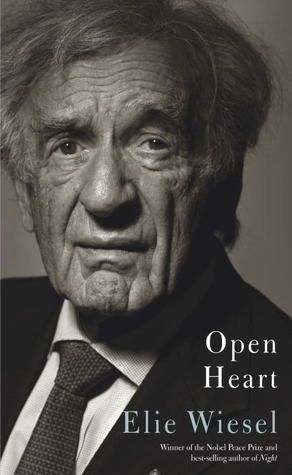

Elie Wiesel: A Retrospective, Week #10

In 2013, at the age of 82, Elie Wiesel unexpectedly had to undergo emergency open heart surgery. The procedure was successful and afterwards Wiesel explored his experience in a lecture that became this week’s text. It was to be his final book. The slim volume, Open Heart, provides an intimate portrait of Wiesel’s personality and family life in his later years. The selections we chose to share this week reveal his sense of humor in addition to his gift for poetic reflection.

In 2013, at the age of 82, Elie Wiesel unexpectedly had to undergo emergency open heart surgery. The procedure was successful and afterwards Wiesel explored his experience in a lecture that became this week’s text. It was to be his final book. The slim volume, Open Heart, provides an intimate portrait of Wiesel’s personality and family life in his later years. The selections we chose to share this week reveal his sense of humor in addition to his gift for poetic reflection.

Passage #1:

As soon as he receives his colleague’s message, my primary care doctor, a cardiologist, reaches me at home. On the phone, he appears to be out of breath; he speaks in a tense, emphatic voice, louder than usual. I have the feeling that he is trying to contain or even hide his nervousness, his concern. Clearly, he is unhappy to have to give me this bad news that will change so many things for me…

“I expected a different result,” he explains. “But now the situation requires some further tests immediately.”

“Yes?”

“Please come to Lenox Hill Hospital right away. I am already there.”

I protest: “Why? Because it’s the heart? Is it really that urgent? I have never had a problem with my heart. With my head, yes; my stomach too. And sometimes with my eyes. But the heart has left me in peace.”

At that, he explodes: “This conversation makes no sense. I am your cardiologist, for heaven’s sake! Please don’t argue with me! You must take a number of tests that can only be administered at the hospital. Come as quickly as you can! And go to the emergency entrance!”

On occasion, I can be incredibly stupid and stubborn. And so I nevertheless steal two hours to go to my office. I have things to attend to. Appointments to cancel. Letters to sign. People to see―among others, a delegation of Iranian dissidents.

Strange, all this time I am not really worried, though by nature I am rather anxious and pessimistic. My heart does not beat faster. My breathing is normal. No pain. No premonitions. No warning. (5-6)

Passage #2:

Marion is still here, and in a flash I relive our life together, the exceptional moments that have marked it.

I recall our first meeting, at the home of French friends. Love at first sight. Perhaps. Surely on my part. I thought her not only beautiful but superbly intelligent. Hearing her discuss with great passion some Broadway play, I became convinced that I could listen to her for years and years―all my life―without ever interrupting her. I invited her to lunch at an Italian restaurant across from the United Nations. Neither of us touched the food.

Her background? Vienna, then fleeing from place to place; being imprisoned in various camps, including the infamous Camp de Gurs; eventually finding freedom in neutral miracles of adaptation, survival and extraordinary encounters. For years now I have been advising her―begging her, in fact―to write her memoirs. In vain.

We were married in Jerusalem by the late Saul Lieberman, in the Old City (then recently liberated), in the heart of an ancient synagogue, the Ramban, for the most part destroyed by the Jordanian army.

Since then, I cannot imagine my life, my lives, without her. (13-14)

Passage #3:

A great journalist, a friend, in a televised conversation, asked me what I would say to God as I stood before Him. I answered with one word: “Why?”

And God’s answer? If, in His kindness, as we say, He actually communicated His answer, I don’t recall it.

The Talmud tells me: Moses is present as Rabbi Akiba gives a lecture on the Bible. And Moses asks God, “Since this master is so erudite, why did You give the Law to me rather than to him?” And God answers harshly: “Be quiet. For such is my will!” Some time later, Moses is present at Rabbi Akiba’s terrible torture and death at the hands of Roman soldiers. And he cries out, “Lord, is this Your reward to one who lived his entire life celebrating Your Law?” And God repeats His answer with the same harshness: “Be quiet. For such is my will!”

What will His answer be now, to make me quiet?

And where shall I find the audacity and the strength to not accept it? (65-66)

Passage #4:

One day at the beginning of my convalescence, little Elijah, five years old, comes to pay me a visit. I hug him and tell him, “Every time I see you, my life becomes a gift.”

He observes me closely as I speak and then, with a serious mien, responds:

“Grandpa, you know that I love you, and I see you are in pain. Tell me: If I loved you more, would you be in less pain?”

I am convinced God at that moment is smiling as He contemplates His creation. (70)

Passage #5:

Have I performed my duty as a survivor? Have I transmitted all I was able to? Too much, perhaps? Were some of the mystics not punished for having penetrated the secret garden of forbidden knowledge?

To begin, I attempted to describe the time of darkness. Birkenau, Auschwitz, Buchenwald. A slight volume: Night. First in Yiddish, And The World Remained Silent, in which every sentence, every word, reflects an experience that defies all comprehension. Even had every single survivor consecrated a year of his life to testifying, the result would probably still have been unsatisfactory. I rarely reread myself, but when I do, I come away with a bitter taste in my mouth: I feel the words are not right and that I could have said it better. In my writings about the Event, did I commit a sin by saying too much, while fully knowing that no person who did not experience the proximity of death there can ever understand what we, the survivors, were subjected to from morning till night, under a silent sky?

I have written some fifty works―most dealing with topics far removed from the one I continue to consider essential: the victims’ memory. I believe that I have done all I could to prevent it from being cheapened or altogether stifled, but was it enough? And if I often published works―articles, novels―on other themes, I did so in order not to remain its prisoner. My battle against the trivialization and banalization of Auschwitz in film and on television resulted in my gaining not a few enemies. To my thinking, it was my duty to show that the sum of all the suffering and deaths is an integral part of the texts we revere. (40-41)

Please join us for next week’s tributes to Professor Wiesel at our Facebook!