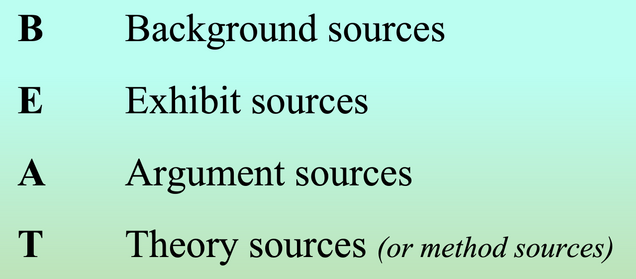

The image above defines the BEAM/BEAT taxonomy: Background, Exhibit, Argument, and Method (or Theory).

by Joseph Bizup

Introduction to BEAM/BEAT: A Functional Vocabulary

- Background sources provide uncontested information that sets up an argument. Background sources are materials whose claims a writer puts forward as background information. Writers regard information from their background sources as authoritative and non-controversial, and they expect their readers to do the same. Because writers sometimes treat information gleaned from their background sources as “common knowledge,” they may sometimes leave these sources uncited.

- Exhibit sources provide evidence and material for analysis or interpretation. Exhibit sources are materials a writer offers for explication, analysis, or interpretation. Materials used as background, argument, or theory/method sources tend to be prose texts, but anything that can be represented in discourse can potentially serve as an exhibit. The simplest exhibits are examples, concrete instances offered to support or illustrate some more general claim or assertion. The term “exhibit” is not synonymous with the conventional “evidence,” which designates data offered in support of a claim. Exhibits can lend support to claims, but they can also provide occasions for claims. Complex exhibits can demand extensive framing and interpretation. Understood in this way, the exhibits in a piece of writing work much like the exhibits in a museum or a trial. Good writers, like good curators and lawyers, know that rich exhibits may be subjected to multiple and perhaps even conflicting “readings.” They know they must do rhetorical work to establish their exhibits’ meanings and significance.

- Argument sources provide claims the writer engages in some way. Argument sources are materials whose claims a writer affirms, disputes, refines, or extends in some way. To invoke a common metaphor, argument sources are those with which writers enter into “conversation.” In professional academic writing, there is a strong correlation between the genres in which writers work and the genres of their argument sources, but this correlation is weaker in student writing. In the ordinary practice of their professions, historians generally write articles and books that engage articles and books by other historians; neuroscientists generally write research reports that engage research reports by other neuroscientists. Students are not regularly asked to write papers that engage other student papers. This “genre gap” may be a significant reason students sometimes fail to apprehend the dialogic nature of academic argumentation.

- Theory (or Method) Sources provide a method, model, vocabulary, or approach. Theory (or method) sources are materials from which a writer derives a governing concept or a manner of working. A theory source can offer a set of key terms, lay out a particular procedure, or furnish a general model or perspective. Like background sources, theory sources can sometimes go uncited, for at least two reasons. It is not unusual for writers to acknowledge their most important theory sources only obliquely, by deftly dropping a recognizable name, using a particular terminology, or adopting a prose style or mode of exposition that affiliates them with a particular school of thought. Likewise, especially influential concepts or methods may enter into the general parlance of disciplines or professions and so lose their ties to specific sources. (Note: The alternate terms “method” and “method source” are sometimes more intuitive for writers working in certain fields, particularly the sciences.)

BEAM/BEAT in practice: Planning syllabi and assignments

BEAM/BEAT: Multiple Uses for Teachers, Students, and Librarians

BEAM/BEAT vs. Traditional Vocabulary for Sources

- works for some disciplines (history, literary criticism) but not at all for others

- conflates genre and function

- serves researchers in particular fields, not writers.

When teaching students how to write with sources, we need a nomenclature that allows us to talk directly and straightforwardly about how writers use their sources on the page. BEAM/BEAT’s main advantage over the standard nomenclature is that it allows us to describe writers’ materials straightforwardly in terms of what writers do with them: writers rely on background sources, interpret or analyze exhibits, engage arguments, and follow or invoke theory sources.

Literary-critical examples of BEAM/BEAT

- Consider the way Miller uses sources throughout “Discipline in Different Voices” (The Novel and the Police, University of California Press, 1988):

- Background: David Roberts, The Victorian Origins of the Welfare State.

- Exhibit: Charles Dickens, Bleak House

- Arguments: Critical essays by J. Hillis Miller, Terry Eagleton, etc.

- Theory: Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish

- Look at the following annotated passage from Freedgood (pp. 5-6 in The Ideas in Things: Fugitive Meaning in the Victorian Novel, University of Chicago Press, 2006.):

And my choice of objects [Exhibit Sources] is influenced by structures of thoughts and feeling that derives from a line of critical thinking that could be traced from Marxist cultural studies, the study of culture and imperialism, postcolonial theory, and studies of power and subjectivity from Franz Fanon and Sigmund Freud to Michel Foucault and Judith Butler. [Theory Sources] The result is the method of the first three chapters of this book: one in which the historically and theoretically overdetermined material characteristics of objects are sought out beyond the immediate context in which they appear. These objects are then returned to their novelistic homes [Jane Eyre, Mary Barton, Great Expectations, Middlemarch] [Exhibit Sources], so that they can inhabit them with a radiance or resonance of meaning they have not possessed or not legitimately possessed in previous literary-critical reading [Argument Sources].

Resources for Teaching

- Acknowledgment and Response

- BEAM/BEAT: Rhetorical Ways of Thinking About Sources

- Close Reading Exercise

- Developing Key Terms

- Formulating Questions and Claims Based on Observations

- Picture Prompts for Online Classes

- Reading for Research

- Research as Forming a New Question

- Sample WR 120/15x Assignment: Academic Paper on an Outside-of-Class Experience

- Strategies for Analysis of Text

- Strategies for Engaging with Critics

- Summary & Analysis

- Teaching with the WR Journal: Volume 10 (2018)

- Use a Text as a Theory Source

- Using Different Kinds of Sources to Analyze an Exhibit