Cultivating Community and Practical Wisdom through Spiritual Companioning Groups

By Britta Meiers Carlson

“For our opening practice today, I invite you to turn off your cameras and close your eyes. Let’s start by taking a deep breath as we come into the space together.”

At a time when so much of life happens virtually, encouragement to look away from the screen and simply exist in the body for a few moments can feel like a gift of grace. It is one of the many delights I experience in my teaching fellowship assignment as a Spiritual Companioning Group facilitator. These groups, which are integrated into the MDiv curriculum at Boston University School of Theology (STH), allow students to reflect on their own spiritual practices, learn from the practices of others, and develop strategies for building community and mutual support. Each semester, several STH PhD students facilitate these groups alongside the school’s Spiritual Life Coordinator, the Rev. Dr. Charlene Zuill, who also elegantly oversees the work of the facilitators. Each class session follows a standard format: an opening spiritual practice, a check-in, a guided discussion and/or dynamic activity, and a closing ritual. Facilitators serve as guides and mentors for students as they explore significant dimensions of their formation as theological and ministerial leaders.

While my other teaching fellowship appointments have allowed me to develop essential skills for teaching, such as lecture design and student evaluation, Spiritual Companioning Groups provide a unique opportunity to develop skills as a teacher of practical wisdom. In Christian Practical Wisdom: What it is and Why it Matters, the collaborating authors expand on notions of phronesis (“a kind of knowing that is morally attuned, rooted in a tradition that affirms the good, and driven toward aims that seek the good”) to define practical wisdom as a kind of knowing that incorporates the “cosmic and quotidian” dimensions of Christian tradition. (Bass et al., 11) The book encourages ministers and theologians to intentionally cultivate practical wisdom as a means of rebalancing the Enlightenment’s skew toward theoretical wisdom. (Bass et al., 10) Their work builds on earlier critiques of the theological academy. For example, Bonnie Miller-McLemore writes in Christian Theology in Practice: Discovering a Discipline that many theological educators have become convinced of the narrative, rooted in the work of Edward Farley, that the “clerical paradigm” is detrimental to theology; as a result of this assumption they have neglected to cultivate practical wisdom and connect it to practice in their scholarship and teaching. (Miller-McLemore, 182) This is a troubling trend in light of the reality that most of our students, especially those with ministerial vocations, will be expected to enact what they learn in seminary as leaders in communities of practice. Attention to the cultivation of our own practice, pedagogical approaches that emphasize praxis in the classroom, and explicit attention to “hints, tips, and rules of thumb” are assets that practical theologians bring to our research and to the communities in which we teach. (Miller McLemore, 197)

Spiritual Companioning Groups provide a space for the explicit cultivation of practical wisdom. This has been beneficial for my development as a teacher and helped me to discern how practical wisdom in the classroom dovetails and departs from my experience in the parish. In two semesters as a group facilitator, I have had the opportunity to design a practice-oriented syllabus, develop practices that cultivate community in a class setting, assess an appropriate balance of guest speaker-practitioners over the course of a semester, and mentor individual students who serve as co-facilitators for one class session. I have also developed multi-sensory strategies that provide students with opportunities to integrate what they are learning in their STH classes into their praxis.

Cultivating community through shared practice is an invaluable skill for responsible research and teaching in practical theology. Our research requires us to contemplate how practices constitute individuals and communities and to consider the contributions those individuals and communities make to theology. In teaching, we are accountable for the theological and ministerial development of students from a wide variety of places and experiences. As we engage this work, we inhabit a paradigm that is built on our life experiences, which include our racial and ethnic identity, economic status, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, family composition, nationality, citizenship status, professional and educational background, abilities, and level of health. While it is not possible for us to break out of our paradigm, shared spiritual practices may lead to relationships of trust and empathy that allow for responsible dialogue. In Taking on Practical Theology: The Idolization of Context and the Hope of Community, Dr. Courtney Goto, Associate Professor of Religious Education and Co-Director of the Center for Practical Theology, describes a critical intersubjective approach that enables researchers and members of faith communities to collaborate as they “co-construct knowledge of the faith community,” knowledge that emerges creatively in the space between researcher and collaborator(s). (Goto, 97) Attention to one’s paradigm, with particular focus on the limitations and blind spots created by one’s privilege within the paradigm, are indispensable for this approach. Professor Goto also models the effectiveness of building community through practices in the classroom in collaboration with Chris Schlauch, Associate Professor of Counseling Psychology and Religion and Psychology of Religion. I was privileged to take the course they co-teach, which embraces empathy as a strategy for relating across “paradigms of racism.”

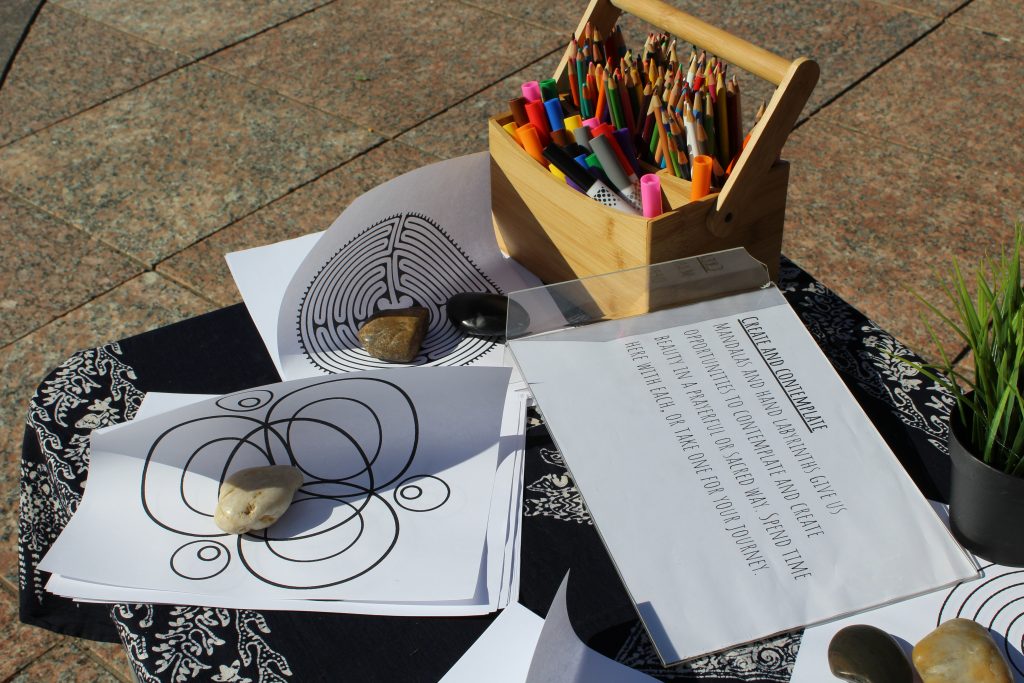

In like manner, my experience with Spiritual Companioning Groups has revealed to me how nurturing a community can help students to be active participants in their own learning and that of their classmates as we co-construct the learning environment. At least once per semester, each student is encouraged to lead spiritual practices that have been meaningful to them throughout their life. They are also invited to share a “lifemap” that includes significant experiences that have shaped their spiritual development. Other students are then encouraged to share words of appreciation and to ask clarifying questions about the stories in order to deepen their insight about the constituting experiences of their peers. In witnessing the students’ final presentations, in which they share their perspectives on “spirituality” or “companioning,” I have been pleased to catch glimpses of the creative, dynamic, and intersubjective processes that bring about profound, integral learning in only 75 minutes a week for a semester.

The benefits of my appointment as a Spiritual Companioning Group facilitator come into particular focus when considering the realities of PhD work during the COVID-19 pandemic. At this stage of training, it is not unusual for a PhD student to become absorbed in our discipline and to anxiously strive to define our research focus; asserting oneself in the academy – the “paradigm” – necessarily involves immersion in highly specialized bodies of literature and theoretical frameworks. This deep absorption in our chosen areas of research can become particularly disengaged from any sphere of praxis as we are doing our work in greater isolation from faculty and peers than in pre-pandemic times. It is unreasonable to expect that we might be able to reproduce online the kind of dialectical learning we might do through casual interactions on campus, at conferences, or in faith communities. Other teaching fellowship opportunities, which might otherwise allow for more implicit gleanings toward pedagogy for practical wisdom, can easily become quite task oriented in the absence of the embodied community in a physical classroom. The intentional focus on spiritual practices that cultivate community and engage the senses throughout my time as a Spiritual Companioning Group facilitator has provided a surprising and welcome disruption from the haze of online independent research and virtual coursework. This experience has helped me to imagine the kind of interactive teaching and research that, I hope, will contribute to expanding notions of whose experiences matter in practical theology.