Spot the Difference: Comparing the Belt Road Initiative and the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment

By Oyintarelado Moses, Anjali Kini and Keren Zhu

The Group of 20 (G20) meetings are taking place in Indonesia this week, and top agenda items include financial stability and sustainable development. Infrastructure finance gaps in the Global South have widened in recent years as pressing demands to address connectivity bottlenecks and climate-related challenges have increased. To reach the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), an additional $3.2 trillion or 2 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) is needed annually for sustainable infrastructure investment, and roughly $700 billion per year of climate finance is required to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

Global infrastructure initiatives such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), an infrastructure-led international economic engagement initiative, and the Group of Seven (G7)-led Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), an infrastructure partnership that aims to address infrastructure gaps of low- to middle-income countries, are positioned to further address these financing gaps.

What are the key similarities and differences between the BRI and the PGII? And how can the BRI and the PGII fill the infrastructure financing gaps in the Global South?

A new working paper provides an overview of the BRI and the PGII, comparing their features to determine to how the initiatives could complement one another and offer effective options to recipient countries.

The BRI was established in 2013 under the main objectives of policy coordination, facility connectivity, financial integration, unimpeded trade and people-to-people bonds. Through the BRI, China leverages its competitive advantage in industrial capacity and infrastructure development which further facilitates the expansion of Chinese firms into international markets. As of 2021, 145 countries and 32 international organizations have become partners under the BRI framework. According to the China’s Overseas Development Finance (CODF) Database, managed by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, from 2013-2019, Chinese policy banks loaned at least $287 billion to host countries for development projects. China’s overseas development investment funds (ODIFs) have already invested portions of their full potential capacity of $155 billion in equity finance for development projects. This level of funding under the BRI framework has supported host countries in correcting infrastructure bottlenecks, promoting trade and future prosperity. However, projects under the BRI face certain drawbacks such as socio-environmental risks, financial risks, and governance and corruption challenges in partner states. Nevertheless, the BRI furthers Chinese lenders’ and investors’ outreach on a global scale and addresses host countries’ developmental needs.

The PGII was established in 2022 at the 47th G7 leadership summit to address infrastructure gaps of low- and middle-income countries for the climate, health and health security, digital technology and gender equity and equality areas. The PGII also incorporates the Global Gateway (GG), a European Union (EU) initiative announced in 2021 to address global investment gaps and support a global recovery from the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Leaders from Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Italy, the United Kingdom, the United States and the EU pledged $600 billion for PGII and characterized it as a relaunch of the Build Back Better World Partnership (B3W), announced in 2021. These countries’ policy banks, commercial banks, state insurance agencies and other development assistance-related will coordinate efforts to achieve the pledge, under a more focused, coordinated and targeted domestic and multilateral strategy for supporting overseas infrastructure development. The PGII’s financial scope is smaller compared to the BRI. While the US development assistance institutions have a full financing capacity of $196 billion, projects under the PGII have received $1.8 billion in US loans, grants and equity commitments as of June 2022. In the case of GG, $21.1 billion has been committed towards various projects in Africa and Europe. If successful, the PGII could be an attractive option for recipient countries due to the framework’s underlying strong regulatory, social, environmental, transparency and accountability standards.

Although the BRI and the PGII were established in different years and under different global economic circumstances, the initiatives share similarities. First, both initiatives focus on infrastructure development in low- and middle-income countries and are currently prioritizing green projects. Second, both initiatives were announced as initiatives of intent, but as their governments developed guidelines, the initiatives moved to implementation. Although the BRI was announced in 2013, specific guidelines for implementation were not released until 2015. Similarly, the PGII was initially packaged as the B3W in 2021, but when relaunched as the PGII, the initiative had more concrete goals and plans for coordination. Third, both initiatives rebranded existing development assistance efforts. Just as China’s policy banks maintained the same mandates to support Chinese companies and exports before and after the BRI, G7 financing institutions are still fulfilling their mandates, while branding their efforts as contributing to the PGII. Fourth, China and the G7 are using their public financing institutions (e.g., policy banks, public insurance aid agencies) to support their countries’ corporations and investors supporting overseas development projects. Collectively, both initiatives aim to bolster domestic growth within China and G7 countries through supporting the corporate actors that expand market share in recipient countries with the support of development finance.

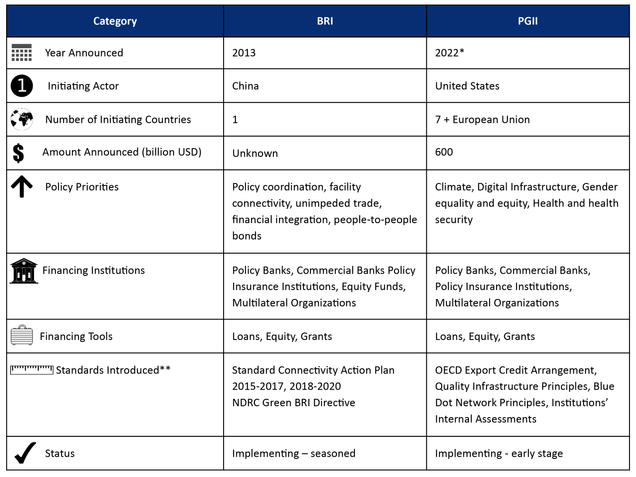

Table 1: Comparing the BRI and the PGII

*Although the PGII was established in 2022, its predecessor, the B3W was established in 2021.

**Not an exhaustive list of standards introduced.

On the other hand, the BRI and the PGII also differ in significant ways. The BRI has largely supported “hard” infrastructure projects such as ports, roads, dams, railways, electric power plants and telecommunication facilities due to China’s comparative advantage in cost and project turnover in traditional infrastructure. Some of these projects have required substantial amounts of capital, and China’s policy banks have financially supported such large projects with limited success with leveraging private capital. In contrast, the PGII appears to target “soft” infrastructure projects, namely improvements in climate, health and health security, modernized digital technology and gender equity and equality. These project types are financed through smaller amounts of public finance that is meant to catalyze the involvement of the private sector. Each initiative also approaches coordination differently. China’s Belt and Road Construction Leadership Group appears to lead coordination between BRI institutions, while the PGII has yet to generate an overarching coordination mechanism across all G7 countries that builds on domestic institutional coordination.

Given such similarities and differences, the BRI and PGII should consider collaboration in the short- and long-term. If collaboration is not feasible in the short-term, BRI and PGII institutions should consider complementary competition. Within collaboration, institutions of these initiatives could learn from one another’s comparative advantages and support different aspects of the same project based on their competitive edge. Within complementary competition, institutions should not compete solely on the most bankable or less risky deals but spread their capital across a diverse set of projects that leverage their comparative advantages while strengthening risk mitigation practices. Additionally, BRI and PGII institutions can focus on collaborating more with host regional financing institutions and prioritize recipient countries’ development assistance demands. Rather than feeling “forced to choose,” recipient countries should participate in both initiatives and leverage the differences in the initiatives to negotiate the best deal for their development projects.

Currently, the BRI is undergoing recalibration as China addresses a moment of internal economic flux and feedback it has received on BRI projects with challenges, while the PGII is suffering from reputation risks and the challenge of fully catalyzing private sector involvement in the current global economic environment. Amidst such challenges, the prospects of the two initiatives are particularly concerning given the existing infrastructure and sustainability finance gaps that remain. It is imperative that countries and institutions within the BRI and PGII continue to encourage the development of these initiatives.

Read the Working Paper*

Anjali Kini is a Research Assistant with the Boston University Global Development Policy Center and an MA Candidate in Global Development Economics at Boston University.

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global China Initiative Newsletter.