From the Archives of an SPH Alum.

Ghulam Nabi Kazi outside his South Huntington Avenue apartment as a Green Line streetcar goes by in 1997. Photo courtesy of Ghulam Nabi Kazi.

From the Archives of An SPH Alum

Ghulam Nabi Kazi (SPH’97), a Pakistani physician turned international civil servant, shares photos from his days at SPH in the late ’90s and reflects on the lessons he has learned over the course of more than three decades in the field of public health.

After a career in public health spanning more than three decades across three continents, Ghulam Nabi Kazi (SPH’97) realized that many outcomes in public health depend on behavioral change, and that is one of the most difficult changes to bring about.

“You have to persevere, you have to be patient—you cannot expect anything in a jiffy,” says Kazi. “Things will take time to materialize. You have to work for every inch, every step, every 1% of change in indicators. Any improvement you want to bring about, it will not be easy.”

Kazi was a successful hospital administrator and dermatologist at one of Pakistan’s largest teaching hospitals prior to coming to the United States to study at the School of Public Health. After earning his MPH, he spent nearly 15 years with the World Health Organization (WHO) working on tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, mental health, and the social determinants of health in Pakistan and South Sudan. Along the way he amassed a wealth of expertise on the development, planning, and operations of public health projects in low- and middle-income countries and developed a perspective on public health that, as he puts it, takes into consideration the inevitable influence of the “political determinants of health” in these countries.

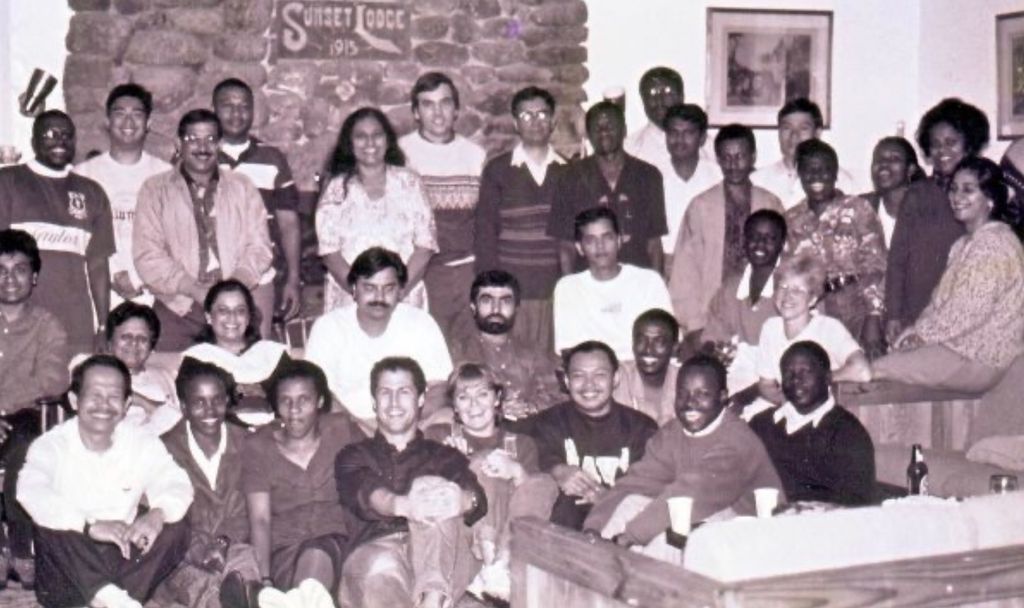

Assistant Professor Mike Trisolini with participants of the Financing Healthcare in Developing Countries course during a retreat to Cape Cod in 1995.

Financing Healthcare in Developing Countries course retreat, Cape Cod 1995.

There’s a difference between public health and other disciplines, says Kazi. “One of the rules of the bureaucracy is, ‘Don’t touch a file until it becomes a burning issue,’ [and] by the time someone touches the file, the problem is solved already. That doesn’t happen with us. In public health, it’s like there’s a brick [with] one drop [of water] falling on it constantly. Now, one day, the brick might break up—it could take one year, it could take five years, it could take 30 years, or it may not break up. Despite having the funding and putting in the effort, you may not succeed.”

Perhaps that is why Kazi, though now formally retired, has hardly slowed down.

Since January 2022, he has served as editor-in-chief of Public Health Action, a journal of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, leading the journal’s strategic focus on global health issues that align with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Kazi also serves as board chair and chief operating officer of Kaizen Strategic Consultants, which focuses on the development of national strategies for nursing and midwifery education in Pakistan, and as a senior adviser for research and development at the DOPASI Foundation, which conducts tuberculosis (TB) control and health systems strengthening projects, including research on COVID-19 variants. When he is not editing, consulting, or advising, Kazi enjoys mentoring Master of Global Health students from the University of Milan.

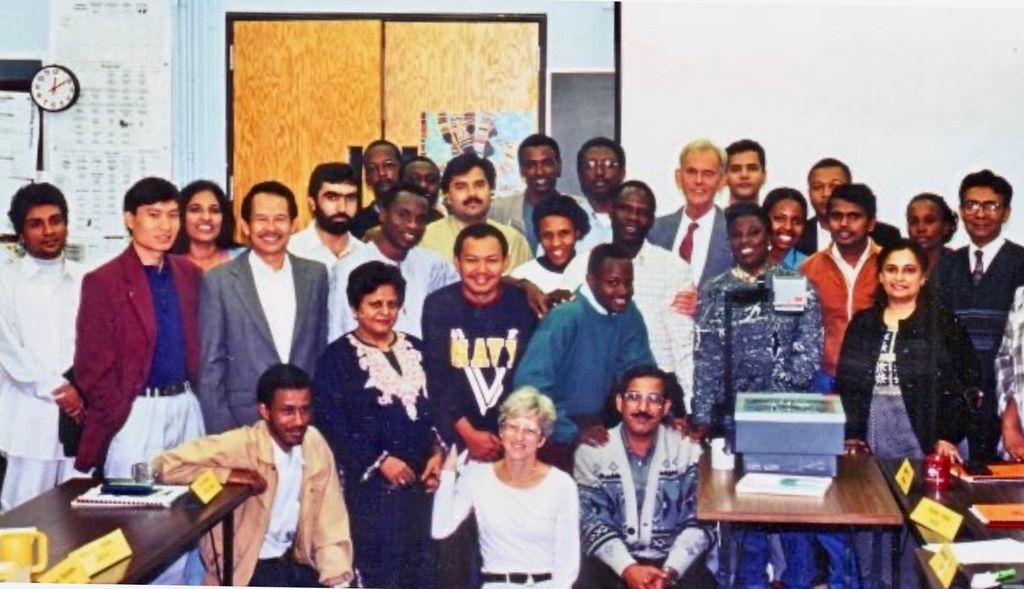

The Financing Healthcare in Developing Countries course class of 1995 with Brian Abel-Smith, professor emeritus at the London School of Economics, at the conclusion of his series of lectures in September 1995. M. A. Jama (later Assistant Director General, WHO) stands to his left in the back row. Abel-Smith died of cancer on April 4, 1996; thus, this was perhaps his last lecture at SPH. Earlier, he advised 50-60 countries, the World Health Organization, the International Labor Union, and the World Bank on health economics, health systems, and social welfare systems.

Kazi’s mentees remind him of himself when he made his first foray into the field of public health in the early 1990s. Pakistan’s secretary of health recruited him from the administrative ranks of Civil Hospital Karachi. Kazi accepted the secretary’s invitation and began supporting the planning and development of a family health project funded by the World Bank.

The project, he recalls, launched on the heels of a monumental World Development Report titled “Investing in Health,” which introduced for the first time a methodology to estimate the global burden of disease using disability-adjusted life years or DALYs, thus enabling the attachment of financial value to public health interventions. Kazi, having some training in health economics and keen to excel in his new role, used the support of the World Bank to enroll in a course on financing health care in developing countries at the School of Public Health in 1995.

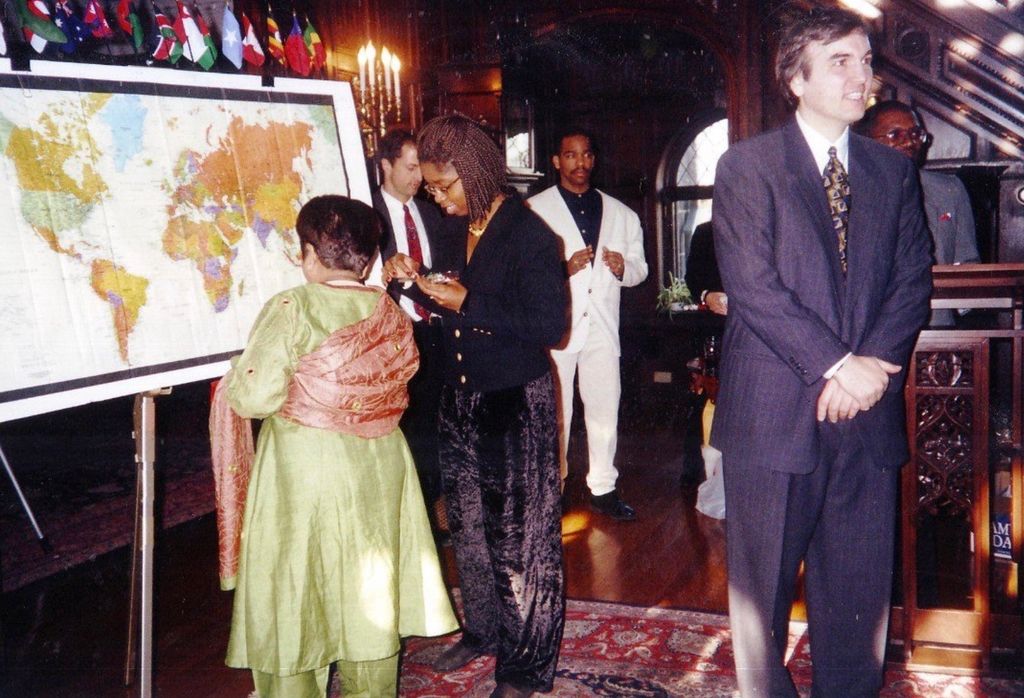

Assistant Professor Michael Trisolini addresses graduates of the Financing Healthcare in Developing Countries course. Mike Devlin and Saroj Bala Chada are seen in the background. Graduates mark their countries on a world map.

Ghulam Nabi Kazi holds M.A. Jama’s son, alongside a faculty member, Joe, and Madhu Sood from India.

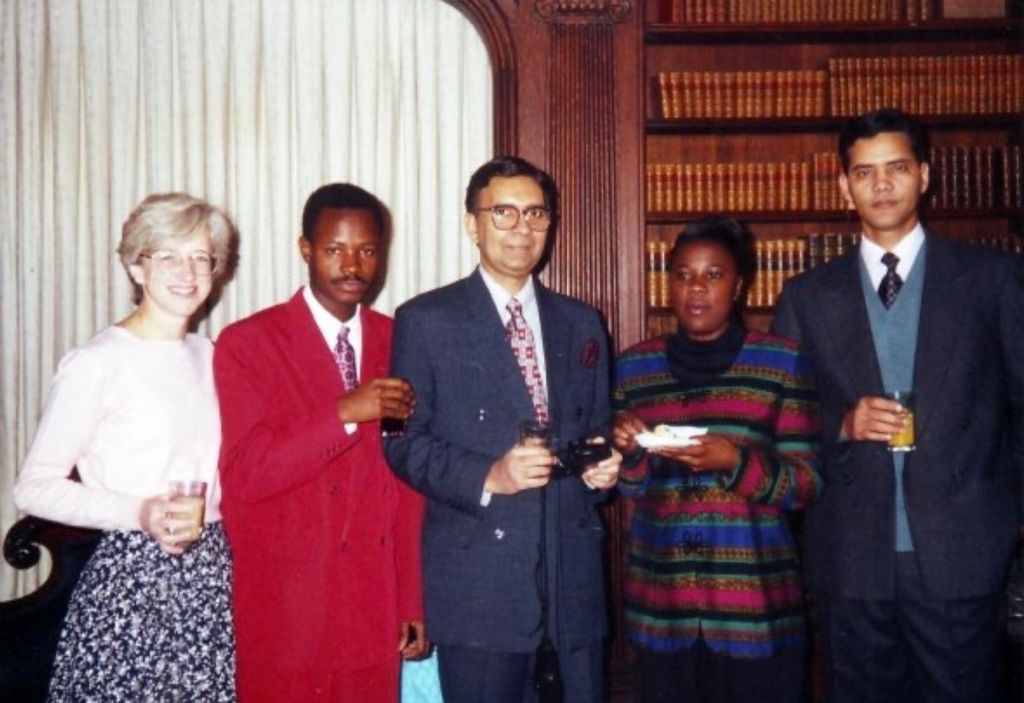

Graduates celebrate completion of the course, December 1995. From left: Sheila Purves (would go on to earn Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire for her work), Bamoussa Coulibaly, Ghulam Nabi Kazi, Esther Ngoi, and Hadramy El-Ducros.

Ghulam Nabi Kazi (second from left) with his wife Khowla (left) and classmates—Bamoussa, Pathi, and Ariana—during their graduation at the BU Castle, December 1995.

Kazi thrived at SPH, surrounded by equally eager scholars from around the world. His warm memories of his classmates and professors are as sharp today as if he were a student just last summer. Snapshots from his Boston years live in a public online archive with various other photos from his career.

After completing the finance course at SPH and returning to Pakistan to resume his work, Kazi found funding to continue his studies and again, he and his wife moved to Boston.

During his time on campus, Kazi leaned into his passion for writing. His favorite professor was Lucy Honig, who won 1992 and 1996 O. Henry Awards for short fiction and taught academic writing at SPH during that time. He remembers a classmate once commented that by improving the clarity and flow of her student’s papers, Honig was contributing more to public health and global health than the students themselves.

Ghulam Nabi Kazi with his wife Khowla after securing his MPH, May 1997.

The BUSPH Graduates of 1997 from all concentrations pose for a group photograph, May 1997.

“Because when you start writing, [the] first draft is so dense that it’s hard to navigate through it. [As] it becomes simpler, then you start understanding what you’re writing yourself and you think of the reader and what everyone else thinks,” says Kazi. He briefly held a job as a ghost writer for academics before ultimately returning to Pakistan to resume his work with the department of health.

For Kazi, writing and public health have long complemented one another. As a contributor to the Daily Times, an English-language newspaper based in Pakistan, Kazi often reflects on valuable lessons he has learned from his experiences in global health and public policy. Ever the documentarian, he is also active on LinkedIn where he posts about his work and connects with other SPH alumni. With a growing number of alumni, and now a dean, from South Asia, Kazi hopes to one day host an SPH reunion in Pakistan.

Next year is SPH’s 50th anniversary and the Office of Marketing and Communications aims to celebrate the School’s history and legacy by highlighting the reasons behind why we do what we do, such as educating students so that they may become lifelong public health stewards like Ghulam Nabi Kazi. If you are an alum with photos or stories to share, we want to hear from you! Get in touch with our colleagues in Alumni Relations by completing out the following form: bu.edu/sph/alumni/sph50-spotlight-alumni-and-friends/