Save the Date for the 9th Annual Center for Practical Theology Lecture!

You are warmly invited to

The Center for Practical Theology

9th Annual Lecture and Reception

Dean Bryan Stone will deliver the lecture on the topic of

“Evangelism, Religious Pluralism,

and the U.S. Military Chaplaincy”

Wednesday, October 12th, 2016

5:30 pm – 8:30 pm

Boston University School of Theology Community Center

(Lower level of School of Theology, located at 745 Comm. Ave, Boston, MA)

Reception begins at 5:30pm, with the lecture to follow.

Heavy hors d’oeuvres and drinks served.

Please email cpt@bu.edu with any questions.

We hope to see you there!

Save the Date – Annual Lecture 2022

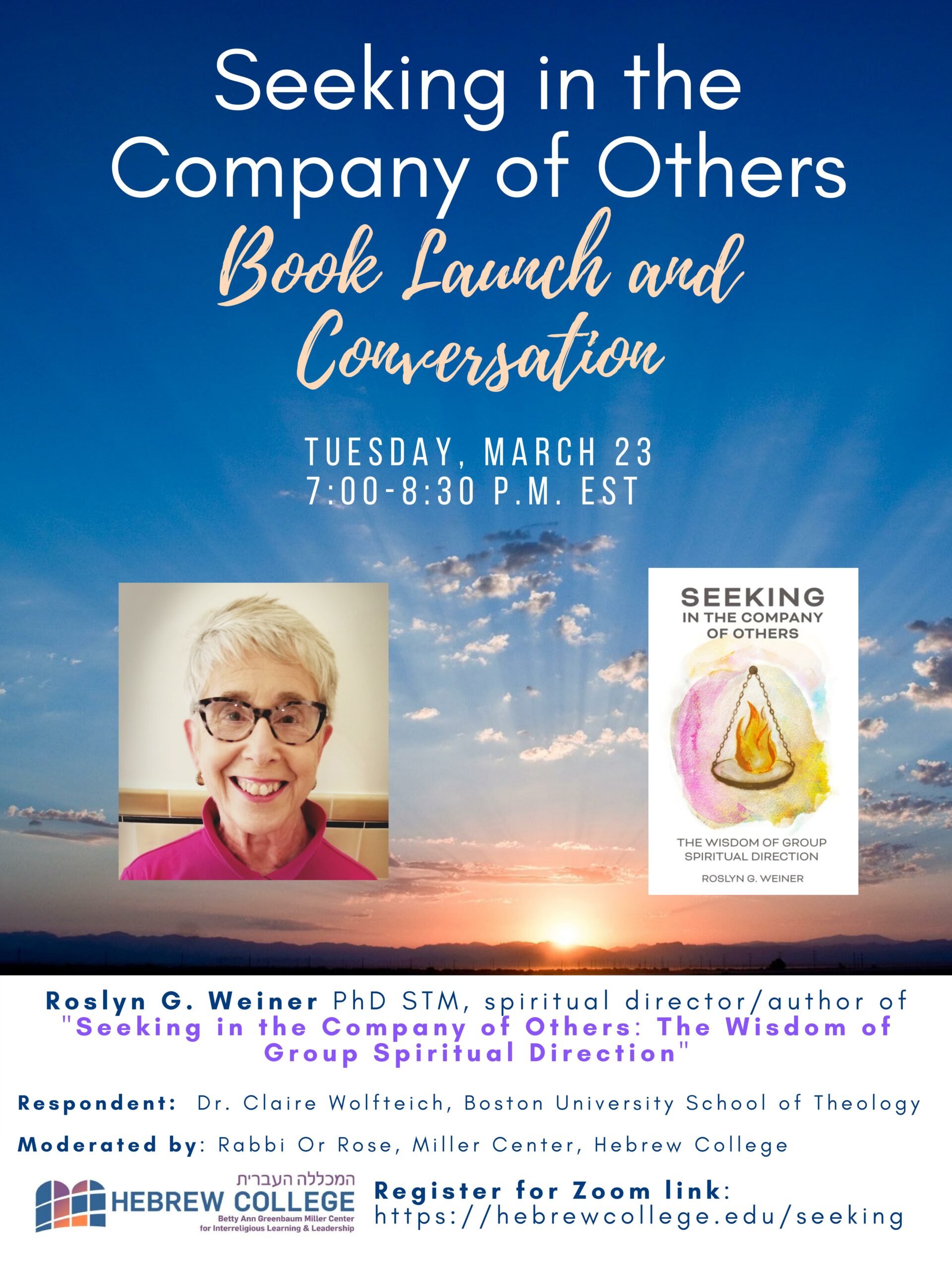

Seeking in the Company of Others: Book Launch and Conversation

14th Annual Lecture: What Does it Mean to be a Practical Theologian?

The Center for Practical Theology at Boston University held its 14th Annual Lecture on the evening of November 9, 2021. For this year’s event, we decided to explore the diverse vocational trajectories of some of our Practical Theology Ph.D. graduates and to create an interactive space in which current students, program alums, and faculty could reflect together on the field.

Our panelists included the Rev.Drs. Timothy Adkins-Jones, Diana Ventura, Mother Susan Forshey, and Montague Williams. Each of them spoke for ten minutes on the following questions:

- What does it mean to be a practical theologian?

- How does your own particular journey as a practical theologian surface insights and questions that we might name and reflect upon together?

The panelists were warmly received by the forty people who attended the lecture via Zoom. Various students, faculty, and alumni were moved by their insights and brought even more questions to the table. There was such a desire for continued conversation that the event went on longer than expected.

If you missed it, or wish to revisit it, you can watch a recorded version on Facebook.

Trauma Response Program for Congregations: A Conversation with Shelly Rambo

For this article, Dr. Shelly Rambo joined CPT Today Editor, Amy McLaughlin-Sheasby for a conversation about the new grant-funded Trauma Response Program for Congregations. For congregational leaders who are interested in applying to participate in this program, please find application information at the bottom of this article, or visit the program website: https://www.traumaresponsivecongregations.org/

Amy: We introduced the Trauma Response Program for Congregations earlier this summer when we released our annual CPT Newsletter, but for those who are not familiar, could you describe the project?

Shelly: Well, it is still evolving. I've been working on this other grant, thinking about chaplaincy education, and it became clear that the skill set of chaplains—the crisis care, immediate care, the work and pace—this skill set is going to be required of all congregational leaders. Congregational care and chaplaincy care are often separated, due to different settings and vocational tracks of faith leaders. But I became aware that a lot of the wisdom and skills that chaplains were engaging on a daily basis could be helpful to congregational leaders. Congregations are facing trauma, but they often have very little training on how to engage trauma. So, my hope was to offer the best of the research that we are doing at Boston University. We have certain “sweet spots” in congregational studies and trauma studies, and commitments to thinking about the impact of trauma on Black and brown communities. How do you weave justice and care into thinking about how congregations can thrive? It made sense to bring some of the research that we were already doing at BU, and things that are just so central to who we are, to thinking about how we can support congregations.

Lily Endowment launched a new initiative to explore what enables congregations to thrive. The language of thriving is often associated with resilience in trauma research circles. What are the ingredients to thriving? It was obvious to me that thriving is possible, only if trauma is attended to or responded to. So that is how I would describe the birth of the grant.

Amy: How will the project take shape? What is your plan?

Shelly: Our focus is on three cities. We wanted to think specifically about urban congregations, and to learn more about what congregations are already doing. So, one of the distinctive things about the grant, I think, is that we are not putting forward a trauma-informed model that we want participating congregations to implement. Instead, it is much more inductive—a form of accompaniment—to say we’re interested in how congregations in San Diego, Atlanta, and Boston are already responding to trauma. We are not assuming that they're not responding; they just may not use the language of trauma to describe what they are doing. There is so much information about trauma available. But the challenge is that it does not readily translate into the home language of most congregations—the language of faith. We can help with that, since many of us on the leadership team have been moving between the therapeutic and theological worlds with careful attention to how trauma can be addressed from within faith communities. We do know there is need. COVID added to the already existing stressors. So, urban congregations are already responding to a lot. Our question was, can we accompany them? Can we provide support through mutual learning and mentoring?

Amy: Does that support include financial assistance for the program?

Shelly: Yes. An important piece of the grant is to provide them some funding to do something very congregationally specific. So, they'll have a cohort of other congregations who are reflecting and thinking about what they're facing. There'll be some learning modules and then there will be a pilot project phase, which will be very specific to their congregation.

Amy: When project coordinator, Dayna Olson-Getty wrote for our CPT Today newsletter, she mentioned how the project aims to promote mutuality between educators and congregational leaders. I'm curious to know, even in these early stages of the project, what you are discovering in your interactions with congregational leaders?

Shelly: We're launching a call for proposals in August. We are asking congregations to participate in this program in which there will be an aspect of learning together. There will be some informational pieces from leading people in the field of trauma and moral injury—some of that will be asynchronous, made possible by all the technology that we now have. There will be a learning process together, which will largely take place in the fall. We hope congregations will apply. Applications are due September 30. Those who are accepted will join two other congregations in their city, nine in total. So, even though the project has not officially started yet, we have developed a model for this project that is very collaborative, which is super exciting already.

We have selected an advisory team of educators and leaders from the different cities. We've chosen people who are spiritual care educators, theological educators who are attentive to issues of trauma, trauma-response, and trauma care. So, the work of this summer has been to compile this really amazing team. We were initially calling them educators because we thought, “Oh, this is our educational team that’s going to help the congregations,” but we're really interested in mutuality, and the various kinds of conversations hat can emerge in such a model. Often, the danger in grants is that we have a research project we are going to carry out with certain desired outcomes, and assumptions. We have some learning opportunities that we want to gather these congregations around, but we don’t know how they will respond. So, the mutuality involves being open to letting whatever is really going on in their settings loop back in to correct, modify, expand some of the things that we’ve been doing in the classroom. Our plan is to have a cohort of four advisors in each city; Bryan Stone and I will be two of those advisors, and then we would add two from each city, so that the cities have specific people that are still there after the grant ends. We want there to be available resources once the project ends.

We don't know what shape this project will ultimately take. So that opens the project up to a lot of creativity. We don’t even know what resources people are going to need, yet. So we're going to hear from them—what is it you have? What are the strengths and the resources you have, and what don’t you have? And could we respond to the gaps, the needs that we discover along the way, by providing some of resources? I think people don't have a lot of time to go looking for all sorts of resources. In a sense, the work of academics is curating the information. It's not telling people what they need! It's saying, “Oh have you thought about this? There’s this really cool thing happening in another part of the country.” There is a connectional component here—the ability to facilitate connectional learning in that sense that there’s a lot going on, but people tend to be unaware of what’s beyond their immediate orbit. The people on these advisory teams are aware of a broader conversation with various connections--what's happening in congregational studies, trauma studies—and will be able to share those conversations with congregational leaders. Of course, none of this has happened yet! We’re just imagining how it could turn out. But it is very exciting.

Amy: What kinds of things have you all been doing as a team to prepare for this project?

Shelly: We’ve had to slow down to cultivate the relationship with the advisory team. We have had some really important conversations around how we can support and draw in Spanish speaking congregations. That requires a whole lot of thinking about hospitality in terms of language provision and support. So, we are finding that even the setup of the project requires a kind of trauma awareness—a type of awareness that is required before we can move into talking about trauma with people, which involves gaining sensitivities around the topic, itself. So we've had to slow down, which I think is very important for where the congregations are right now. So hopefully by slowing down the process, we have made it more amenable to the congregational schedule.

Amy: Even though you are still in these beginning stages, what do you think might be the fruit of this labor? What do you think happens when churches grow in their capacity to respond well to trauma?

Shelly: I love that question. My hope is that we will no longer fear things coming to light—the things that are operative, but not visible. My hope is that congregations will not shy away from those difficult things but will feel strong in their ability to respond. I hope that these congregations will gain new awareness of how much people are carrying, and to develop, perhaps, countercultural responses. Trauma slows you down, and it is difficult work that not very many people want to tend to, or are equipped to tend to. So I think there is a prophetic dimension to doing trauma care, which is that you will enter into some of that uncertainty with people and guide them into a deep spirituality. I think that there is such a hunger right now for that spiritual accompaniment in the midst of all the things people are carrying. Churches ought to be able to step into that work. I think that congregations have always done work like this, but we are hoping to bring congregations into deeper awareness, deeper attention. I want these congregations to say we’re at our best when we are really bringing these difficult things to light—to give people the sense that it’s not too much to carry. There is a collective carrying that can take place. That is my hope.

Application deadline: September 30, 2021

Program duration: November 1, 2021 – April 30, 2023

Eligibility: Applicants’ congregations must be primarily located within the Atlanta, Boston, or San Diego Metropolitan Statistical Areas. Three congregations will be selected from each city, for a total of nine congregations. Each congregation applying must include a team of 3 individuals, one of whom must be in a significant leadership position (e.g., pastor, imam, etc.) and capable of eliciting congregational participation.

For more information, please see the project website: https://www.traumaresponsivecongregations.org/

The Counter-Cultural Impact of Intentional Communities and the Values that Shape Them

By Madison Boboltz

Imagine preparing a meal in your home, and then at the last second, without any notice, a stranger walks through the doorway. Without missing a beat, you set an extra spot at the table and welcome them to join you. Such an experience is not out of the ordinary during non-pandemic times at Beacon Hill Friends House, a Quaker-based nonprofit organization and intentional community located in Beacon Hill. At full capacity, the house holds up to twenty residents of religious and non-religious backgrounds who cultivate spaces to share in their lives and their work.

Residents of BHFH describe intentional community as a push against the tendency for people to separate themselves into individualized units— rather than close themselves off, they believe human life is enriched when people choose to open themselves (and their homes) to others. Some remarked that the cultural pressures to achieve independence is isolating. BHFH appealed to them because it is organized around hospitality driven values and commitments that residents not only agree to, but also put into practice. An unexpected dinner guest showing up at the house unannounced is therefore not perceived as an intrusion or inconvenience, but as a welcome addition and opportunity for connection.

Residents who favor this kind of lifestyle do not mean to convince everyone they encounter to sell their homes and adopt a similar living arrangement; instead, they hope to demonstrate to their communities that an alternative way of life such as theirs is not only possible, but also yields a number of potential benefits. One thing that makes BHFH unique, for example, is its physical location in an extremely affluent area. In many ways they might be considered the “weirdos on the block” who bring to Beacon Hill various groups of people who would typically not feel welcome there. Furthermore, because of their proximity to the state house, they are able to develop programming that invites members of the community to join with them in various forms of political action.

Boston University’s School of Theology provides a similar living experience for first year students. Theology House is located at 2 Raleigh St, just a fifteen minute walk from the School of Theology. Again, during non-pandemic times, residents share in weekly meals and spiritual programming, and the house often becomes a popular meeting place for events or gatherings that bring together other members of the STH community to join in meaningful fellowship with one another. Theology House demonstrates the transformative role of relationship-building in education and the vocational discernment process. In addition, it provides spaces in which STH’s community principles--love, justice, safety, rights, responsibilities, and respect-- may be cultivated and put into practice outside of the classroom.

In both Theology House and Beacon Hill Friends House, residents are not expected to belong to any faith tradition or share the same theology. The mission of these intentional communities rely on adherence to shared values, not beliefs. However, some intentional communities may be more theologically driven. For instance, one of the partner organizations for the Center of Practical Theology’s Creative Callings Project, St. Mary’s Episcopal Church in Dorchester, launched an intentional community called St. Mary’s House in September 2020. The goal for the house in its first year was to focus on the relationships between residents, a diverse group of individuals who were selected by the congregation after a two-year period of discernment. Having now achieved this foundational goal, members of St. Mary’s house hope going forward to strengthen the relationships between the house, the congregation, and the surrounding neighborhood. Some members of the house have taken to going on walks throughout the neighborhood, and have discovered through these outings some needs of their neighbors which the church has been helpful in meeting. It is their involvement with the church and their call to service which inspires residents to commit themselves to their community.

Beacon Hill Friends House, Theology House, and St. Mary’s House each engage in collaborative efforts to foster intentional communities that, to one degree or another, are counter-cultural. Independence does not necessitate isolation, nor does affluence necessitate exclusion. Education, particularly theological education, should not be focused exclusively on the academic competence of students, but also on their physical and spiritual well-being. One may build a home not to benefit themselves and meet their own needs, but to enrich their faith community and meet the needs of their neighbors. While tension and conflict inevitably arise in intentional communities, their ability to navigate those challenges and continue on in their missions demonstrate their creative potential and their admirable commitments.

Cultivating Community and Practical Wisdom through Spiritual Companioning Groups

By Britta Meiers Carlson

“For our opening practice today, I invite you to turn off your cameras and close your eyes. Let’s start by taking a deep breath as we come into the space together.”

At a time when so much of life happens virtually, encouragement to look away from the screen and simply exist in the body for a few moments can feel like a gift of grace. It is one of the many delights I experience in my teaching fellowship assignment as a Spiritual Companioning Group facilitator. These groups, which are integrated into the MDiv curriculum at Boston University School of Theology (STH), allow students to reflect on their own spiritual practices, learn from the practices of others, and develop strategies for building community and mutual support. Each semester, several STH PhD students facilitate these groups alongside the school’s Spiritual Life Coordinator, the Rev. Dr. Charlene Zuill, who also elegantly oversees the work of the facilitators. Each class session follows a standard format: an opening spiritual practice, a check-in, a guided discussion and/or dynamic activity, and a closing ritual. Facilitators serve as guides and mentors for students as they explore significant dimensions of their formation as theological and ministerial leaders.

While my other teaching fellowship appointments have allowed me to develop essential skills for teaching, such as lecture design and student evaluation, Spiritual Companioning Groups provide a unique opportunity to develop skills as a teacher of practical wisdom. In Christian Practical Wisdom: What it is and Why it Matters, the collaborating authors expand on notions of phronesis (“a kind of knowing that is morally attuned, rooted in a tradition that affirms the good, and driven toward aims that seek the good”) to define practical wisdom as a kind of knowing that incorporates the “cosmic and quotidian” dimensions of Christian tradition. (Bass et al., 11) The book encourages ministers and theologians to intentionally cultivate practical wisdom as a means of rebalancing the Enlightenment’s skew toward theoretical wisdom. (Bass et al., 10) Their work builds on earlier critiques of the theological academy. For example, Bonnie Miller-McLemore writes in Christian Theology in Practice: Discovering a Discipline that many theological educators have become convinced of the narrative, rooted in the work of Edward Farley, that the “clerical paradigm” is detrimental to theology; as a result of this assumption they have neglected to cultivate practical wisdom and connect it to practice in their scholarship and teaching. (Miller-McLemore, 182) This is a troubling trend in light of the reality that most of our students, especially those with ministerial vocations, will be expected to enact what they learn in seminary as leaders in communities of practice. Attention to the cultivation of our own practice, pedagogical approaches that emphasize praxis in the classroom, and explicit attention to “hints, tips, and rules of thumb” are assets that practical theologians bring to our research and to the communities in which we teach. (Miller McLemore, 197)

Spiritual Companioning Groups provide a space for the explicit cultivation of practical wisdom. This has been beneficial for my development as a teacher and helped me to discern how practical wisdom in the classroom dovetails and departs from my experience in the parish. In two semesters as a group facilitator, I have had the opportunity to design a practice-oriented syllabus, develop practices that cultivate community in a class setting, assess an appropriate balance of guest speaker-practitioners over the course of a semester, and mentor individual students who serve as co-facilitators for one class session. I have also developed multi-sensory strategies that provide students with opportunities to integrate what they are learning in their STH classes into their praxis.

Cultivating community through shared practice is an invaluable skill for responsible research and teaching in practical theology. Our research requires us to contemplate how practices constitute individuals and communities and to consider the contributions those individuals and communities make to theology. In teaching, we are accountable for the theological and ministerial development of students from a wide variety of places and experiences. As we engage this work, we inhabit a paradigm that is built on our life experiences, which include our racial and ethnic identity, economic status, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, family composition, nationality, citizenship status, professional and educational background, abilities, and level of health. While it is not possible for us to break out of our paradigm, shared spiritual practices may lead to relationships of trust and empathy that allow for responsible dialogue. In Taking on Practical Theology: The Idolization of Context and the Hope of Community, Dr. Courtney Goto, Associate Professor of Religious Education and Co-Director of the Center for Practical Theology, describes a critical intersubjective approach that enables researchers and members of faith communities to collaborate as they “co-construct knowledge of the faith community,” knowledge that emerges creatively in the space between researcher and collaborator(s). (Goto, 97) Attention to one’s paradigm, with particular focus on the limitations and blind spots created by one’s privilege within the paradigm, are indispensable for this approach. Professor Goto also models the effectiveness of building community through practices in the classroom in collaboration with Chris Schlauch, Associate Professor of Counseling Psychology and Religion and Psychology of Religion. I was privileged to take the course they co-teach, which embraces empathy as a strategy for relating across “paradigms of racism.”

In like manner, my experience with Spiritual Companioning Groups has revealed to me how nurturing a community can help students to be active participants in their own learning and that of their classmates as we co-construct the learning environment. At least once per semester, each student is encouraged to lead spiritual practices that have been meaningful to them throughout their life. They are also invited to share a “lifemap” that includes significant experiences that have shaped their spiritual development. Other students are then encouraged to share words of appreciation and to ask clarifying questions about the stories in order to deepen their insight about the constituting experiences of their peers. In witnessing the students’ final presentations, in which they share their perspectives on “spirituality” or “companioning,” I have been pleased to catch glimpses of the creative, dynamic, and intersubjective processes that bring about profound, integral learning in only 75 minutes a week for a semester.

The benefits of my appointment as a Spiritual Companioning Group facilitator come into particular focus when considering the realities of PhD work during the COVID-19 pandemic. At this stage of training, it is not unusual for a PhD student to become absorbed in our discipline and to anxiously strive to define our research focus; asserting oneself in the academy – the “paradigm” - necessarily involves immersion in highly specialized bodies of literature and theoretical frameworks. This deep absorption in our chosen areas of research can become particularly disengaged from any sphere of praxis as we are doing our work in greater isolation from faculty and peers than in pre-pandemic times. It is unreasonable to expect that we might be able to reproduce online the kind of dialectical learning we might do through casual interactions on campus, at conferences, or in faith communities. Other teaching fellowship opportunities, which might otherwise allow for more implicit gleanings toward pedagogy for practical wisdom, can easily become quite task oriented in the absence of the embodied community in a physical classroom. The intentional focus on spiritual practices that cultivate community and engage the senses throughout my time as a Spiritual Companioning Group facilitator has provided a surprising and welcome disruption from the haze of online independent research and virtual coursework. This experience has helped me to imagine the kind of interactive teaching and research that, I hope, will contribute to expanding notions of whose experiences matter in practical theology.

Fostering Holy Discontent and Re-creative Resistance: Towards a Virtù-esque Religious Pedagogy

A Response to Alexander Hanan’s Reimaging Liberal Education

Jennifer Lewis is a third year PhD student in Practical Theology at the School of Theology. In this CPT Today post, we highlight some of Lewis’s scholarship on religious education.

Alexander Hanan, in Reimagining Liberal Education, argues for an understanding of education that acknowledges and embraces its role in shaping the beliefs and ideas that inform persons’ actions in the world. Education, Hanan underscores, is always an agent of ethics; to suggest otherwise is to appeal to notions of neutrality that no longer stand in the face of critical theory(ies) and philosophy. Given its ethical orientation, Hanan proposes that liberal education today take up a “pedagogy of difference” that initiates persons into the moral vision and virtues of particular traditions while also tutoring them in “civic virtues” necessary for practicing democratic citizenship in a pluralistic society (161). Yet what are such virtues, and how “good” might they be? In the following, I briefly introduce Hanan’s basic understanding of education, problematize his argument for a pedagogy of difference based on virtue theory, examine the possibilities for a critical pedagogy for democracy, and conclude by pointing towards what I see as a more ethical and “virtù-esque” pedagogy.

To begin, then, Hanan understands education as involving “initiation into communities in pursuit of worthwhile knowledge (141).” Such a definition assumes that one holds to a conception of what is “worth knowing” and, therefore, a “concept of the good life,” since one’s vision of the good invariably shapes one’s conceptions of “worthwhile knowledge” (141). A pedagogy of difference, it follows, seeks to introduce learners into the particular concepts of “the good” that belong to their religio-cultural traditions while helping them develop the autonomy and “moral intelligence” to judge between and respect other ways of life (3).

Hanan’s basic concept of education rests on three assumptions. The first is that reason is never neutral. All inquiry, for Hanan, is situated, guided by and pulled towards, in part, by one’s vision of the “good life”, of the life “worth living”, which itself is rooted in a set of values and beliefs. In other words, there is no disinterested mode of inquiry, which means that education is always an education in values, an education in ethics. Hanan’s second assumption builds on the fallacy of objectivity. Given the non-neutrality of all reasoning, Hanan assumes that education for life in pluralistic societies requires literacy in “thick” traditions, namely “robust and detailed cultural narratives, symbols, and artifacts that reflect the complexities and perplexities of real life…” (158). Such an education into particular traditions presumably equips persons to better exercise autonomy and agency – namely, self-determination, self-expression, and self-evaluation – because it enables them to develop the “moral intelligence” needed for evaluating between ways of life (159) in the absence of a “common rationality that can serve as a neutral meeting ground” (135). This leads to Hanan’s final assumption: namely, that making evaluative judgements and exercising critique first requires that one possess “strong subjectivity”, by which he means “second-order desires” about who one desires to be (135). By educating persons in “thick” traditions that possess “strong” values, they can develop a “sense of responsibility and accountability” that, in turn, helps them discern the kind of persons they want to be (159).

The problem with Hanan’s argument is that “cultivating the authentic self that democracy requires” requires an interrogation of the traditions – political and religio-cultural – upon which democracy and one’s traditions depend. In other words, a person cannot practice “authenticity” nor democracy unless she is also asking questions about the non-neutral assumptions, values, and visions that have informed the political and religious/moral virtues she is supposed to cultivate. It is somewhat ironic, given Hanan’s emphasis on the non-neturality of all reasoning, that he fails to recognize the non-neutrality of notions of “character and virtue” (c.f. 167-168). “Goodness”, like reason, is always particular, but its particularity does not mean it is “good.” Hanan’s affirmation of “expansive” character education completely bypasses the non-neutrality of political and religious/moral “virtues,” which have been and continue to be deployed in ways that suppress autonomy, encourage civility and consensus in place of conflict, and stifle creativity and human potentiality (such has been the case with women and minorities). Contra Hanan, then, I would argue that any education for democratic engagement today must not make a “virtue” of assuming the goodness or uniformity of “virtues.” On the contrary, we must make a virtue of “virtù”: namely, the practice of continually contesting, questioning, intervening and augmenting traditions and discourses, with a view to enhancing political and particular – particularly religious - life.

Critical pedagogy is particularly necessary in this regard, though Hanan’s critique of critical pedagogy caricatures its educational intentions. Critical pedagogues, contra Hanan, do not seek to indoctrinate persons into a “new ideology of liberation or exposed hegemonic discourse (152).” Rather, critical pedagogy seeks to tutor learners in a practice of critique and attentiveness to power, inequality, and domination in order to create the possibility for choice. In other words, critical pedagogy takes for granted that persons enter into the educational process with value-systems and narratives about human flourishing, good and bad, right and wrong. Learners may or may not be aware of these value-systems and narratives, and some may have more sedimented moral assumptions than others. At the same time, critical pedagogy assumes that it is not possible to enter public education or any educational process without some working narrative of reality. Given this, the aim of education is not to tutor persons in a particular set of “civic”, cultural, or religious values but to equip them to recognize the gaps, silences, and oppressive potentiality of all discourses in order that they can re-cognize – namely, re-narrate, re-commit to, or re-conceive of - the traditions, narratives, and values they hold dear. Such a pedagogy employs a “hermeneutics of suspicion” for the sake of empowering persons to more fully authenticate, choose, and thus possess and express the criteria upon which they discern how they want to live in the world. In this sense, critical pedagogy fulfills all three criteria of human agency Hanan describes: “self-determination, self-expression, and self-evaluation” (142).

Of course, Hanan argues conversely. Yet, the reason, in part, that Hanan reaches the opposite conclusion – namely, that critical pedagogy suppresses the above elements of human agency - is that he creates a false dichotomy between critical pedagogy’s emphasis on conscientization and the interests of a “particular child” (153). He argues,

By advocating that children ought to be liberated from or made conscious of hegemonic culture in order to serve ideological interests or new discourses they may not necessarily embrace, radical curriculum theory employs such terms as ideology and discourse in an amoral sense; and since all truths and values are relative to class, culture, race, or gender…there is no way to assess whether the interests of a particular child…are in fact being served by this new ideology of liberation or exposed hegemonic discourse (153).

One of the several problems with this sentence – and Hanan’s larger dismissal of critical pedagogy – is that it inaccurately conceptualizes what critical pedagogy seeks to do. Critical pedagogy is not interested in co-opting learners’ agency to “serve ideological interests or new discourses” nor does it uniformly aim to dismantle all narratives so that people can live value-free, or, conversely, take up values that do not align with their personal commitments or beliefs. On the contrary, the practices of questioning and exposing allow for the un-covering of aspects of domination and exploitation in cultures, traditions, and modes of education and thus serve as tools by which one can make more conscious choices, imagine alternative ways of living, and develop one’s own value, whether those of one’s “tradition of origin” or other sources. In this sense, critical pedagogy, while it prioritizes un-covering the incongruities and power dynamics at play in our discourses, dismantles for the purpose of re-mantling, though in ways that are partial and preliminary rather than universalistic.

In sum, Hanan’s argument that critical pedagogy indoctrinates and therefore undermines human agency does not make any sense. Yes, critical pedagogy makes normative assumptions about the “good life”, particularly as it connects to “liberation”, by which most mean conscientization and empowerment for choice and action. Yet, I imagine many would, much like feminist pedagogues, happily “own” the subjective and normative impulses of their educational philosophy, especially given that one can only fully embrace agency if she is aware of the circumstances that condition her actions or knowledge. In fact, it is ironic that critical pedagogy’s practice of critique and exposure, which are inextricably tied to its assumptions about “the good life” – namely, that persons can and ought to be able to choose ways of life that do not lead to the silencing and oppression of other ways of life – aligns with the assumptions that energize Hanan’s work.

That said, I resonate – to a degree – with Hanan’s fear that “radical curriculum” does not sufficiently help students challenge, affirm, extend, or even realize the values and moral assumptions that shape their identities and inform their choices. In prioritizing the work of unveiling elements of inequality, oppression, and erasures in dominant discourses, critical pedagogies often leave little room for the self-reflection and re-constructions of moral values that are not only necessary for living in a pluralistic world but also invariably influence one’s perceptions and actions, whether one concedes to it or not. Moreover, many versions of critical education exhibit a tendency to dismiss certain narratives, traditions, and cultural practices as fundamentally opposed to the project of liberation, especially those institutionalized and majority religious traditions. The problem with this, besides the obvious overgeneralization, is that critical pedagogy often dismisses such traditions without 1) attending to the particularity and plurality of religious praxis and 2) recognizing that the multiplicity, tensions, and conflicting discourses and resistances within such traditions are sources of its vitality and catalysts for its augmentation.

Yet, I do not think Hanan’s proposal – a “pedagogy of difference” that cultivates “intelligent spirituality” for the sake of “peaceful co-existence – fully addresses either of the above issues while also cultivating the kind of critical self and communal attentiveness to issues of domination and manipulation in traditions, cultures, and politics that obstruct freedom. I also think that Hanan’s approach leads to a more passive orientation towards public life than is necessary for democracy’s preservation. Rather than equipping learners to influence and re-shape the relations and institutions that shape life in a pluralistic world, Hanan’s approach valorizes “peaceful co-existence” without clarifying what such peace looks like and on whose terms.

So where does this leave us? If we take Hanan’s claim seriously – that education is an agent of ethics – while rejecting his pedagogy of difference, then what kind of religious education can best equip persons to lead “ethical” lives? Building on Bonnie Honig’s notion of virtù politics, which encourages person to seeks out the silence, gaps, fissures, resistances, and “unruly elements” of private and public narratives and values with the purpose of augmenting and re-birthing them, I argue for a pedagogy of “holy discontent and re-creative resistance” that bring together practices of unknowing and re-creating reflected in the apophatic and kataphatic modes of the contemplative life. Specifically, such a pedagogy would connect Nietzsche’s call for “self-responsibility” and Arendt’s notions of “action” and “authority” - two vital practices for political life – with two contemplative modes of religious learning - apophaticism and kataphaticism – with the aim of equipping persons for continually resisting and re-creating notions of “virtue” in both the religious and public realm. Cycles of remembering, unknowing, resisting, disrupting, undoing – the apophatic – would be paired with practices of re-cognizing, re-constructing, re-creating, and cultivating response-ability – the kataphatic – in order to advance the self-responsibility, action, and authority characteristic of virtù politics. Thus rather than cultivate classical and “civic” virtues, such a pedagogy would tutor learners in postures - agrupnia, aphobia, humility, holy listening, holy indifference, and holy foolishness - that simultaneously equip them to seek out “fissures” and “silences” in public life, theological narratives, and self, while also providing them the self-reflection and communal affirmations, for re-birthing them and the virtues that can re-vitalize the public and religious realms.

Opportunities to Reengage: Upcoming Conferences

As vaccines are distributed across the country, academics are beginning to reemerge from their Covid isolation. Many of us are eager to attend conferences, listen to the latest research, and to reconnect with peers and colleagues. CPT Today would like to highlight some of the upcoming conferences and events that we can look forward to during the summer and through the fall. We invite our readers to pass along any information pertaining to upcoming opportunities so that we can update this post accordingly. Please contact cpt@bu.edu with the name, date, and location of the event or conference you wish to share with us. The following conferences feature sessions that may interest students and scholars of Practical Theology.

The Northeast Regions of the AAR present: A Virtual Symposium

Online - April 9, 2021

(https://www.symposium2021.com)

Registration is open for this one-day, online symposium, jointly hosted by the Northeast regions of the American Academy of Religion. In lieu of individual regional meetings, this joint symposium will offer a wealth of scholarship from all across the Northeast, including keynote sessions from Mayra Rivera and Marla Frederick.

The Thomas H. Olbricht Christian Scholars’ Conference

Nashville, TN - June 9-11, 2021

(https://christianscholarsconference.org)

This conference features a wide range of interdisciplinary conversations, and includes a session on Practical Theology. While the Call for Papers is rather limited this year (due to Covid complications), this year promises to offer an exciting array of academic presentations relating to the conference theme, Recovery of Hope: A Vision for Healing, Trust, and Restitution.

The joint SBL/AAR Annual Meeting

San Antonio, TX - November 20-23, 2021

(https://www.sbl-site.org/meetings/AnnualMeeting.aspx)

(https://aar-conference.imis-inspire.com/a/)

This joint conference for the American Academy of Religion and the Society of Biblical Literature hosts an unbelievably diverse range of sessions, many of which may appeal to Practical Theologians. While the American Academy of Religion’s CFP is now closed, some may be interested in attending a co-sponsored session, hosted by the AAR Practical Theology Unit and the Association for Practical Theology titled “Learnings from the pandemic: Implications of Adapting and Inventing Ecclesial Practices for COVID” (https://aar-conference.imis-inspire.com/a/page/ProgramUnits/co-sponsored-session-pt-apt).

The Society of Biblical Literature’s CFP does not close until March 23. For those who are interested, CFPs have been posted for the Bible and Practical Theology session (https://www.sbl-site.org/meetings/Congresses_CallForPaperDetails.aspx?MeetingId=39&VolunteerUnitId=478), as well as the Homiletics and Biblical Studies session (https://www.sbl-site.org/meetings/Congresses_CallForPaperDetails.aspx?MeetingId=39&VolunteerUnitId=286).

The Academy of Homiletics Annual Meeting

Chicago, IL – December 2-4, 2021

The annual meeting for the Academy of Homiletics is only open to members of the Academy of Homiletics. However, doctoral students studying homiletics can apply to join the Academy here: http://www.homiletics.org. The theme for this year’s meeting is “A Celebration of African American Preaching.”

The Center for Practical Theology’s Thirteenth Annual Lecture with Dr. Heather Walton

We were thrilled to welcome University of Glasgow's Dr. Heather Walton to give the Center for Practical Theology’s Thirteenth Annual Lecture on December 4, 2020. Dr. Walton presented “Body and Stone: Practical Theology as Creative Work,” and Boston University School of Theology’s Lecturer in Practical Theology Dr. Callid Keefe-Perry responded to the lecture.

We were thrilled to welcome University of Glasgow's Dr. Heather Walton to give the Center for Practical Theology’s Thirteenth Annual Lecture on December 4, 2020. Dr. Walton presented “Body and Stone: Practical Theology as Creative Work,” and Boston University School of Theology’s Lecturer in Practical Theology Dr. Callid Keefe-Perry responded to the lecture.

We were pleased to welcome our colleagues from BU School of Theology, Boston Theological Institute schools, and from the greater community. The video is available here. We are so grateful to Dr. Walton for sharing her insights with us.

Below, PhD Student in Practical Theology, Vaughn Nelson, responds to Dr. Walton’s lecture.

By Vaughn Nelson

As is now (almost) routine, attendees of the 13th Annual Lecture for the Center for Practical Theology gathered virtually on December 4, 2020, to hear from Dr. Heather Walton on the theme “Body and Stone: Practical Theology as Creative Work.” Dr. Walton has contributed deeply to the field of Practical Theology over several decades, and she is currently Professor of Theology and Creative Practice at the University of Glasgow School of Critical Studies. So, she is well positioned to reflect on the present state of practical theology as a discipline.

As is now (almost) routine, attendees of the 13th Annual Lecture for the Center for Practical Theology gathered virtually on December 4, 2020, to hear from Dr. Heather Walton on the theme “Body and Stone: Practical Theology as Creative Work.” Dr. Walton has contributed deeply to the field of Practical Theology over several decades, and she is currently Professor of Theology and Creative Practice at the University of Glasgow School of Critical Studies. So, she is well positioned to reflect on the present state of practical theology as a discipline.

As Dr. Callid Keefe-Perry, PhD grad and newly appointed lecturer at STH, summarized in his response, Dr. Walton asks us to imagine what might be possible in Practical Theology if we put as much effort in developing aesthetic and creative capacities as we do in learning empirical research methods. What if, she wonders, Johannes van der Ven had declared forty years ago, not (only) that theology must become empirical, but (also) that theology must be creative? To be clear, she does not wish to undo the many gifts that the empirical and social scientific turns have offered Practical Theology, and she also confesses both her own “complicity” in and benefiting from the growing importance of these methods and methodologies. However, she does wish to name a concern that when social scientific enquiry becomes synonymous with Practical Theology, this disguises a move away from doing theology. Even as she wishes for the deconstructive blurring of many boundaries and binaries in the discipline (theory/practice, art/science, primary/secondary theology), she remains quite confident that if we are, in fact, theologians at all, then we have a responsibility to do something with our findings—something theological, creative, constructive.

It so happened that I logged on to Dr. Walton’s lecture while taking a break from the final weekend of writing my term paper in the Practical Theology doctoral seminar. This was, on the one hand, an unfortunate excuse for the always-lurking self-doubt to surface in that crucial final push toward any paper deadline (Am I doing the very things she’s critiquing?). On the other hand, I had method and meta-discipline on my mind, and the lecture and response hinted at the exciting beyond in this field in which I’m being formed—beyond coursework, beyond practical theology’s past and present. I appreciate Dr. Walton’s acknowledgment of the empirical turn’s gifts. Like so many of my fellow doctoral students, I have sought a home in practical theology because of the serious—read: social scientific—attention it gives to practice, experience, lived religion, and the ways this focus resonates with liberative theologies’ priority of praxis as locus theologicus. Yet, I also echo her desire that words like ‘aesthetics,’ ‘creativity,’ and ‘imagination’ be treated with the same seriousness. Listening to Dr. Walton, I was aware of an unexpected tension that has emerged in my second year of this degree: after becoming enchanted with the theological writing of Mayra Rivera in Poetics of the Flesh and Sharon Betcher in Spirit and the Obligation of Social Flesh, it is more difficult than I expected to integrate such enfleshed theology with my “research interests,” to know what to do with theology like theirs in a practical theological mode. I suspect this has much to do with the educational stage in which I find myself, but I am making note that something about the way we celebrate the empirical in practical theology seems to make it just a bit more difficult to locate the place for poetic theory-laden theological writing.

Fortunately, my new educational home here at STH shares, I sense, Dr. Walton’s hopes. While listening, I thought of my first Teaching Fellow assignment in Dr. Courtney Goto’s “Doing Theology Aesthetically” summer intensive course. Student made creative theological contributions, not only by reflecting on various art activities, but also by reflecting and expressing through such forms. An important question I will carry with me into further theological, teaching, and ministry contexts is, “What can a particular aesthetic experience say, theologically, that words cannot?” I also had in mind Dr. David Jacobsen’s passionate insistence in our doctoral seminar that practical theology is, in the end, lest we forget, theology. Dr. Walton would be pleased. Paired together, even just these two notions are challenging and inspiring. Practical Theologians, with all our careful, self-reflexive accounting of experience, ought to have something say—about God, about the world, and about their entanglements—and some things can best be said, or perhaps only be said, through aesthetic expression.

For her part, Dr. Walton attended to the form of her lecture as much as the content. She would speak, she promised, like a good preacher, in three parts—with points and illustrations. Before each part she repeated a variation on a litany that began, “Before I open my mouth to speak . . .” The opening third of her lecture consisted of excerpts from recent journal entries reflecting on her experience of the “troubles” (Donna Haraway) of recent months—time she spent on the east coast of Scotland, since remote teaching allowed such a change of scenery. These reflections then became entry points for critical engagement with the discipline of practical theology as the middle section. Finally, she offered us word images from those journal entries as “pebbles from the beach” where her reflections take place—imaginings of what might be in the beyond of practical theology. In Dr. Walton’s hands, life writing, in this case at least, is less the data she mines for qualitative themes, and more a capacious holder for expressions that do not have an obvious fit in the usual theological or methodological categories. (“Everything can fit in here: emotions are allowed, the body has entry, you can talk to God and to yourself and to others.”) Citing Dr. Claire Wolfteich’s influence, she says that for just this reason, her journals are an emerging source for her theology. Which leads me to wonder not only what this particular form of expression might say, theologically, that other forms cannot, but also what theologically potent forms we have yet to lend our ears, our eyes, or our touch. How might we, practical theologians, be positioned to help name and attend to those forms? Imaginative responses are, I gather, welcome.

Vaughn Nelson is a second-year PhD Student in Practical Theology, studying Religious Education as a source for embodied, liberative, and decolonizing pedagogies for navigating spirituality in (post)secular, pluralist contexts. He draws on liberation and postcolonial theologies, critical theories of disability and embodiment, theories of practices, and theories and research methods from the sociology of religion.

Practical Theology Students to Participate in This Year’s AAR-SBL Annual Meeting

Due to the ongoing serious threat of Covid-19, this year’s annual joint meeting for the American Academy of Religion and the Society of Biblical Literature will be taking place entirely online. And although the meeting was initially set to take place here in Boston, the virtual nature of this year’s conference will allow what is one of the world’s largest gatherings of theologians and scholars of religion to take place without posing a health risk. The Center for Practical Theology will be well represented this year by a few of our own students, whose paper and session titles are listed below. Please join us in congratulating Dan Hauge, Britta Carlson, and Kate Common!

Due to the ongoing serious threat of Covid-19, this year’s annual joint meeting for the American Academy of Religion and the Society of Biblical Literature will be taking place entirely online. And although the meeting was initially set to take place here in Boston, the virtual nature of this year’s conference will allow what is one of the world’s largest gatherings of theologians and scholars of religion to take place without posing a health risk. The Center for Practical Theology will be well represented this year by a few of our own students, whose paper and session titles are listed below. Please join us in congratulating Dan Hauge, Britta Carlson, and Kate Common!

Daniel Hauge

Daniel Hauge

“Comfortable White Affect as Colonial Practice, and the Oppressive Power of Norms”

Unit: Practical Theology

Theme: Decoloniality, Religious Practices, and Practical Theology

Britta Meiers Carlson

Britta Meiers Carlson

“Striving to be Mainline: White Performativity as a Barrier to Equity and Diversity in U.S. Progressive Christian Denominations”

Unit: Practical Theology

Theme: Decoloniality, Religious Practices, and Practical Theology

Kathryn Common

Kathryn Common

Panelist

Unit: Women’s Caucus

Theme: AAR/SBL Women’s Caucus Business Meeting