Research Update from Mary Lou Shea

Mary Lou Shea, Th.D.

October 30, 2012

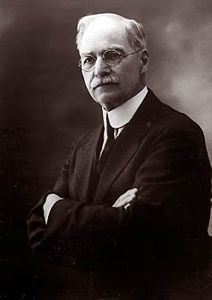

Just about one year ago, I began my research into the life and ministry of Hiram F. Reynolds, one of the founders of a Wesleyan-American Holiness denomination, the Church of the Nazarene. As a historian of Christianity with a strong interest, and background, in mission history, I was appalled at my own lack of knowledge about the man who was widely considered “Mr. Missions” by earlier generations of Nazarenes. As an educator serving at a denominationally-affiliated college, my ignorance was galling (to me, at least. Most of the current crop of twenty-somethings have never even heard of Reynolds, and their parents have only vague ideas about who he was and why he might have mattered to their parents and grandparents.) The denominational archivist, Dr. Stan Ingersol, had approached me several years ago at a conference, tempting me with the opportunity to be the first scholar to read the Reynolds collection. Ingersoll was insistent that Reynolds’s story must be told, and I seemed a likely candidate to do the telling. It has taken some time, and a self-funded sabbatical of sorts, but I have finally taken the plunge and spent the last thirteen months immersing myself in the life and ministry of H.F. Reynolds. (It seems, from having read his extensive correspondence, that the Rev. Reynolds was always and only “H.F” to everyone except his closest family. As such, while I have grown to admire and respect him, and even to feel a sort of filial affection, I am more comfortable referring to him as H.F. than as the more intimate “Hiram.”)

It has taken thirteen months of nearly constant work to feel that I have consulted the most important sources for one simple reason: Reynolds is an extraordinarily well-documented individual. He kept what appears to be most of the correspondence he ever received (or, at least, representative examples of every sort of correspondence.) He also developed the habit, early on in his tenure as a leader of the Church of the Nazarene, of making carbon copies of his out-going correspondence. As such, I was gifted with an estimated thirteen cubic feet of papers – and that may be a modest estimate. In addition, there are thousands of photographs taken by, and of, him. There are family albums, including an especially sweet and insightful one that formerly belonged to his granddaughter, Frances, whom he and Mrs. Reynolds raised from birth and later adopted. There are minutes of the various boards and meetings: the General Board of Foreign Missions, his baby for a quarter century; the Women’s Foreign Missionary Society; the General Board; the General Assemblies of the Church of the Nazarene; and more. There were the denominational publications, including the first twenty-six and a half years of “The Other Sheep,” the missions magazine and of “The Herald of Holiness,” a publication directed at the general population of the church; and almost as many issues of “The Beulah Christian,” the publication of the Association of Pentecostal Churches of America, with which Reynolds was associated prior to the foundation of the Church of the Nazarene. There were reports from the Annual Conferences of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Vermont, where Reynolds served as a pastor and evangelist for a dozen years at the beginning of his career. And, of course, there were the early denominational books about Reynolds – most of them written for youngsters, and many of them sounding suspiciously “inspirational,” and none of them boasting a single footnote! Reynolds himself wrote a book about his first round-the-world mission tour, which coincided with the outbreak of World War I and provided numerous thrilling adventures (including being aboard a German ship off the coast of southern Africa when war was declared. He ended up 3,000 miles off course and had to finagle his way across the Atlantic – twice – during the first months of the conflict.) Finally, Reynolds penned an autobiography while in his seventies. It was never published, although it did provide material for a popular biography written at the end of his life by Amy Hinshaw, who wrote similarly exciting stories about several of the more heroic Nazarene missionaries of the early years.

I have been delighted and relieved to discover, along the way, two important things. First, H.F. Reynolds has turned out to be a man possessing rare and important characteristics, including a healthy sense of humor; a deep and stalwart commitment to Christ and the church; a real knack for administration (including both a strong practicality and the astounding ability to listen closely to people); a genuine humility that made him approachable and encouraging to others who struggled along the way; and an enthusiasm for missions that combined with a willingness to invent or adopt approaches that made missions matter to everyone. I have been greatly relieved to discover that I like H.F. Reynolds. I would relish the chance to have him as my pastor, neighbor or brother-in-law. He is worth knowing, and I am honored to introduce him to his beneficiaries (both Nazarene and others) through the biography I intend to write, starting at the first of the year.

Second, I have been blessed by the professionalism, encouragement and generosity of the archivists and librarians with whom I have been privileged to work over these otherwise solitary months. Materials have been loaned, dug out of archival stacks, and hunted down through library networks. I have been given dedicated research space, assistance with photocopying and scanning, ready audiences when I have stumbled across something especially riveting or entertaining, and pep talks when I have been bleary-eyed. (I have discovered something about myself. I am good for no more than 52 issues of a newspaper or magazine, of 32 pages each, in a single day of reading. If the material is on microfilm, I may not quite make even that goal.) Scholarly research is often lonely, and sometimes confounding, and I suspect that, without the generous support of those who safeguard and share our documents, it would be impossible.

I am now the proud (?) owner of a stack of binders, full of research notes, that is roughly the size of my living room couch. I begin to realize that this assignment is rather more like my dissertation than I had imagined . . .just when one feels that one has scaled to the mountain top, it becomes apparent that those were only the foothills one was climbing. The Everest experience awaits. Happily, the climb will be in good company – H.F. and his stories will see me to the summit!