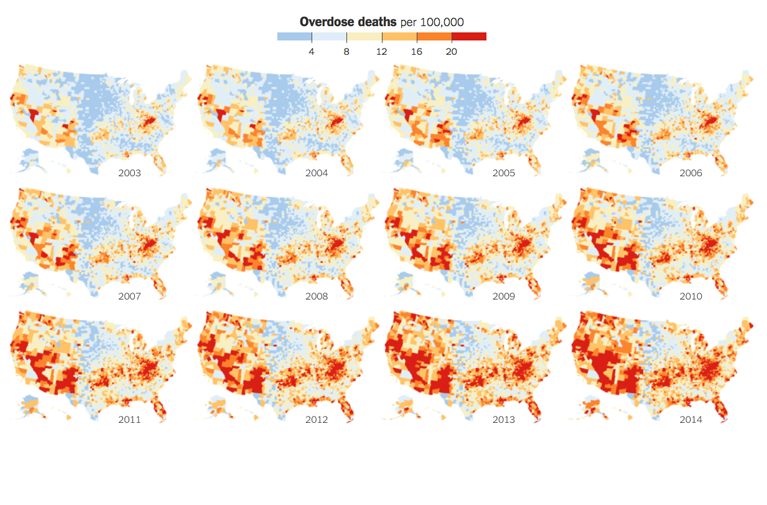

Geographically, the opioid epidemic has resulted in increased clustering of overdose deaths in rural areas across the US, particularly in Appalachia and the Southwest, which can be seen in Figure 2. This has changed the perception of a problem that had previously been viewed as a largely urban concern.

Park H, Block M. How the epidemic of drug overdose deaths ripples across America. The New York Times. January 19, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/01/07/us/drug-overdose-deaths-in-the-us.html Accessed May 1, 2017.

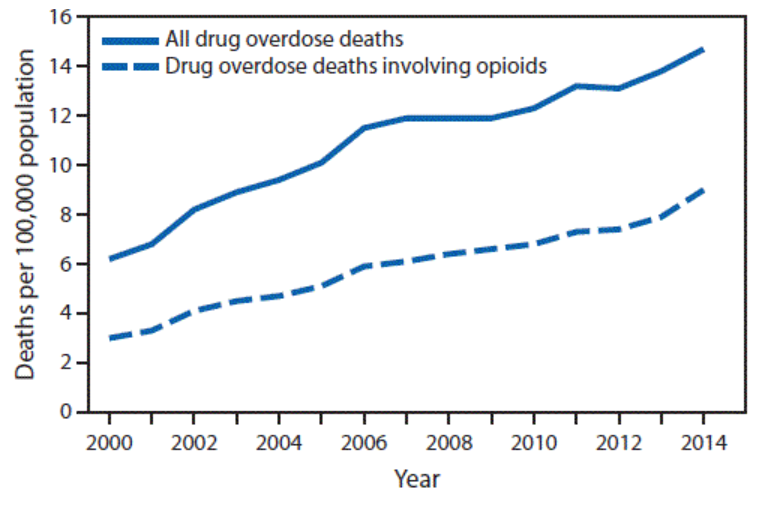

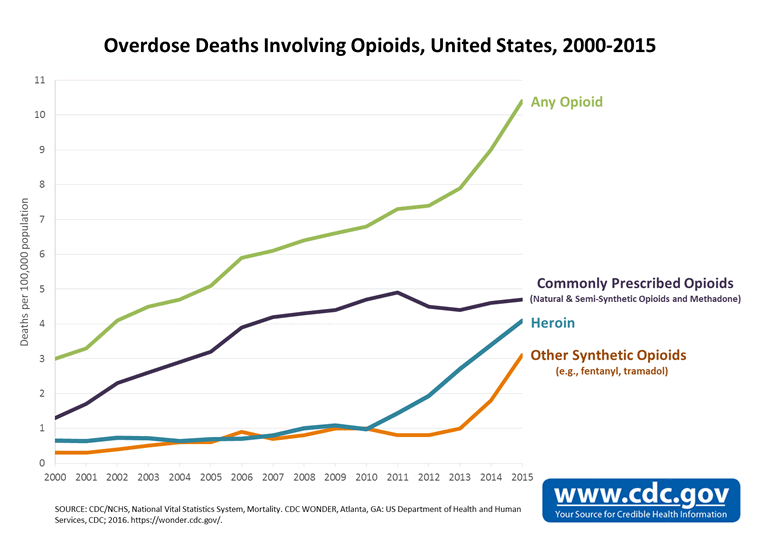

As shown in Figure 3, the recent increase in overdose deaths is driven largely by opioids, a class of drugs primarily used to reduce pain. Opioids range from commonly prescribed semisynthetic (partially natural) opioids such as oxycodone, to synthetic (human-made) opioids such as fentanyl and methadone, to illegal heroin.

Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden M. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000—2014. MMWR. 2016; 64(50): 1378—1382. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6450a3.htm Accessed May 1, 2017.

The number of deaths involving opioids has quadrupled since the start of the century. Opioids contributed to more than 33,000 deaths in 2015, and about half of these deaths involved a prescription opioid. This number is expected to nearly double in 2016, demonstrating that the worst may still be yet to arrive.

Much of this rapid rise in opioid deaths was originally attributable to increased prescribing patterns. From 1999 to 2013, the number of prescription opioids dispensed increased rapidly; in 2013, there were enough opioid prescriptions written for each adult in the US to have a bottle of pills. It is important to note, however, that prescribing differs by race. For example, black patients are over 40 percent less likely to be prescribed opioids for back pain in the ER compared to white patients, which may be one reason why the largest increase in opioid deaths has been among white Americans.

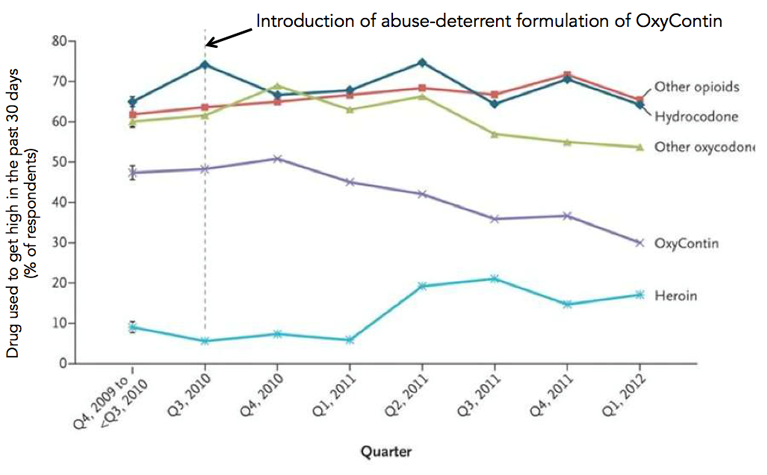

As the epidemic progressed, forces beyond prescription opioids have contributed to the increasing overdose rate. Restrictions placed on the prescribing of opioids—in response to the evolving epidemic—made it more difficult to obtain prescription opioids, occasioning a shift toward heroin use among a proportion of those who had become addicted to prescription painkillers. For example, after the introduction of an abuse-deterrent formulation of OxyContin, a commonly prescribed opioid, many users reported using more heroin and less OxyContin (Figure 4).

“America’s addiction to opioids: Heroin and prescription drug abuse.” National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2014/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse Accessed October 20, 2016.

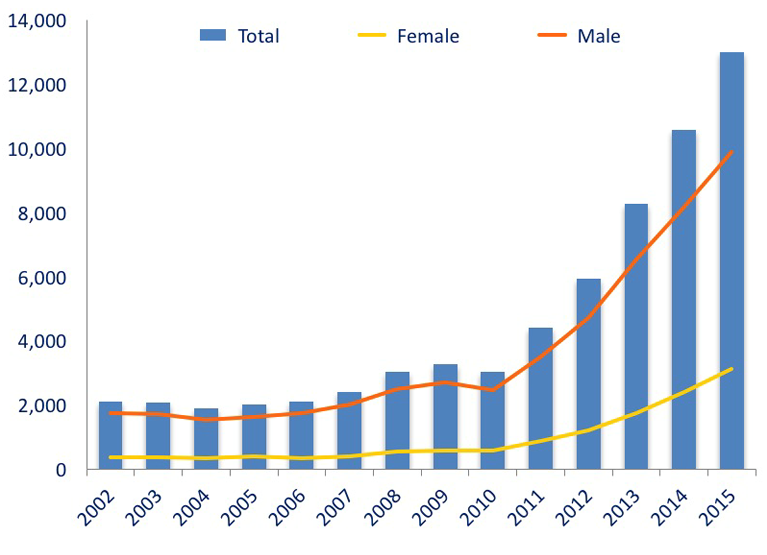

Figure 5 shows the six-fold increase in the national number of deaths from heroin alone from 2002—2015. The number of first-time heroin users reportedly roughly doubled between 2006 and 2013. Heroin is also often mixed with other substances, including cocaine, alcohol, and benzodiazepines, further increasing risk of death.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Updated January 2017. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates Accessed May 1, 2017.

Importantly, nationwide, it is fentanyl, a leading synthetic opioid, that has become the new and deadliest addition to the epidemic, as shown in Figure 6 below.

https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/analysis.html

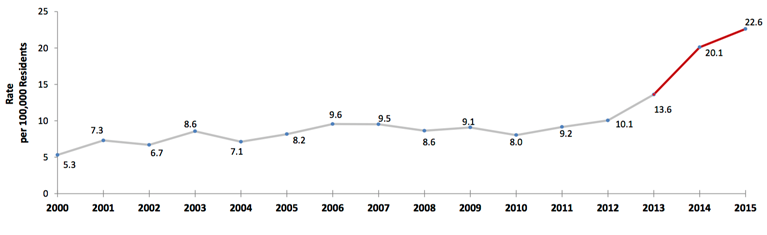

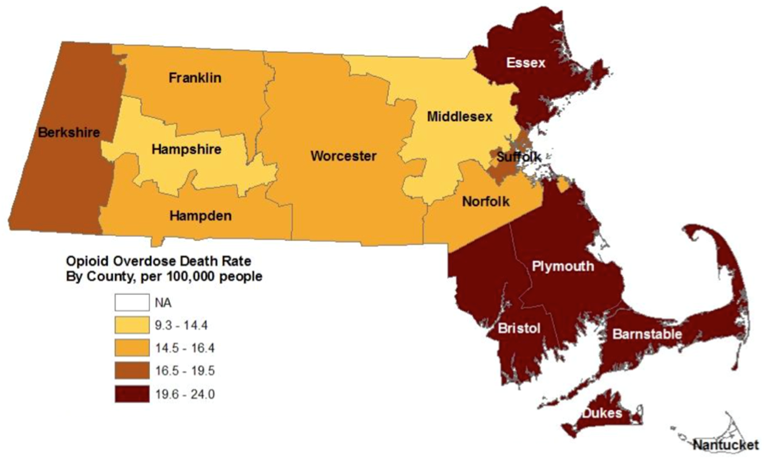

Here in Massachusetts, recent data largely matches national trends and risk factors, with the overall rate of opioid overdose increasing (Figure 7), particularly in rural areas (Figure 8), among those aged 25—44, and among those using more than one type of substance.

Massachusetts Department of Public Health, May 2016. http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/dph/quality/drugcontrol/county-level-pmp/data-brief-overdose-deaths-may-2016.pdf Accessed May 1, 2017.

Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Office of Data Management and Outcomes Assessment, August 2016. http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/dph/quality/drugcontrol/county-level-pmp/overdose-deaths-by-county-including-map-august-2016.pdf Accessed May 1, 2017.

In 2015, emergency personnel in Massachusetts responded to 11,884 opioid-related incidents, almost double the number of 2013. Naloxone, an opioid reversal medication, was used in the majority of these incidents, and had to be administered more than once in about a third of cases due to increasingly widespread introduction of fentanyl into the heroin supply. Among opioids, oxycodone was the most common drug present in toxicology results from 2013—2014, and most decedents had matching prescriptions for this drug within the previous three years.

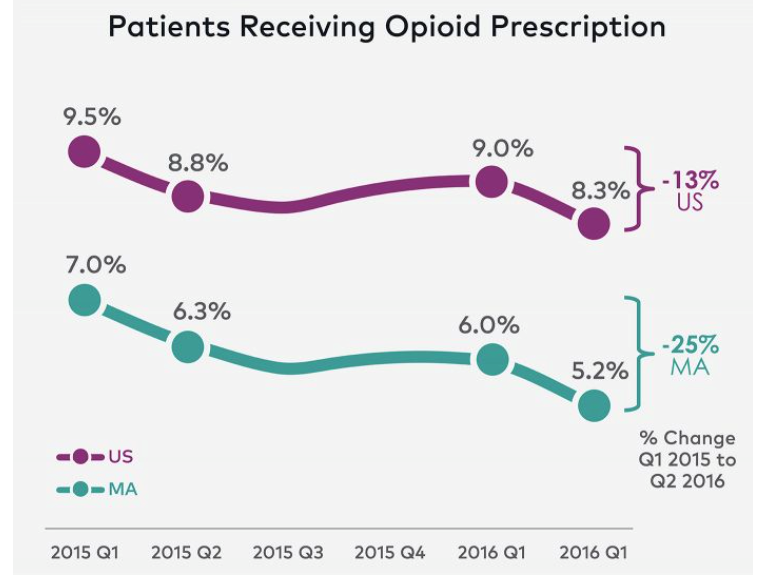

There have been recent steps taken to try to curb the epidemic, at the national, state, and local level—as a result. A year ago, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker signed An Act Relative to Substance Use, Treatment, Education and Prevention, primarily in order to strengthen prescribing laws and increase preventive education in the state. The law passed unanimously, and has many provisions, including a seven-day limit on first-time opioid prescriptions, enhancements to the Prescription Monitoring Program, prescriber training, expanded education programs, and mandated drug disposal programs. Although the longer-term effects of the bill will take years to measure, preliminary analyses have shown that the number of opioid prescriptions filled over the past year have fallen at a faster pace in Massachusetts compared to the national rate, as can be seen in Figure 9; public health practitioners in the state are therefore hopeful that overdose death trends should reverse. In addition to the recent bill, Governor Baker and the Department of Public Health also launched in 2015 an $800,000 media campaign to raise awareness of addiction and overdose.

Rice C. Massachusetts opioid prescription rates are falling. Data Insight, athenainsight. July 6, 2016. https://insight.athenahealth.com/mass-opioid-prescriptions-falling-faster/ Accessed May 1, 2017.

Several states, in addition to Massachusetts, have recently passed legislation to set prescribing limits, and aim to improve monitoring databases in order to curtail “doctor shopping.” Many individual states have also passed legislation to expand use of naloxone, which was approved decades ago and has been distributed to lay responders in many community-based programs since the mid 1990’s. Most drug users are likely to witness another drug user overdose at some point in their lives, and the majority report that they would be willing to administer naloxone to another user in the event of an overdose.

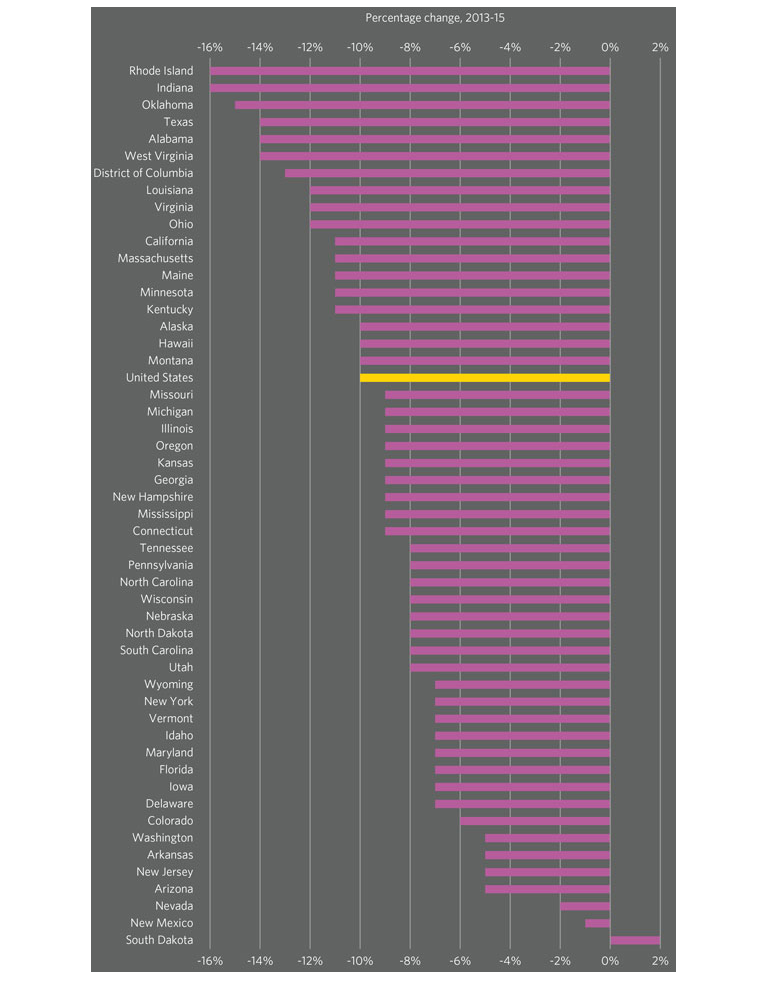

Taken together, these changes have largely shown promising early results in physician behavior. The national rate of opioid prescribing dropped 10 percent between 2013 and 2015, and decreased in every state except for South Dakota, as shown in Figure 10.

Vestal C. In some states, resistance to new opioid limits. June 28, 2016. The Pew Charitable Trusts: Research & Analysis: Stateline. http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2016/06/28/in-states-some-resistance-to-new-opioid-limits Accessed May 1, 2017.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently released guidelines for prescribing opioids. These guidelines suggest that opioids should not be among first-line therapies for chronic pain, and instead should generally be reserved for cases of active cancer and end-of-life care. When prescribed, opioids should be used for very short-term care after surgery or injury, preferably with shorter-release, in lower doses, and combined with other types of therapy.

Concluding, I note that we have a long tradition of excellence in research in this area, with faculty members such as Professors Richard Saitz, Jeffrey Samet, and Michael Stein having made important contributions to this literature. In addition, Boston Medical Center recently received a $25 million gift to create an addiction center here on campus, which now operates under the leadership of former Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy Michael Botticelli. There remains, of course, much to be done, and it is indeed appropriate that we engage with this issue until we can fully mitigate the extent and consequences of the opioid epidemic.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Robert A. Knox Professor

Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Laura Sampson and Professor Michael Stein for their contributions to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/tag/deans-note/