Save the Date for the 9th Annual Center for Practical Theology Lecture!

You are warmly invited to

The Center for Practical Theology

9th Annual Lecture and Reception

Dean Bryan Stone will deliver the lecture on the topic of

“Evangelism, Religious Pluralism,

and the U.S. Military Chaplaincy”

Wednesday, October 12th, 2016

5:30 pm – 8:30 pm

Boston University School of Theology Community Center

(Lower level of School of Theology, located at 745 Comm. Ave, Boston, MA)

Reception begins at 5:30pm, with the lecture to follow.

Heavy hors d’oeuvres and drinks served.

Please email cpt@bu.edu with any questions.

We hope to see you there!

13th Annual Lecture for the Center for Practical Theology Announced

You are warmly invited to the Center for Practical Theology’s Thirteen Annual Lecture on Friday, December 4th, 2020 at 1pm on the zoom webinar platform. Dr. Heather Walton, Professor Theology and Creative Practice at the University of Glasgow School of Critical Studies, will present on “Body and Stone: Practical Theology as Creative Work.” Callid Keefe-Perry, Lecturer in Practical Theology at Boston University School of Theology, will offer a response following Dr. Walton's lecture. Please use this link to join the webinar. We hope to see you in December!

Creative Callings Innovation Hub Gathers Virtually

On October 3rd, the Creative Callings Innovation Hub gathered over zoom for their biannual meeting. Over 45 people, including lay and ordained leaders from twelve area congregations, BU STH faculty, and students from Dr. Wolfteich’s Vocation, Work, and Faith course, came together to reconnect and to reflect on the challenges and opportunities of discerning and embodying individual and communal vocation over the past 8 months. Through breakout discussions, activities, and worship, the gathering created space for sharing ideas, supporting each other, and asking hard questions.

Thank you to Dr. Claire Wolfteich, Dr. Teddy Hickman- Maynard, Dr. Jonathan Calvillo, Dr. Wanda Stahl, Dr. Courtney Goto, Jennifer Lewis, Cate Nelson, and Jamie Shore for making the event such a success!

The Creative Callings Project is funded by Lilly Endowment Inc. and fosters creative vocational discernment through an Innovation Hub of 12 Mainline Protestant congregation in the Boston area. Follow the link for more information about the Creative Callings Project: https://www.creativecallingsproject.org/project-details.

Welcome, New PhD Students!

As the School of Theology launches into a new school year, the Center for Practical Theology is delighted to welcome our new PhD in Practical Theology students. Please join us in congratulating Blair Stowe, Mary Wilson-Lyons, and Joshua Lazard as they embark on their studies this year!

Congratulations to Practical Theology Alum, Dr. Julian Gotobed!

Dr. Julian Gotobed (STH 03', STH 10') has been appointed as the Director of Practical Theology and Mission at the Westcott House in Cambridge, England. Congratulations!

Dr. Julian Gotobed (STH 03', STH 10') has been appointed as the Director of Practical Theology and Mission at the Westcott House in Cambridge, England. Congratulations!

Find more information about Dr. Gotobed's appointment and the Westcott House with the following link: https://www.westcott.cam.ac.uk/appointment-of-director-of-practical-theology-and-mission/

New Book by Visiting Researcher, Gail Cafferata, Featured on Faith & Leadership

“I didn’t know anyone else at that point who had closed a church, because no one in our diocese had done it,” she said. “And then I thought, ‘I wonder if anybody’s ever done a study?’”

This question, according to a recent article shared on Faith & Leadership (a resource for Christian leaders, from Leadership Education at Duke Divinity) prompted Gail Cafferata's newly released book, The Last Pastor: Faithfully Steering a Closing Church. Cafferata, a CPT visiting researcher, brought together her two decades of experience as a sociologist in higher education, with her personal experience as a pastor of a closing church, in order to research and reflect upon the phenomena surrounding the pastoring of closing churches.

The Center for Practical Theology congratulates Cafferata on the release of this book, as well as her feature on Faith & Leadership.

What Is The Point?: My Journey of Meaning Making in Practical Theology

By Farris Blount III, PhD Student in Practical Theology

Our world appears to be in steep decline. The global pandemic has laid bare the existing racial, social, and economic disparities in the United States, exacerbating the conditions in which millions were forced to live with prior to Covid-19. I live in Texas and have observed some troubling local realities as a result of this health crisis – possible evictions in the midst of rampant unemployment and reduced wages and increased exposure to food and “digital” deserts for children.

But what concerns me at a more fundamental, interpersonal level is what seems to be a pervasive lack of regard for human life. Despite data that demonstrates wearing masks can considerably reduce the spread of the virus, countless people have refused to do so. At the extreme, I have seen appalling videos of people coughing on others or engaging in behaviors that put people at risk. And lest we forget, we are also contending with another “pandemic” that has reared its head amid continuing police violence – the pandemic of racial injustice that has not valued Black lives since the beginning of America, often demonstrated through policies and practices that continue to emotionally, spiritually, psychologically, and literally kill African-Americans.

In times like these, I struggle to discern how to respond as a PhD student studying Practical Theology. I wonder, as I see friends advocating for police reform and budget changes or more equitable access to health-care in front of city councils or faith leaders preaching against the inequalities that permeate our culture, what my role in building the “beloved community” is as I spend the majority of my days reading and writing. If I am being honest, I have sometimes felt like I am not doing enough; it feels as if my work has no tangible impact on addressing the social ills of our time.

However, as I began to reflect more deeply on my discipline in this time of quarantine, I realized that it can offer hope and encouragement even in what appear to be hopeless times. In fact, Practical Theology has much to offer in how we must learn to live together as humans if we are to survive not only now but in the years to come.

Practical Theology, from definition to practice, is a collective endeavor. It is a field of study that attempts to describe what is happening in a given communal context in order to make claims about what should happen. It uses theological and sociological tools to understand human experience and chart a path forward in light of that experience. Practical Theology also, according to scholars such as Bonnie Miller-McLemore, is done by multiple persons; for example, believers within a faith community engage in practical theological work alongside pastors and clergy.[1] In Practical Theology, there are no gatekeepers to the work of making sense of our communities, no monopolies on who is allowed to voice their opinions on how our world should be transformed in light of our beliefs in and commitments to God and one another. In other words, Practical Theology’s focus on valuing all human life is inherent in its very DNA.

The discipline’s commitment to community, however, has a unique focus on drawing attention to those issues that prevent all human flourishing. Simply put, there is a branch of Practical Theology that can be considered liberationist. It is rooted in the belief that God is on the side of the oppressed, and Jesus came to liberate those who are on the margins of society.[2] Practical Theology uses this framework of Jesus as liberator to examine the unjust institutions that are causing harm. It applies a critical lens to discriminatory practices and policies in and outside of the church to critique but also to reimagine a world in which people, and Christians in particular, can be more faithful disciples to the call of Jesus to love our neighbors. It challenges us to consider that until all people are able to live free of fear of retaliation or violence, we have work to do.

In its commitment to liberation, Practical Theology makes the implicit statement that there is something wrong in how we often engage one another. When we value profits over people, mandating that businesses reopen in the midst of a pandemic without enough personal protective equipment to support those on the frontlines, something is wrong. When we demand that states rescind “stay-at-home” orders without adequately accounting for the disproportionate number of African-Americans that are suffering and dying from the coronavirus, something is wrong.

This particular understanding of Practical Theology has helped me process my role in this current pandemic and beyond. I do not have the exact response we each should have– speaking out against that which harms is exhausting, and people often have to self-reflect on their own level of commitment to establishing a more just society in the face of competing priorities. However, I do recognize that I have tools to examine critically why politicians are advocating for state re-openings despite the thousands of Black and Brown people who are at extreme risk of contracting a life-altering virus. I realize, through the foundational work of practical theologians such as Dale Andrews, there are supporting resources available as I work with colleagues to assess how our Christian commitments are either being weaponized to support a President whose actions are antithetical to the life of Jesus or utilized to imagine new ways for us to be in authentic and caring relationships with one another.

My journey as a practical theologian is far from over; in fact, it is just beginning. But I take solace in that I have embraced a discipline that provides a framework to question that which is in order to imagine what might be.

[1] Bonnie Miller-McLemore, ed., The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Practical Theology, (Indianapolis: Wiley Blackwell, 2014).

[2] Dale P. Andrews and Robert London Smith, Jr., Black Practical Theology (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2015).

Ministry in the Time of COVID-19: A Conversation with Nikki Young

Last Month, CPT Today Editor, Amy McLaughlin-Sheasby, reached out to Nikki Young to talk about the impact of COVID-19 on her work as a minister in Boston. Nikki just completed her second year in the Practical Theology PhD program at Boston University School of Theology, and also serves in ministry at Union Church.

-------

Amy: You are a PhD student in Practical Theology, but you are also a minister at a local congregation, so we are grateful for the opportunity to hear your unique perspective on ministry during this time of crisis. Could you begin by telling us about your church?

Amy: You are a PhD student in Practical Theology, but you are also a minister at a local congregation, so we are grateful for the opportunity to hear your unique perspective on ministry during this time of crisis. Could you begin by telling us about your church?

Nikki: Sure. Union is a vibrant faith community in the South End of Boston, that for over two-hundred years has remained committed to justice and liberation. Union is the first historically black United Methodist Church to become reconciling, which happened in the year 2000. The congregation itself emerged out of the struggles of slavery, and has developed and grown over time to be a really strong advocate, particularly in the South End, but also in the Greater Boston area as well. Union is a strong community of dedicated people, who worship in a building that now sits in a gentrified area of Boston, so we find ourselves in a place where our very DNA is multicultural, and incredibly diverse. So, while we stand in this African-American tradition of worship, we are now in a position where this history and tradition informs the way we think about intersectional justice. It’s really important to us, especially as United Methodists at this time. We are deeply committed to sharing stories, hearing stories, and developing new liberative narratives that actually serve as a witness, not only to our denomination, but the world.

Amy: When did you first get involved, and what is your current role?

Nikki: I first became involved at Union as a seminary student in my master’s program. Someone who is currently on the ministerial staff was in my orientation group at the School of Theology, and invited me to attend. So, I started worshiping for a year, did contextual education for the following year, and then was hired on staff shortly after. Now I serve as the Assistant Pastor at Union where I work with our lead pastor, Rev. Dr. Jay Williams, who is an elder in the United Methodist Church.

Amy: One of the reasons I reached out to you for this interview is because I follow your work closely as a friend and colleague, and I have seen you share on social media about how Union is adapting to COVID-19. How would you describe Union’s response to the pandemic, and how has the pandemic impacted your ministry?

Nikki: There’s a phrase that the saints used to say: “We’re gonna love everybody and we’re gonna treat everybody right.” I would say that has been our starting point for all of the ways in which we read scripture, do worship, engage in mission, etc. And I’m saying this particularly aware that the earliest phases of reopening Boston have involved reopening churches. I’m also aware that there have been faith leaders and colleagues here in Boston who have advocated for that to happen. At Union, we understand that people are vulnerable and that we have a responsibility to one another first and foremost, not just as Christians, but as human persons. So for us, it has been incredibly important to think about how we want to adapt in ways that keep people safe while also cultivating a spirit of worship in a new way.

Our plan, first and foremost, is to keep our people safe. We are not interested in returning to “business-as-usual” if it means putting those most vulnerable at risk. Instead, we have begun exploring even more ways to get folx the resources they need to stay healthy, safe, and connected. For us it’s an act of faithfulness to stay closed. We have, and will continue to meet for worship on Zoom for as long as we feel we need to.

Amy: What have you observed about your congregation over the last couple of months as you all have adapted your worship practices, and embraced virtual platforms?

Nikki: One thing that I have observed is the way this situation deeply illuminates that the church is far more than a building. I have also observed how congregants and leaders at Union, whose gifts have not regularly been put to use in church services in the past, are now stepping up and showing out in amazing ways. We have a great team, which includes some people who have been in leadership at Union for years and years, and some who have stepped up to leadership in the last month or two, who see the ways in which technology facilitates meaning-making, purpose, and belonging. This team is working day in and day out to develop elements of the service that are very much in line with Union’s mission and identity. I have also observed that we are learning to adapt wherever we need to adapt. Our songs are not as long. Our sermons sound and look different when we are sitting in front of cameras. But interestingly enough, all the adaptations have revealed new opportunities to lean into our mission. We have far more people attending our online services now than had been gathering in person. It has been teaching us that when we go back to normal life, we are not going to be able to be church the same way as before, because we have seen how doing church online is opening up access to our mission in ways that meeting in person has not.

Amy: It sounds like your core mission at Union has remained consistent, and has largely guided your reactions to the pandemic. But even as you maintain your core mission, has your ecclesiology or understanding of ministry changed or transformed in some way?

Nikki: I think this crisis has served as a catalyst for things that we had already been envisioning. We have had an opportunity over the last several weeks to move in the direction we felt like God was inviting us into. We are under an immense amount of pressure where creativity has to happen, and where we are released for a brief time from all of the mundane, every-day, business-as-usual things that usually take up our time. As a result, we have begun to develop an interconnected web of relationships that are helping to sustain people throughout the week. We are asking questions like, what does it mean to gather in worship? How do we make sure people don’t feel isolated? How do we make sure that not only spiritual needs, but also basic needs are being met? And how do we hold one another accountable? More than ever, this has helped to reaffirm the notion that we are beholden to one another, not only as an act of faithfulness, but as an act of justice, to create actual systems of connection between people.

Amy: Has there been a moment or a distinct interaction that made you think, even in the midst of everything going on, “Yes—this is who the church is called to be in this moment, for this community”?

Nikki: Yes. Two things come to mind. The first is a very practical, on-the-ground, missional aspect, which is that we have people working in our food pantry, still. Some of our members feel it is so important to be in this food pantry, that they continue to show up to do this work. Our volunteers are quite literally just out grinding every week, making sure people get fed. And this was never questioned, or up for debate. The only question they asked was simply, “Now that we are here, how can we adapt this ministry that we already have so that we are reaching the most amount of people?”

Nikki: Yes. Two things come to mind. The first is a very practical, on-the-ground, missional aspect, which is that we have people working in our food pantry, still. Some of our members feel it is so important to be in this food pantry, that they continue to show up to do this work. Our volunteers are quite literally just out grinding every week, making sure people get fed. And this was never questioned, or up for debate. The only question they asked was simply, “Now that we are here, how can we adapt this ministry that we already have so that we are reaching the most amount of people?”

I’m also reminded of Mother’s Day Sunday, which landed on the Sunday just after Ahmaud Arbery’s video came out. It was in the news, there were hashtags, and for our community in particular, it hits not just close to home, but in the body. It became deeply important to tap into our traditions, to look to womanist theology, to listen to music that came from the saints before us, to communally lament on a day when we typically celebrate mothers. All of these activities became important sources of meaning-making, lamenting, and hope-building in the midst of absolute destruction. During the Mother’s Day service, you could see people weeping in their video windows on Zoom. I think it really touched people.

It occurs to me that there is a myth circulating out in the world that church online is somehow less church—like it’s the faux church that we have to do until we can get back to doing real church. But at the end of the day, it is still real human persons connecting to one another. We have to build hope, even as we are socially isolated.

Amy: When we originally scheduled this interview, I had expected to primarily address the impact of COVID-19, but now our nation has catapulted into some important acts of consciousness-raising concerning racism, white supremacy, and police brutality. Given Union’s longstanding dedication to justice in Boston and the broader world, would you like to speak to the present moment? How are you thinking about Union’s dedication to justice, even as we continue to endure this pandemic?![]()

Nikki: On Pentecost Sunday, the Feast of Breath, we opened with a litany of lament. The gospel we proclaim is inextricably bound to a brown, Palestinian-born man who was terrorized and killed by the State. That the world watched as he breathed his last, that some shrugged at this while others wept, and that this Divine made flesh was not so easily loved by the world—we understand this because so many live it. I think, especially as a white pastor situated in a church like Union, the work is not just in condemning police brutality and white supremacy, it is in uprooting the long-lasting Christian theological strongholds that have always been inextricably bound to oppression. Because the Church cannot breathe with the weight of white supremacy on its neck.

Amy: Amen. May you all continue to find ways to live out your mission in this present moment. Thank you for taking the time to share with us at CPT Today.

CPT Co-Director, Courtney Goto, wins BU Metcalf Award for Excellence in Teaching

Congratulations Dr. Courtney Goto!

Congratulations Dr. Courtney Goto!

The Metcalf Cup and Prize is the highest teaching honor at Boston University. Dr. Goto was nominated by students and vetted by a University team in an extensive process. We are so happy to celebrate alongside Dr. Goto and the rest of the BU STH community.

Read more about the Metcalf Award and ceremony, here.

Read Dr. Goto's profile in BU Today, here.

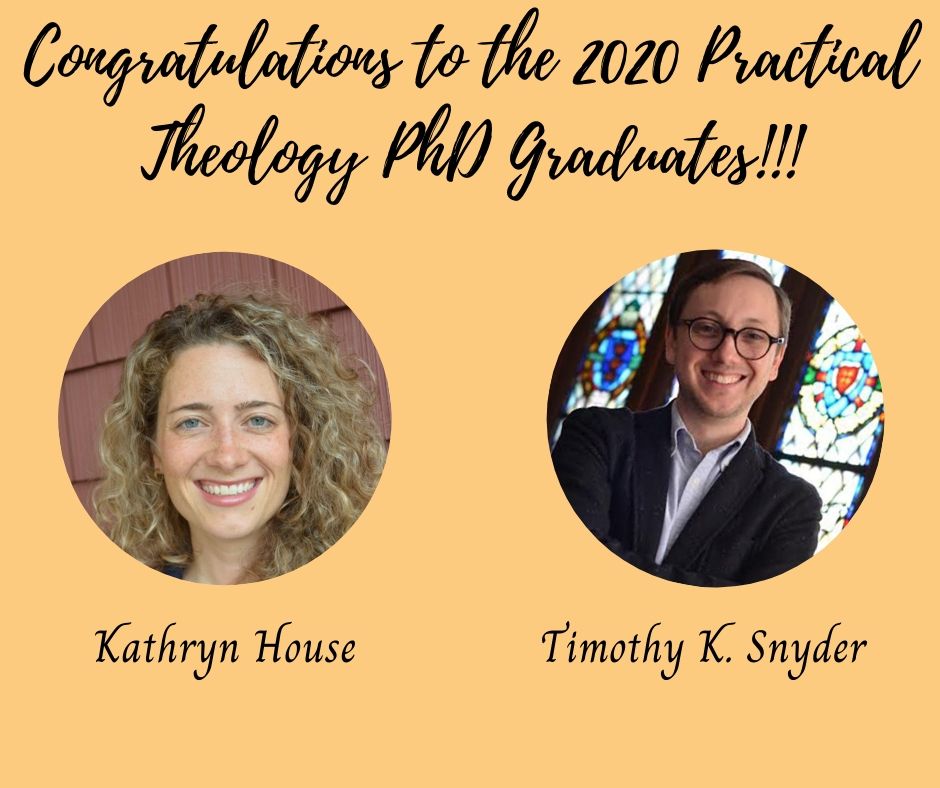

Congratulations, 2020 Practical Theology Graduates!

Congratulations to the 2020 Practical Theology PhD graduates!

Dr. Kathryn House: The Afterlife of Evangelical Purity Culture: Wounds, Legacies, and Impact

Dr. Timothy Snyder: Modern Work and Meaning: Towards a Lived Theology of Work

Book Review: Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, edited by Craig Detweiler

Dominic J.S. Mejia, MDiv Candidate at the BU School of Theology, recently reviewed Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, edited by Craig Detweiler. Find the full review below.

Dominic J.S. Mejia, MDiv Candidate at the BU School of Theology, recently reviewed Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, edited by Craig Detweiler. Find the full review below.

Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, edited by Craig Detweiler. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010. 248 pages. $25.00.

Faith and Video Games: A Brief Survey and Response

Summary

Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God edited by Craig Detweiler[1] – This volume, written in 2010, is a compilation of standalone essays that seeks to introduce theology as a methodology by which video games might be assessed.[2] The first of three parts offers different approaches to studying video games through the lenses of storytelling (narratology) and/or game design (ludology).[3] The second section is composed of interviews with game designers and reflections by players regarding their experiences of video games. The third section offers meditations on personhood, community, and imagination in light of the digital worlds that gamers inhabit. Detwiler concludes the volume with the corniest chapter I have ever read. All but one of the chapters focus on Christian theologies of video games, with the exception being a fascinating look at “Islamogaming,” which explores the ways Muslims use a medium that often objectifies them to subvert expectations and offer alternative messaging.[4]

Of Games & God: A Christian Exploration of Video Games by Kevin Schut[5]– Kevin Schut opens his book stating that he is seeking to help Christian communities develop “a balanced approach to computer and video games.”[6] He sticks to this commitment throughout his book, weighing the dangers of gaming (the glorification of violence, the potential for addiction)[7] with the gifts gaming offers (alternative realities to be explored, tools for education, foundations for community).[8] Ultimately, he argues for robust Christian criticism that pays attention to the context of a game, draws on different critical perspectives, uses scripture and Christian traditions as a means of evaluation, and does not view games as essentially good or bad.[9] Throughout, Schut remains committed to an evangelical understanding of the Christian faith, seeking to discern how video games, and the community around them, might serve as foundations or media for evangelism.[10] At the same time, he decries Christian cultural insulation, whereby Christians produce material for Christians to avoid engaging with outside cultural materials.[11]

God in the Machine: Video Games as Spiritual Pursuit by Liel Leibovitz[12] – The subtitle of this book is a misnomer. Rather than seeking to show how playing video games might be a spiritual practice, Leibovitz instead suggests that video games are more like spiritual practices than they are like other forms of media.[13] He writes, “Religion, then, is exacting but modular, rule-based but tolerant of deviation, moved by metaphysical yearnings but governed by intricate, earthly designs. Religion is a game.”[14] He attempts to make his argument first by looking at how game design sets the parameters for engagement, then by describing what embodied persons do when they play video games, then by exploring the nature of “cheating” in single-player videogames, before ending with the fairly bold claim that video games are the ideal means by which people might experience timelessness, and are thus similar to religious experiences.

Analysis

Halos and Avatars – The essays found in this volume highlight several different loci to take into account when constructing theological considerations of video games. Throughout the book, authors take different approaches, either privileging the narrative of a game (narratology) or the design of a game (ludology) as their primary grounds for interpretation. For example, “Wii are Inspirited,” looks at what the Nintendo Wii console, by its design, says about humanity’s embodied nature; whereas “From Tekken to Kill Bill: The Future of Narrative Storytelling” focuses on how the narrative style of video games, namely, the structure of video game levels, might influence filmmaking.[15] If one takes a narratological methodology for interpreting a game, especially for the sake of doing theology, one is likely to be disappointed. As Chris Hansen writes, “Perhaps the surface pleasures of gaming can only reduce the complexities of film.”[16] Video games are not primarily a narrative medium, though narrative plays a crucial role. The essays that take a ludological approach tend to raise many more interesting questions. For example, Jason Shim explores the intricacies of a virtual wedding afforded by the design of the game Second Life, and the questions of identity and embodiment raised by these phenomena.[17] Video games are not films, just as films are not novels. To treat them as such is to fail to recognize the unique manner in which Gospel might emerge in the medium.

Of Games & God – Schut’s primary project begins with the Christian person. What does it mean for a Christian to play and make video games? In this regard, Schut’s work is consistently concerned with ethics. This work begins by considering the many facets of video games. He argues that video games communicate through signs (visual, aural, spoken), narrative, and game design, are filled with interactive and systematic information, and mean nothing without a player.[18] Schut places the onus for responsible engagement with video games on the player. In a chapter based on interviews with several Christian video game developers, Schut speaks a warning against reducing the church to a marketing demographic.[19] While all video games are not created equal, and the narrative or design of some games, particularly when it comes to violence, addictive design, or over-sexualization of women, should be cautioned against, Schut suggests that it is the faithful who bring faith into a game through how they interact with the medium. In this regard, for Schut, the way for a Christian to critically engage with a game is to look at that which emerges in the dialogue between the game and the player.

God in the Machine – Leibovitz takes video games deadly seriously. He writes, “What’s truly frightening about the question is that playing video games—like kneeling in prayer or making love or running a race or listening to music or any other heavily sensual and deeply emotional undertaking—is an experience that does not readily lend itself to description.”[20] Similar to Schut, Leibovitz finds the meaning of video games in the experience of the player – although he is interested more in what the player experiences in the state of play, whereas Schut was concerned with what it means for Christians to play video games. Leibovitz states that video games are code, not art, which limits the possibilities found in video games.[21] As such, it is the experience of playing video games which is crucial to understand them, as video games in and of themselves cannot “mean” anything more than they are programmed to. Unlike Schut, however, Leibovitz is not concerned with the external goods of games, such as discerning meaning or finding community through playing. Rather, the value of video games is that they are a means of wasting time in a modern context that emphasizes productivity over all else.[22] In this regard, playing video games might be similar to religious practice, in that spiritual disciplines are not necessarily concerned with a result, but are valuable in and of themselves – as playing video games (when not done professionally) does not produce much.

Evaluation

Halos and Avatars – It is with confidence, having now completed my course work for my Master of Divinity degree, that I can say Craig Detwiler offers the most cringeworthy paragraph regarding theology and pop culture that I have ever read. He writes,

Jesus dropped into the game of our world with both remarkable (even divine) skills and crippling limitations (of humanity). He explored many corners of his Middle Eastern ‘island.’ Among his contemporaries, he made both friends and enemies. A tightly knit, dedicated community arose around him. Jesus and his clan experienced plenty of grief from aggressive and uncooperative rivals. He was eventually fragged during a deathmatch on an unexpected field of battle. He submitted to the rules of engagement, even while resisting them, proposing an alternative way to play. After three days, Jesus respawned, took his place as Administrator, and redefined the way the game is played.[23]

Detwiler’s quote represents the worst of the volume. It is a cheap one-to-one mapping of a Christian message over video games through an arbitrary and inappropriate cooption of gamer lingo. It is simultaneously insulting to people who play video games and crassly trivializing of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. Not to mention ableist or generally misanthropic, depending how one takes “crippling limitations (of humanity).” The worst essays in the volume fail to understand that video games are fundamentally different from other forms of expression, as Detwiler fails to engage theology with video games and vice versa.[24]

At its best, Halos and Avatars offers thoughtful reflections on different aspects of and potential in games. Mark Hayse explores how Ultima IV allows the player to explore and discover a world where the moral rules are unclear yet impact each aspect of gameplay, offering an interesting playground for reflecting upon real-world ethical systems.[25] Kevin Newgren combines narratology and ludology to show how BioShock, through gameplay fixed within a robust narrative, might challenge both Randian objectivism and raise questions about the extent to which the protagonist, and therefore the gamer, can act with free will.[26] Rachel Wagner explores different games that represent Christ to show how games do not lend themselves to fixed narratives and therefore can be offensive when portraying sacred stories.[27] It is theologically complicated to actively interact with and potentially change sacred narratives. These robust essays engage the medium in general, as well as particular games, with thoughtfulness and consideration of what makes games unique; exploring the pitfalls of video game interactivity, showing how narrative and game design are interwoven in the most theologically generative games, and highlighting that interactivity and exploration are the fundamental frames through which theological consideration of games might take place.

Of Games and God – Schut succeeds in his task of offering a balanced approach to video games from an evangelical Christian perspective. His most interesting work is in his careful attending to how Christianity specifically, and religion and general, can be cheapened and mechanized through the creation and marketing of interactive media. While responding to concerns that video games promote the demonic and anti-Christian, Schut sneaks in a critique that video games often reduce religion to a character statistic, a faction, or a power, thus making faith a means to an end, as opposed to a way of life valuable in and of itself.[28] This is not restricted to non-Christian games, as the author highlights how the game Left Behind: Eternal Forces makes use of a “spirit level” which determines if a character is in the “Christian Tribulation Forces” or in the antichrist “Global Community.”[29] There are many theological issues with that particular game that they barely warrant mention.[30] To get the ball rolling, Left Behind reduces evangelism to a function, tacitly encourages Christians to kill their enemies, and reduces God to some kind of magical ally that helps in human war; all of which reflect a narrow and harmful eschatological understanding

Fundamentally, Schut successfully troubles the categories of “Christian” and “non-Christian” in video games. So-called Christian games can be reductive and insulting to the Christian faith; so-called secular games can be deeply theologically generative for Christians. More than striking a balance, Schut offers different criteria of evaluation more meaningful than the marketing and symbology of a particular game.[31] Video games offer opportunities for players to encounter God in new venues, explore their ethics and how they play out in a digital world, and connect with other players. The content of the game must be weighed against the value of these characteristics, and how the act of play engages these characteristics, in any title. Instead of asking if a game is marketed to Christians, one should ask if a game is theologically and faithfully generative when engaged with by Christians.

God in the Machine – Ultimately, Leibovitz’s book is not worth the read. He cites figures such as Maimonides, Descartes, Hegel, Augustine, Aristotle, and others from the pantheon of great (male) Western philosophers to say little more than video games are made of code, wasting time is okay in a modern context, people’s bodies respond to video games, cheating in single-player games is okay because the developers put the cheats in, players feel empathy for the characters they control, video games have stories with characters, and video games are composed of a series of events; all of which could have been stated in an article, or simply didn’t need to be said. He hides the pointlessness of his work behind technical philosophical jargon and overdramatization of the “work” of playing videogames.[32]

This emptiness is revealed through his assumption that all religious practices are the same (they’re not) and by a methodology for assessing video games that was based on his taste in video games, and not in through a broader study of different forms of games. His favorite games tended to be linear, single-player adventure games and arcade games, thus limiting the scope of what he could say about games in general. I agree with Robert Geraci, who writes of this text, “Ultimately, the book ignores scholarly work on games and on religion, investigates only a very few games, offers little empirical evidence, and never defines key issues, such as ‘spiritual pursuit’ or the religious ramifications of gaming.”[33] I hoped God in the Machine would eventually make a point more profound than what can be gleaned by my playing of games on a Friday night. Instead, I found a text that is simultaneously too jargon-y to be approachable and too theoretically milquetoast to be meaningful.

Response/Synthesis

As revealed through all three texts, either by their success or their failure to engage theologically with video games, the foundation for the assessment of video games is found in the playing of them. Sports games such as Madden NFL play entirely different than first-person shooters such as Call of Duty: Modern Warfare or open-ended adventure games such as Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. More than simply being different genres of games, swapping one set of aesthetic principles for another, different games have different goals and means of engaging that demand different postures of reflection. Perhaps the locus for theological engagement in Call of Duty will be related to the ethics of Christians killing digital figures, whereas Legend of Zelda might prompt exploration of the in-game religion that emerges as the player encounters the world. The reason for playing – either to score the most points, or to defeat an international terrorist organization, or to be the last surviving player, or to triumph over ancient evil – shifts the meaning of the act of playing.

This said, I propose three theological loci for engaging with video games, gleaned from the texts that I read for this project. The first is theological anthropology. This foundation asks the question, “what does it mean that we play like this?” This form of inquiry is found in Kallaway’s essay on embodied play through the Nintendo Wii, which he uses to speak against disembodied Neoplatonism in the Christian tradition.[34] This is also highlighted in Schut’s and Leibovitz’s work, who highlight the importance of the embodied experiences of the player as they engage with a game. Detwiler, Leibovitz, and Schut all draw on the work of Dutch sociologist Johan Huizinga to suggest that people, on some basic level, are created to play.[35] A theological anthropological approach to video games seeks an inductive understanding of what it says about people, and therefore God, the Creator, Sustainer, and Redeemer of creation, that we are inclined to play. I’m reminded of Psalm 104:24-26, which suggests God desires for creation to play. [36] Furthermore, if one agrees with Barth that human nature is perfected in Christ, and agrees that it is human nature to play, one could argue that play is an aspect of the Incarnate God’s nature as well.[37] From there, one might begin to explore what it means for this person, to play this game, in this way.

The next theological locus is the ethical/imaginative. In preparing for this project, I read Hauerwas’s writing on the ethics of pacifists reading murder mysteries.[38] While arguing why the particulars of murder mysteries make the genre helpful for Christians to read, Hauerwas offers a few theoretical points that might apply to video games: first, that “popular” media can serve as a crucial means of speaking to the “eternal yearnings of the human condition”; and, second, that even violent media might speak to the Christian belief that evil is bounded by good.[39] The imagination is shaped, but the violence isn’t “real.” This resonates with Schut’s careful consideration of finding a balanced approach to video games, as well as several articles in Halos and Avatars that discuss how video games allow people to play with the ethical ramifications of decisions in a context that does no real harm. The player is encouraged, in other words, to explore their ethics in a game world. As Daniel White Hodge writes, “By engaging in narrative, gamers are able to experience God in an entire new dimension and are allowed to find God on their own terms within that story – not within the confines of a prepackaged salvation formula.”[40] Might some games lead to misshapen ethical imaginations? Yes. That is why careful critical assessment is necessary. But no genre of video game should be dismissed without consideration.

A final theological consideration is to name the possibility that God might be encountered within a digital landscape. To paraphrase John 3:8, the Spirit blows where she will. Video games might be a means of grace. In times of social isolation, video games are a reprieve from our one-bedroom apartments and offer worlds to explore.[41] For some who are grieving, video games provide a way to externalize and process the pain, as well as serve as tools for the training of caregivers.[42] For others, some games are simply so beautifully constructed, so joyful, so narratively compelling, that the player might experience a moment of transcendence. Truth, goodness, and beauty are encountered differently when the subject can interact and engage with the components that manifest them. Sure, they’re games. But games matter.

Bibliography

Auxier, John W. “That Dragon, Cancer Goes to Seminary: Using a Serious Video Game in Pastoral Training.” Christian Education Journal 15, no. 1 (2018).

Barth, Karl. “Barth: Christ and Adam.” In Readings in Christian Theology, edited by Peter Crafts Hodgson and Robert Harlen King, 157–61. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985.

Callaway, Kutter. “Wii Are Inspirited: The Transformation of Home Video Consoles (and Us).” In Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, edited by Craig Detweiler, 75–90. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010.

Campbell, Heidi. “Islamogaming: Digital Dignity via Alternative Storytelling.” In Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, edited by Craig Detweiler, 63–74. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010.

Detweiler, Craig, ed. Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010.

Geraci, Robert M. “God in the Machine: Video Games as Spiritual Pursuit. By Liel Leibovitz. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton, 2013. Pp. Xii +144. Cloth $19.95; Paper, $10.47.” Religious Studies Review 42, no. 2 (2016): 100–101.

Hansen, Chris. “From Tekken to Kill Bill: The Future of Narrativve Storytelling” Focuses on How the Narrative Style of Video Games Migh Influence Filmmaking.” In Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, edited by Craig Detweiler, 149–62. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010.

Hauerwas, Stanley. “McInerny Did It: Or, Should a Pacifist Read Murder Mysteries?” In A Better Hope: Resources for a Church Confronting Capitalism. Democracy. And Postmodernity, 201–10. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Brazos Press, 2001.

Hayse, Mark. “Ultima IV: Simulating the Religious Quest.” In Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, edited by Craig Detweiler, 34–46. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010.

Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Humanitas, Beacon Reprints in Humanities. Boston: Beacon Press, 1955.

Leibovitz, Liel. God in the Machine: Video Games as Spiritual Pursuit. West Conshohocken, Pa.: Templeton Press, 2014.

McAlpine, Andrew. “Poets, Posers, and Guitar Heroes.” In Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, edited by Craig Detweiler, 121–34. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010.

Newgren, Kevin. “BioShock to the System.” In Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, edited by Craig Detweiler, 135–45. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010.

Schut, Kevin. Of Games and God. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Brazos Press, 2013.

Shim, Jason. “’Til Disconnection Do We Part: The Initation and Wedding Rite in Second Life.” In Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, edited by Craig Detweiler, 19–33. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010.

Suderman, Peter. “Opinion | It’s a Perfect Time to Play Video Games. And You Shouldn’t Feel Bad About It.” The New York Times, March 23, 2020, sec. Opinion. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/23/opinion/video-games-covid-distancing.html.

Wagner, Rachel. “The Play Is the Thing.” In Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, edited by Craig Detweiler, 47–62. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010.

White Hodge, Daniel. “Role Playing: Toward a Theology of Gamers.” In Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, edited by Craig Detweiler, 163–75. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010.

[1] Craig Detweiler, ed., Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010).

[2] Ibid., 9

[3] Ibid., 20-22.

[4] Heidi Campbell, “Islamogaming: Digital Dignity via Alternative Storytelling,” in Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, ed. Craig Detweiler (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 63–74.

[5] Kevin Schut, Of Games and God. (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Brazos Press, 2013).

[6] Schut., 2.

[7] Ibid., 51-108.

[8] Ibid., 29-50, 109-170.

[9] Ibid., 176-177.

[10] Ibid., 127-169.

[11] Ibid., 168.

[12] Liel Leibovitz, God in the Machine: Video Games as Spiritual Pursuit. (West Conshohocken, Pa. : Templeton Press, 2014).

[13] Ibid., Kindle location 62-63

[14] Leibovitz., location 75.

[15] Chris Hansen, “From Tekken to Kill Bill: The Future of Narrativve Storytelling” Focuses on How the Narrative Style of Video Games Migh Influence Filmmaking,” in Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, ed. Craig Detweiler (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 19–33; Kutter Callaway, “Wii Are Inspirited: The Transformation of Home Video Consoles (and Us),” in Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, ed. Craig Detweiler (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 75–90.

[16] Hansen, 28.

[17] Jason Shim, “’Til Disconnection Do We Part: The Initation and Wedding Rite in Second Life,” in Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, ed. Craig Detweiler (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 149–62.

[18] Schut, 27-28.

[19] Ibid., 140-141.

[20] Leibovitz, Location 533.

[21] Ibid., Location 133.

[22] Ibid., Location 453.

[23] Detwiler, 196.

[24] Examples: Hansen, “From Tekken to Kill Bill: The Future of Narrative Storytelling." Hansen decries the influence of video games on film, nameley, the Tekken series on Kill Bill, by arguing that video games are not narratively robust; Andrew McAlpine, “Poets, Posers, and Guitar Heroes,” in Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, ed. Craig Detweiler (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 121–34. McAlpine argues that Guitar Hero is bad because people aren’t making real music. Both misunderstand the nature of video games.

[25] Mark Hayse, “Ultima IV: Simulating the Religious Quest,” in Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, ed. Craig Detweiler (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 34–46.

[26] Kevin Newgren, “BioShock to the System,” in Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, ed. Craig Detweiler (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 135–45.

[27] Rachel Wagner, “The Play Is the Thing,” in Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, ed. Craig Detweiler (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 47–62. This in itself raises interesting theological questions. Would the life, death, and resurrection of Christ remain salvific if things played out differently? I would argue that the Gospel would have still made salvation.

[28] Schut, 34-40.

[29] Ibid., 39-40.

[30] To start, the reduction of evangelism to a function, the problematic nature of having Christians kill their enemies, as well as a particular, narrow eschatological understanding.

[31] See Schut, 140-141.

[32] An example: “The game did me violence: it forced me to bend my hands and twist my fingers and strain my wrist in an effort to achieve the correct grip on the controller, and it subjected me to a stream of perpetual virtual battles, each causing me to tense my shoulders, arch my back, and furiously flick my thumbs. But the longer this violence occurred, the more ready I was to reenter the world of the game—this time, however, armed with new ways of being.” Leibovitz, 1121-1125.

[33] Robert M. Geraci, “God in the Machine: Video Games as Spiritual Pursuit. By Liel Leibovitz,” Religious Studies Review 42, no. 2 (2016): 100–101.

[34] Callaway, “Wii Are Inspirited: The Transformation of Home Video Consoles (and Us).”

[35] Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture, (Boston: Beacon Press, 1955).

[36] “O Lord, how manifold are your works! In wisdom you have made them all; the earth is full of your creatures. Yonder is the sea, great and wide, creeping things innumerable are there, living things both small and great. There go the ships, and Leviathan that you formed to play in it.”

[37] Karl Barth, “Barth: Christ and Adam,” in Readings in Christian Theology, ed. Peter Crafts Hodgson and Robert Harlen King (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985), 157–61.

[38] Stanley Hauerwas, “McInerny Did It: Or, Should a Pacifist Read Murder Mysteries?,” in A Better Hope: Resources for a Church Confronting Capitalism. Democracy. And Postmodernity (Grand Rapids, Mi.: Brazos Pres, 2001), 201–10.

[39] Ibid., 202 and 207, respectively.

[40] Daniel White Hodge, “Role Playing: Toward a Theology of Gamers,” in Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, ed. Craig Detweiler (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 165.

[41] Peter Suderman, “Opinion | It’s a Perfect Time to Play Video Games. And You Shouldn’t Feel Bad About It.,” The New York Times, March 23, 2020, sec. Opinion, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/23/opinion/video-games-covid-distancing.html.

[42] John W. Auxier, “That Dragon, Cancer Goes to Seminary: Using a Serious Video Game in Pastoral Training ,” Christian Education Journal 15, no. 1 (2018).