Global Christianity as a Dynamic Conceptual Tool

Global Christianity or World Christianity is a useful conceptual tool to better understand Christianity as a global religious phenomenon. As the term emerged in theological and academic circles, it has meant different things in different contexts. The concept itself is often a mixture of theological ideal and scholarly framework.

Global Christianity or World Christianity is a useful conceptual tool to better understand Christianity as a global religious phenomenon. As the term emerged in theological and academic circles, it has meant different things in different contexts. The concept itself is often a mixture of theological ideal and scholarly framework.

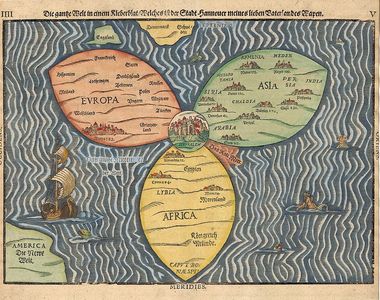

In theological circles, World Christianity reflects two key normative claims: that at its core Christianity is missional and globally oriented, and despite differences across communities, Christians are a loose family, united in adherence to one Lord, Jesus Christ. In scholarly circles, the concept of World Christianity reflects a move to interpret Christianity from a global perspective. To use a visual metaphor, both circles attempt a shift in focus, to press ‘zoom out’ on a camera lens to a global view of Christianity as a religion found in all continents and adapted to a myriad of cultures. From its inception it is understood as a multifaceted religion capable of crossing geographic, linguistic, and cultural boundaries. With a lens zoomed out to a global view, Christianity can no longer be seen as a ‘western’ religion. Indeed, its demographic center of gravity is no longer in the West, but in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. A global perspective also urges scholarship and public discourse to pay more attention to branches of Christianity like the Oriental and Eastern Orthodox churches, and the new forms of Christianity in the ‘global south.’

This mix of theology and secular scholarship in the concept of World Christianity is dynamic and promising for both committed Christians and scholars (and if you happen to be both, that is even better – but I’m revealing my own bias). World Christianity as a malleable conceptual tool can allow local Christians, missionaries, and theologians the space for expression. Their perspectives are vital for understanding the way Christianity is lived and reflected upon on the ground. In this way, the contributions of practicing Christians can be taken seriously, not just as ‘data’ for religion scholars (following J.Z. Smith), but for their constructive additions to the field. Further, the concept of World Christianity can propel theologians, missionaries, and local leaders to make use of the tools that historians and social scientists use on Christianity. It also forces Christians out of their comfort zone of speaking in-house to like-minded believers and to join in on more secular conversations.

World Christianity will look very different in the secular religious studies school of Arizona State University and the theological halls of Princeton Theological Seminary. But neither a robustly theological or a secular orientation can fully ignore each other. World Christianity can blur and redraw lines between them. To give an example, of the two institutions just mentioned, ASU’s recent hire of an assistant professor of Global Christianity is a graduate of Princeton Seminary. As a conceptual frame, World Christianity can be rearranged and deployed in two contextual languages, include many more voices, and produce enriched new scholarship. I believe that BUs Center for Global Christianity and Mission is among the places with success in accommodating both secular and theological impulses. For me, the interplay between theological and secular scholarship is part of the excitement of this budding field of World Christianity.

Eva M. Pascal

PhD Student, Graduate Division of Religious Studies