Veterans’ Health.

Our national attention to the health of veterans tends to waver, with periods of focus offset by longer periods of neglect. Our School, with an unusually close link to Veterans’ Affairs (VA), has long been deeply involved in issues regarding veterans’ health. At an individual level, I have had the privilege to work with service members and veterans for nearly 10 years now. This has resulted in a body of scholarship concerned with documenting the mental health consequences of military exposures and with identifying ways to improve mental health in this population. During the past year, I also was involved in editing the annual special issue of Epidemiologic Reviews, which this year focused on veterans’ health. The issue provides a useful compendium of articles about key issues concerning the health of veterans. Here I briefly summarize key concerns when thinking about health of the veteran population in an effort both to surface health of a frequently overlooked population and to stimulate our collective conversation.

Our national attention to the health of veterans tends to waver, with periods of focus offset by longer periods of neglect. Our School, with an unusually close link to Veterans’ Affairs (VA), has long been deeply involved in issues regarding veterans’ health. At an individual level, I have had the privilege to work with service members and veterans for nearly 10 years now. This has resulted in a body of scholarship concerned with documenting the mental health consequences of military exposures and with identifying ways to improve mental health in this population. During the past year, I also was involved in editing the annual special issue of Epidemiologic Reviews, which this year focused on veterans’ health. The issue provides a useful compendium of articles about key issues concerning the health of veterans. Here I briefly summarize key concerns when thinking about health of the veteran population in an effort both to surface health of a frequently overlooked population and to stimulate our collective conversation.

Veterans and Service Members, Past and Present

In the United States in 2015, there were approximately 2.3 million active military service members, including 1.43 million active duty personnel and 855,000 reservists. As of 2014, there were an estimated 22 million veterans. A major change in recent US military operations, particularly in the recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, resulted in a move toward greater reliance on the reserve component, including the National Guard and Reserves. Another major shift seen is the health focus in battlefield care from mortality to morbidity, based on both technological advances in battlefield medical care and changes in combat engagement. Whereas the wounded to killed ratio was about 3 or 4 to 1 in the Vietnam war, it was approximately 10 to 1 in the Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), and Operation New Dawn (OND) conflicts. This has resulted in substantially lower deaths among military personnel compared to previous conflicts, but also, commensurately, with more injured military personnel and veterans.

Physical Health

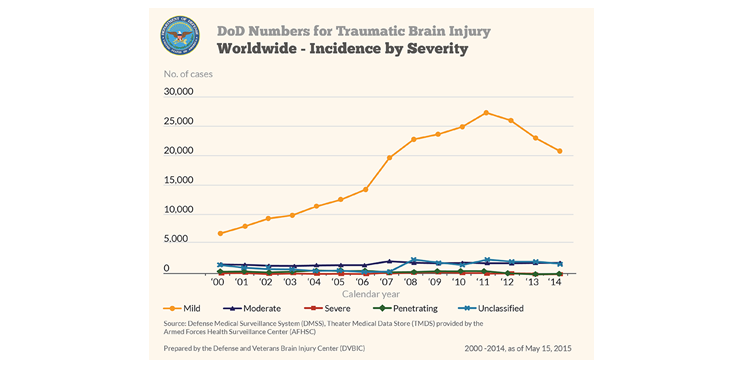

The most common class of conditions among veterans utilizing VA healthcare (56.3 percent), suggestive of the prevalence of the conditions among the veteran population, is musculoskeletal issues; chronic pain continues to affect approximately half of returning service members. Appropriate management of pain remains a clinical and health care systems challenge, as providers strive to move away from a sole reliance on opioid therapies, which carry serious safety risks, and toward interdisciplinary approaches. Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), while not as common, is considered the “signature wound” of veterans returning from the OEF/OIF/OND conflicts. Mild TBI comprises the vast majority of recorded TBI among military service members (see Figure 1), and has an estimated prevalence of 20 percent in this population.

Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center

Mild TBI is associated with symptoms that are cognitive (e.g. memory problems), somatic (e.g. headache), and affective (e.g. mood changes) in nature. Even mild TBI can be associated with functional impairment in social and occupational roles. TBI is often comorbid with PTSD, and they have many shared symptoms, making studies of etiology and interplay challenging. Veterans exposed to improvised explosive device blast injuries may experience a comorbid presentation of TBI, PTSD, and musculoskeletal injury. A not insubstantial proportion of returning veterans have injuries to multiple body parts and organ systems, typically referred to as polytrauma, and the VA has carved out a coordinated set of services for such individuals. Although physical injury has, historically, been perhaps the most visible wound of war, increasing evidence suggests that the burden of mental illness among service members and veterans may dwarf the burden of physical illness.

Mental Health

Exposure to a range of potentially traumatic events is a common experience among military forces and civilians alike, and mental health and re-adjustment challenges are common among service members returning from deployment. Studies with population-based samples of returning service members have estimated that between 20 percent and 43 percent are in need of mental health services, while samples of veterans connected to VA healthcare indicate that about half are in need of mental health services. Estimates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among those who served in OEF/OIF/OND range from about 5 percent to 20 percent, while estimates of depression range from 2 percent to 16 percent. With greater reliance on the reserve component have come questions as to whether reservists face a greater burden of psychiatric problems relative to active duty component service members. While reservists do indeed have a unique set of post-deployment needs, they do not appear to have a greater burden of depression or PTSD on average. In contrast, reservists (15 percent) have a higher prevalence of alcohol use disorders on average, relative to their active duty counterparts (9.9 percent).

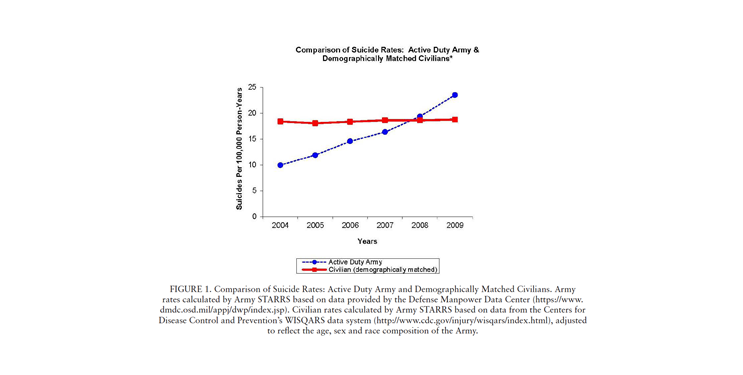

Suicide has been cause for substantial concern among military service members and veterans during these recent conflicts. While the suicide rate among service members had been about half that of civilian counterparts before the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, there was a sharp uptick between 2005 and 2006. The suicide rate in the Army and Marines then nearly doubled between 2005 and 2009. As shown in Figure 2 below, in 2009 the rate of suicide in the active duty Army surpassed that of demographically matched civilian counterparts. Suicide is a rare and difficult to predict outcome, and puzzlingly does not appear to be linked to deployment among those who served during the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Nock, M. K., Deming, C. A., Fullerton, C. S., Gilman, S. E., Goldenberg, M., Kessler, R. C., … & Ursano, R. J. (2013). Suicide among soldiers: a review of psychosocial risk and protective factors. Psychiatry, 76(2), 97-125.

Of note, a recent study found that non-deployed soldiers had a higher prevalence of pre-enlistment mental health disorders than age-matched civilian counterparts. Together with another recent study finding elevated risk of prior childhood maltreatment among veterans of recent wars, this evidence suggests that selection factors may be driving the rising tide of mental health diagnoses.

Treatment via Department of Defense and Veterans Affairs

Despite services provided by the VA and the Department of Defense, returning service members face many challenges in receiving mental health care. Barriers include stigma and personal beliefs about mental illness. Population-based samples estimate that approximately 50 percent of military service members in need of mental health treatment receive care, while only 30 percent receive minimally adequate care. A recent VA study estimated that more than half of VA enrolled veterans in need of care waited more than two years to access mental health care, and that there was an additional seven and a half years lag time on average to receipt of minimally adequate care. A recent Institute of Medicine report that I led examined treatment of PTSD in returning veterans and came to the conclusion that while both the VA and the Department of Defense (DoD) have committed financially and programmatically to treatment of PTSD, “a lack of standards, reporting, and evaluation significantly compromises these efforts.” Substantial new efforts are being invested by VA and DoD to help overcome some of these challenges.

Women’s Health

Recent conflicts have seen a five- to seven-fold increase in the prevalence of women serving in the military relative to the Vietnam War, as well as a major expansion in the breadth of their occupational roles, including combat support and, recently, direct ground combat in the Army. Both the VA and DoD offer women’s health care services, although many challenges remain in ensuring access and adequate utilization of services among women. Military sexual trauma is disproportionately faced by women, appears to affect approximately one in five females, and continues to require a shift in military culture and operations. While the study of women’s health in the military is relatively nascent, the rapid growth of the number of women in military roles suggests an urgent need for both scholarship and effective interventions in the area.

Our Role

There is little question that a world without war is a better world. There is also little question to my mind that we shall not, in our lifetimes, see such a world. Until that time comes, we as a country have a particular duty to ensure that the health of those who we send in harm’s way is preserved and protected. It is therefore the role of public health scholarship to document the health of our military and veteran populations, to ensure that our students are educated on health of this population, and to engage in translating our knowledge to the end of generating opportunities to promote health of veterans. Our School has a long tradition of close linkages with the VA; these linkages have allowed us to be at the center of some of the most exciting scholarship in this area, and we have seen our faculty make seminal contributions. I look forward to deepening and strengthening this work together in the coming years.

I hope everyone has a terrific week. Until next week.

Warm regards,

Sandro

Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH

Dean and Professor, Boston University School of Public Health

Twitter: @sandrogalea

Acknowledgement: Gregory Cohen, MSW, contributed to this Dean’s Note.

Previous Dean’s Notes are archived at: https://www.bu.edu/sph/category/news/deans-notes/

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.