Student rocketeers persevere and make history

By Patrick L. Kennedy

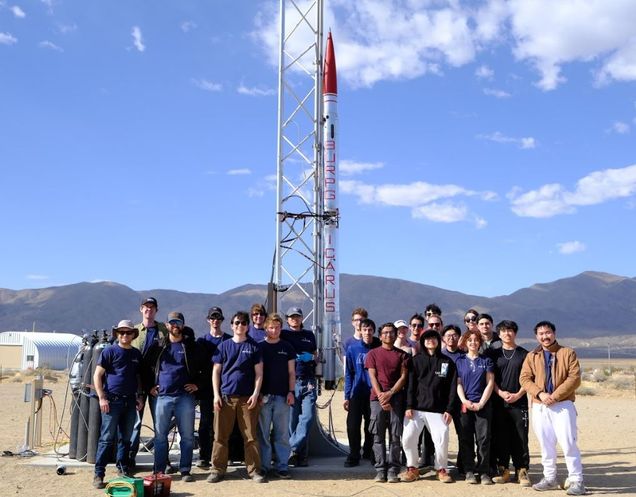

On March 29, the Boston University Rocket Propulsion Group (BURPG) launched and recovered Icarus, the first liquid-fueled rocket to be fired skyward by the student club in its 23-year history. The rocket also set a new record for the highest thrust of any collegiate liquid rocket to ever fly, with 2,200 pounds of sustained thrust. It was a momentous, early-career-defining achievement for all involved.

And it almost didn’t happen.

After they spent seemingly every spare moment for two years designing, building, and testing the 17-foot-long rocket, 19 of the students traveled to the Mojave Desert for the club’s first attempt at this feat, on March 1. They had to disassemble the rocket in Boston, ship it in two parts by freight to Los Angeles, fly themselves there, rent a truck and cars, collect the rocket parts, drive to the Friends of Amateur Rocketry launch site, and reassemble Icarus—this last step alone a day-long process.

After all that, they had to cancel the launch because of bad weather: gusts of wind approaching 60 miles an hour.

Twenty different hats

Those weren’t the only headwinds BURPG faced during its Icarus odyssey. Simply trying to operate a collegiate rocket team in the Northeast, the Terriers were at a disadvantage, relative to the many desert-proximate clubs on the West Coast. Nowhere in New England can you launch a rocket without it landing in a populated or wooded area, risking fires and casualties either way.

The students were, however, able to conduct stationary, ground-based fire tests at a secluded site in rural Massachusetts, albeit during the winter. To do this, they poured their own concrete slab and erected a steel testing structure, often working in rainy or near-freezing conditions.

“People put on 20 different hats,” says Ben Kamer (ENG’26), BURPG vice director. As one might expect, many of the club’s members are mechanical engineering majors, but there are also electrical and computer engineering majors as well as students from other BU schools, including majors in chemistry, computer science, and business.

“I worked on fluid systems design, but I learned so much about computers and electronics that I did not know, just because we’re talking to each other every day,” says Kamer. “This is the greatest team project. If you don’t communicate, it’s not like you get a bad grade—it’s that the rocket blows up, or it doesn’t come down in one piece.”

One of the hardest things

Icarus is a bipropellant rocket, powered by a mix of isopropyl alcohol and nitrous oxide. The students designed their own flight software and fluid systems from scratch, and they built hundreds of the rocket’s components themselves, machining parts in the BU Engineering Product Innovation Center and in the BURPG workshop on Cummington Mall.

When complete, the rocket measured 17 feet long and 8 to 9 inches in diameter. It weighed 190 pounds dry, or 250 pounds when filled with fuel. It consisted of two halves connected by an intertank housing the oxidizer and fuel fluid systems. The base was fitted with four fins for stability, and just above these a thrust structure assembly distributed loads from the engine to the rest of the rocket. At the other end, a compartment holding two parachutes, and an avionics bay containing a flight computer and GPS system were topped with a fiberglass-and-steel-tipped nose cone.

The windy weather that doomed the March 1 launch was just the latest of many setbacks, said BURPG director Kacper Bazan (ENG’25). “For the last two years, it was never smooth sailing. It was constantly annoying, tedious. This is technically, emotionally, logistically, one of the hardest things a lot of us have ever done.

“And yet,” added Bazan, when the students returned to Boston, “somehow the morale seemed so high, for everyone to go out again a month later without missing a beat, just to put all our marbles on the line to get it done.”

Alumni pitch in

In that effort to avoid missing a beat, the club got a huge assist from BURPG alum Jack Sullivan (ENG’23), now an electrical engineer at SpaceX in California. Sullivan had a storage space just big enough to fit Icarus without the nose cone, so the students didn’t need to disassemble the whole rocket after the aborted first launch, or reassemble it upon the return visit.

“That saved us a day and a half” of extra work, says Bazan.

Sullivan wasn’t the only alum who pitched in, notes Tim Evdokimov (CAS’25), BURPG treasurer: “The alumni support network was invaluable. Many came in or called in to our design reviews and provided feedback and technical advice. We could not have done this without the support of our amazing alumni who’ve gone on to industry and continued to provide all this invaluable insight into how to do all these very complicated things.”

Fifteen students made the return trip, camping out in tents in the desert. On launch day, after setting up Icarus on a 40-foot-high steel rail, the team members hunkered down at the controls in concrete bunkers 300 feet away. Students calmly announced the readiness of all systems, just as they’d rehearsed. Then, as the countdown clock clicked down to zero, they remotely set off the igniter.

Liftoff!

With first a whine and then a resounding roar, Icarus lifted off, and the shouting and cheering began. “We’d gotten quite good at keeping our cool during tests,” says Evdokimov. “During the launch, all that went out the window.”

“I felt an immense sense of awe,” says Bazan. “That, holy crap, we actually launched this thing.”

Burning through its fuel in 5.6 seconds and hitting a maximum velocity of Mach 1.6, Icarus reached an altitude of 12,900 feet in 30 seconds. Once the rocket hit its apex and began to fall, the parachutes deployed and the rocket “made its way leisurely down for the next minute and a half,” says Evdokimov, returning intact to Earth, to be recovered by BURPG.

Since starting at the club, many BURPG members have done internships and then landed jobs in the aerospace industry, following in the footsteps of Sullivan and many others.

As for the BURPG members who remain, and the new ones to come, the club retains a long-term goal of being the first collegiate team to fire a liquid-fueled rocket to the Karman line, 62 miles above sea level, touching outer space itself.

“You will succeed in doing the hard thing if you put enough effort into it,” says Bazan, reflecting on what he learned launching Icarus. “I will remember this experience my whole life.”

To learn more or support the work of BURPG, visit burpg.org.