Surf Music

R. Sam Deese is a historian by day, bard by night

Masterpieces can land on the page or canvas in a flash. At the end of his life, Vincent Van Gogh averaged a painting a day; Anthony Burgess wrote A Clockwork Orange in less than a month. But sometimes a work of art needs to gestate. Margaret Mitchell spent 10 years writing Gone with the Wind; Kanye West says it took him 5,000 hours to write his platinum hit “Power.” When it comes to creativity that unwinds rather than explodes, poet and historian R. Sam Deese has Mitchell and West beat—by about 20 years.

Deese, a lecturer of social sciences at CGS and of history at BU Metropolitan College, is the author of Surf Music (Pelekinesis, 2017), a collection of poems National Book Award–winning poet David Ferry calls “a cascade of observation and pleasure.” Deese wrote the collection’s 81 poems over 30 years. Some are short: “Road Runner” zips by in five lines, ending (how could it not?) with a playful “meep, meep.” Others linger: the fantastical tales of “Nine Songs For The Mirror & The Monkey” span 10 pages, weaving together kings, priests, and baboons and taking readers “over scorching flats / Through mazes thickly twined.” In late July 2017, Deese read from Surf Music at the New York City Poetry Festival.

In his academic job, Deese (GRS’95,’07) is an expert in 20th-century world history and the author of We Are Amphibians: Julian and Aldous Huxley on the Future of Our Species (University of California Press, 2014), a study of the two brothers and their ideas about ecology, evolution, and progress.

Surf Music is about none of those things. And, despite the title, “there’s nothing about the Beach Boys in any of these poems,” he says. But the influence of Deese’s childhood home, California, extends beyond the title page.

His poetry is rich with descriptions of the West, particularly the region’s developed areas, “whether it’s freeways or parking lots or jet planes or people leaving the movies,” says Deese. Nature, technology, and sound “unite probably most of the poems in the book, but not all of them.” Because the poems are held together by these thin threads—echoes from verses that might have been penned 30 years earlier—and not bound by a single restricting theme, the reader is granted the freedom to create their own connections: “If ignorance is bliss, / It’s nothing next to this: / The warm, narcotic glow / Of what we think we know.” (“If Ignorance is Bliss”)

The Cautionary Tale of Lord Byron

Although Deese studied poetry with Professor Robert Pinsky and former professor Rosanna Warren in BU’s Creative Writing Program, he never considered making a career out of it. Poetry is his luxury. He makes time for his academic writing—a new book on climate change and democracy is in the works—but poems just come along “when I feel like it.”

“I like the Chinese model of the Confucian gentleman who takes care of practical matters and then writes poems here and there,” he says. “Every time I hear the word ‘poet,’ it makes me wince a little bit because I think of Lord Byron, where it’s a totalizing, not just profession, but calling or destiny.”

less the sound

of engines running

than the sound of air,

embracing and releasing

something on its way

to somewhere.

—“Surf Music”

Being a published poet places Deese among a vibrant community of creative writers at CGS. Regina Hansen, a master lecturer of rhetoric, writes for children’s magazines; Robert Wexelblatt, a professor of humanities, has published scores of books and creative essays (a list of his publications spans 19 pages); Meg Tyler, an associate professor of humanities, is a poet with a published collection. Deese suspects it’s because the College attracts generalists, professors comfortable teaching in different fields and setting joint assignments with specialists beyond their areas of expertise.

“It’s really important that our society continues to nurture generalists because somebody has to be looking at the big picture,” he says. “Often when people specialize, they know more and more about less and less.”

One of Deese’s fellow authors at CGS, Megan Sullivan, says she’s not surprised that so many of her colleagues publish outside of professional journals. An associate dean and associate professor of rhetoric, she’s the author of meticulously researched books on subjects such as the impact of parental incarceration on families—and an illustrated children’s book, Clarissa’s Disappointment (Shining Hall, 2017).

“People who teach in general education often want to reach diverse readers; they are as comfortable writing for a specialized academic journal as they are for a local newspaper,” says Sullivan. “The venue is almost irrelevant; the point is to engage with others.”

Her children’s book taps into an area of her research expertise—it’s the story of a child with an incarcerated father—but she says it was exciting to reach across genres.

“For me, although academic writing and writing for children present different challenges, these challenges are not onerous, and they allow me to stretch myself as a writer. I have never entirely seen a distinction between creative writing and academic writing, because there is a kind of creativity in both.”

Sculpting a Poem

There are few similarities between the tone and content of Deese’s academic and creative writing, apart from a tendency to write long and cut back. “If there’s a tension in my life, it’s between the brevity of lyric poetry and the discursiveness of historical writing,” he says.

The relative conciseness of his poetry echoes the work of his father, Rupert, a sculptor whose creations are displayed in institutions such as the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“My father was an incredible craftsman and his work was often austere and I certainly admire that,” says Deese. “I think if I write something—a poem—if I feel like I’ve really got it, it’s because I’ve cut away everything that’s not necessary and gotten down to the bare bones of it, and that was kind of my father’s aesthetic style. Boy, I don’t know if he would agree with that, but that’s how it strikes me.”

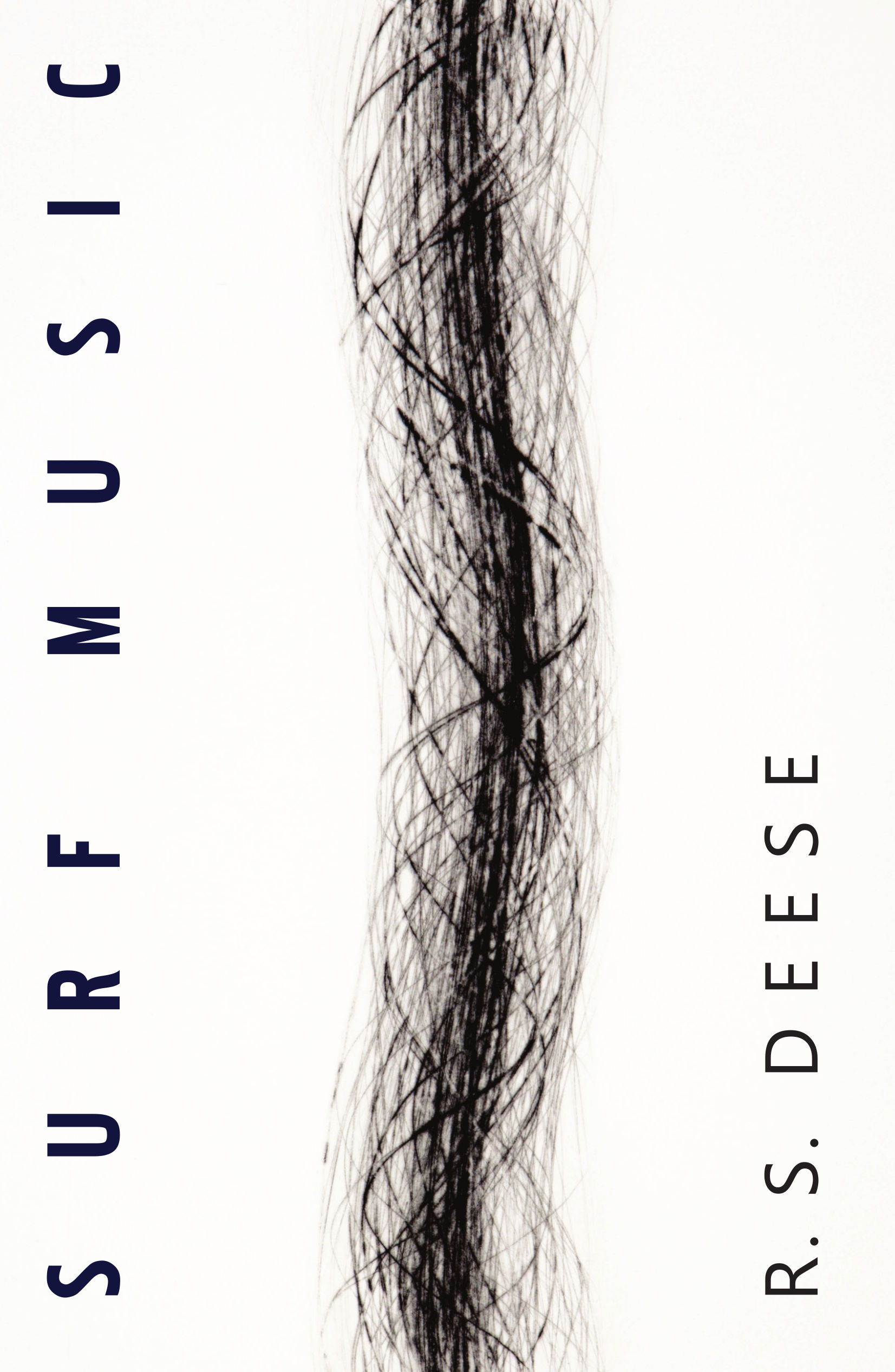

Surf Music started as a literal work of art. The first iteration was published as a limited edition, with nine poems by Deese and nine prints stamped out from linoleum by one of his brothers. The same brother, also named Rupert, created “Aphros,” the drypoint print on the cover of the 2017 edition of Surf Music.

Despite the artistic influences weaving through his life—another, his wife, the writer Isadora Deese (GRS’94), scrutinizes all of his work—a more practical inspiration pointed Deese toward teaching. His mother taught English at the University of California, Riverside, and “it seemed like a reasonable job,” he jokes. “Looking at the two jobs of my parents, I figured teaching was something I could comprehend more than what my dad did.” Not a poet then, but a teacher who writes poetry.