In Memoriam: James C. Scott (1936-2024) – A Dissident Voice in Political Science

When James C. Scott passed away on July 19, 2024, the academic world lost a maverick thinker who changed how we view power and politics. Farah Adeed – a PhD student at the Department of Political Science who works with Jeremy Menchik, Associate Professor of International Relations at the Pardee School of Global Studies – offers a personal take on Scott’s legacy in this piece.

Adeed’s own path – from Pakistan’s Punjab to Boston – echoes the kind of grassroots perspectives Scott valued. Now a Research Fellow at BU’s Institute on Culture, Religion and World Affairs (CURA), Adeed studies the interplay of religion and politics in South and Southeast Asia. This background gives him a unique lens to appreciate Scott’s boundary-pushing work.

In his tribute, Adeed doesn’t just remember a brilliant mind; he explores how Scott’s ideas continue to challenge and inspire students of global affairs. Drawing on his experiences as a former lecturer and journalist, Adeed bridges Scott’s theories with the real-world complexities of today’s political landscape.

For those unfamiliar with Scott’s work, this article serves as both an introduction and a farewell, highlighting why his approach to political science remains relevant for new generations of scholars like Adeed.

In Memoriam: James C. Scott (1936-2024) – A Dissident Voice in Political Science

Farah Adeed

Boston, USA

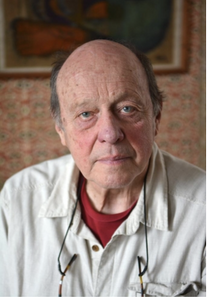

James C. Scott

We mourn the loss of James C. Scott, who passed away on July 19, 2024. Scott wasn’t just my favorite academic–he was a rebel with a cause in the world of political science. The rebellion was not just in his ideas but in his approach. He (rightly) challenged disciplinary boundaries and brought anthropological and historical insights into political science like a bull in a china shop. He reminded us that politics is not just about marble halls and fancy titles–it is about the messy, vibrant reality of human life.

Scott visited Boston University several times, particularly the Institute on Culture, Religion, and World Affairs (CURA), when it was under the directorship of Robert W. Hefner. Hefner, a professor in the Department of Anthropology and the Pardee School of Global Affairs, remembers Scott fondly. He notes that Scott was a rare breed of political scientist who valued ethnography for its ability to provide human contact and insight into real-world experiences. Scott’s interdisciplinary approach and his capacity to move seamlessly between different intellectual worlds left a lasting impression on colleagues like Hefner.

Scott’s work, in many ways, exemplifies what Edward Said (1982) advocated for in terms of crossing disciplinary boundaries. For instance, Said argues for “interference, a crossing of borders and obstacles, a determined attempt to generalize exactly at those points where generalizations seem impossible to make.” Scott’s scholarship, which blended insights from political science, anthropology, history, and other fields, embodied this approach. Similarly, Said called for intellectuals to “break out of the disciplinary ghettos in which as intellectuals we have been confined,” and Scott did just that by examining state planning through multiple disciplinary lenses. By bringing together diverse theoretical frameworks and types of evidence, Scott offers novel insights into the relationship between states and societies. This interdisciplinary approach allowed Scott to, as Said put it, “restore the nonsequential energy of lived historical memory and subjectivity as fundamental components of meaning in representation.” Scott’s attention to local, practical knowledge (what he termed “metis”) in the face of top-down state planning reflects Said’s call to open scholarship to “experiences of the Other which have remained ‘outside’…the norms manufactured by ‘insiders.’”[1]

The point I am trying to make is that in a field that often takes itself too seriously, Scott was the rebel who taught us to look for politics in the most unexpected places—in a farmer’s field, in a forester’s frustrations, and in the subtle art of dragging one’s feet.

Two of his groundbreaking works exemplify this approach:

- Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance (1985)

This book, based on Scott’s fieldwork in a Malaysian village, revolutionized our understanding of resistance and power dynamics. The chief argument is that open rebellion is rare, and instead, subordinate groups engage in everyday forms of resistance. He talks about discourses that take place “offstage” beyond direct observation by powerholders and identifies subtle forms of resistance such as foot-dragging, dissimulation, false compliance, pilfering, feigned ignorance, slander, and sabotage. This book challenges prevailing theories about peasant revolution and class consciousness and demonstrates how these small acts of resistance can cumulatively make significant impacts on power structures.

- Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (1998)

This work is a critique of top-down, state-initiated social engineering projects. Scott argues that centralized states, in their quest to make society “legible,” often simplify complex social practices to their detriment. He introduced the concept of “high modernism” – a belief in scientific and technical progress that can improve every aspect of human life. He analyzed failed state projects ranging from collectivization in Russia to compulsory villagization in Tanzania. Scott argued that local, practical knowledge (“mētis”) is often more valuable than abstract, generalized knowledge in solving real-world problems. He critiqued the simplification of natural and social systems for ease of state control and management.

Scott’s scholarship has shaped my understanding of power dynamics and resistance in Muslim societies. His work has encouraged me to look beyond overt political actions and to consider the political significance of seemingly apolitical behaviors. As a result, I find myself increasingly drawn to ethnographic approaches and trying to understand political phenomena from the ground up.

Let’s honor Scott’s memory by continuing to question our assumptions, look beyond the obvious, and seek to understand politics in all its messy, ground-level complexity.

Scott’s journey here has ended, but his legacy lives on!

[1] Said, E. W. (1982). Opponents, audiences, constituencies, and community. Critical Inquiry, 9(1), 1-26. The University of Chicago Press.