Faculty Feature: Michael Birenbaum Quintero

In this CFA Faculty Feature, hear from Michael Birenbaum Quintero, associate professor and chair of musicology and ethnomusicology at BU School of Music.

Studying Black cultural politics in Latin America, Quintero’s work in Colombia examines the place of music in both the Afro-Colombian social movement and the cultural policy of the state under neoliberal multiculturalism. Beyond academia, Quintero has directed a grassroots Afro-Colombian community music archive with the grassroots research collective SINCh in Quibdó (Chocó) and has been featured on NPR.

In the interview with Quintero, the award-winning ethnomusicologist goes back in time, reminiscing on how he found his love for ethnomusicology. He also shares what makes BU’s Ph.D. in musicology and ethnomusicology unique, what opportunities are available for students in the program, and how the musicology and ethnomusicology department at BU supports students in their journey.

Q&A

AN INTERVIEW WITH MICHAEL BIRENBAUM QUINTERO

CFA: How would you describe musicology and ethnomusicology?

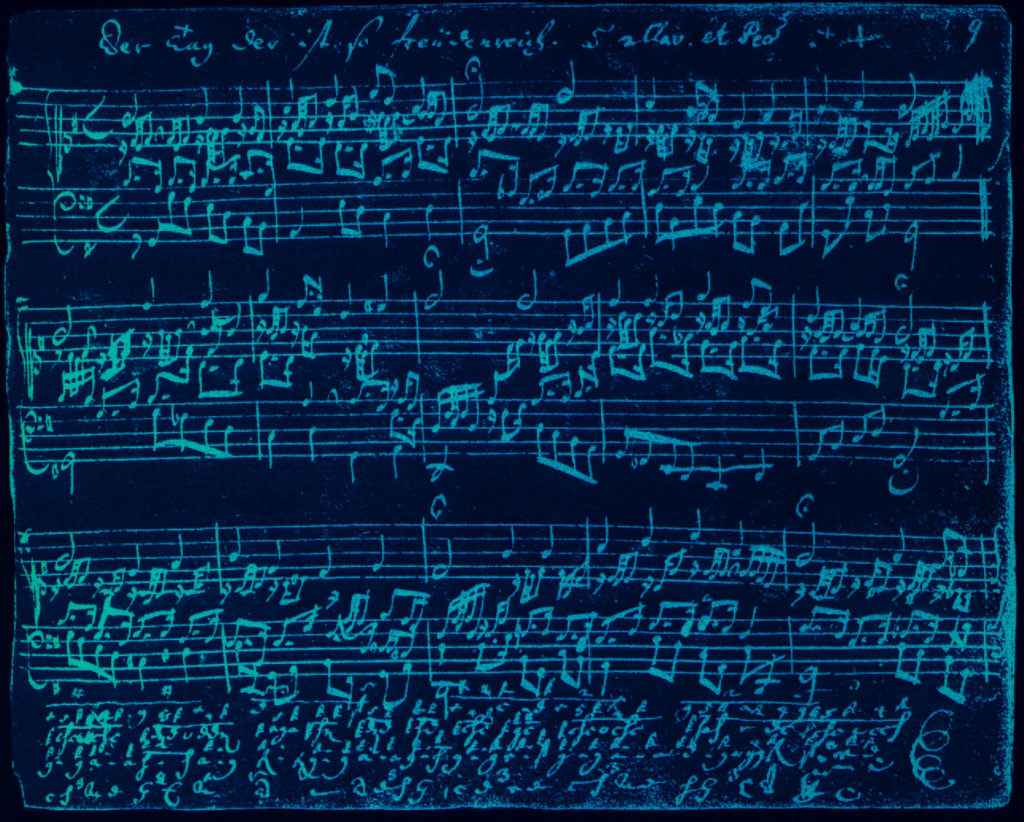

Quintero: Musicology and ethnomusicology are the study of how music works and what it does in the world. Musicology asks questions like, what are the creative processes that musicians use to do their work? What does music do in society? In what ways do artistic movements influence each other?

Musicology and ethnomusicology are sometimes spoken about as distinct sub-disciplines in which historical musicology is usually understood as the study of Western European classical music from the past and ethnomusicology is understood as the study of non-Western music in the present.

But one of the things that distinguishes our department is that we’re interested in breaking down the barriers between musicology and ethnomusicology. We’re very interested in historical research on music outside and inside of the West. We’re interested in classical music as a living practice and a historical legacy. We think about, theorize about, and collaborate with living classical musicians and audiences and non-western musicians and communities. This is an important aspect of the identity of the department.

CFA: There is no way or reason to separate the history of music from history itself?

Quintero: Absolutely right, especially if we think of music in a historical context that includes political movements, social realities, technologies, and economic structures. Music is wrapped up in all of those things. In the most basic sense, we explore what music does in the world, that is, how people think about and act on the world, through music, and how particular historical conditions influence musical creation.

CFA: When and how did you know you’d become an ethnomusicologist?

Quintero: I decided I wanted to attend graduate school for ethnomusicology because I am Colombian-American and I was very interested in Colombian music and the politics, especially the racial politics of Colombian music. Ethnomusicology gave me a set of possibilities for thinking about the relationship between society, culture, politics, and music in Colombia. That’s how it all started.

CFA: What makes the BU program in musicology and ethnomusicology distinct?

Quintero: The most important and distinctive part of this department is the faculty and graduate students that are carrying out research and teaching and taking classes here. These are the people that make this department an innovative, dynamic, engaged, and diverse (in our thinking and in many other ways) place to engage in music scholarship.

As I mentioned before, we are committed to breaking down the barriers between historical musicology and ethnomusicology. Many of us are also performers. All of the graduate students that come into the program (M.A. and Ph.D.) — whether they are musicologists or ethnomusicologists — take the same proseminar in musicology and ethnomusicology. We want them to understand the relationship between the various sub-disciplines as well as the intellectual genealogy that produced them.

Above all, we want students to have access to all the methods and theories that can be brought to bear in the study of music. We don’t want them to leave here prepared to study only western music or only the music of living performers. They should be able to study any of it. My field is Afro-Colombian music. I did my research with living musicians in Colombia. I worked with the musicians there, traveled around with them, saw their musical rituals, and was part of a large music festival. But in order to understand what I was seeing, I needed to do historical research as well. My book, which focuses on the 21st century has a chapter on the 18th century. Once you go back that far in Latin American music, it necessarily overlaps with the music of Spain. I regretted not being trained in historical methods which would have been helpful in bringing together what happened in the 18th century with what I was seeing in the 21st century.

We want our historical musicologists to know about the relationship between music and culture. Likewise, our ethnomusicologists need an understanding of history and to have skills in historical methods to design their research. Our graduates are not hampered by artificial discipline divides but are pushed forward in their scholarly inquiry wherever it takes them.

Like most schools, we offer a Ph.D. in musicology or ethnomusicology. But we also offer a Ph.D. in musicology and ethnomusicology. We have students doing very interesting work in that vein. To give you just one example, we have a student who is writing on the relationship between African and European music. His dissertation begins in the 15th century but he also did fieldwork in recording studios in Lagos, Nigeria, to examine what is happening now.

CFA: We read that you went to Colombia on a research trip, but were sidetracked because you fell in love with the music of the Pacific coast.

Quintero: I didn’t know if I was going to get into graduate school. After I applied and I was waiting to hear back, I got a job teaching English in Japan, as my Plan B. On my way there, I stopped at a friend’s house in San Francisco where I went to a music store and found some CDs to take to Japan. I played the CD in my little apartment in Osaka. The music I heard absolutely changed my life. It was so unfamiliar but I instantly fell in love with it. I had many questions. My original plan was to study the music of the Caribbean coast of Colombia but after that experience, I knew I had to switch to the Pacific Coast, although I’ve written about both.

CFA: What’s the name of the music and what makes it different from the Atlantic coast Colombian music?

Quintero: It’s called currulao. When we think about Afro-American or Afro-Caribbean music, there’s a certain kind of rhythm that is very familiar because it permeates popular culture. It’s usually in a 4/4 rhythm. But currulao is very different. It’s in a 6/8 or 12/8 rhythm. So, rhythmically, it’s much more slippery, harder for us to grasp. It uses an instrument that isn’t heard in much other Black music in the Western Hemisphere, which is marimba, akin to a wooden xylophone that has a mysterious, simmering sound. I found this music very compelling but I couldn’t figure out how it worked. I couldn’t decide when I was supposed to tap my foot. I didn’t know anything about the people who made it or where it came from. I am Colombian but I had never heard this music before.

CFA: Are there parallels between the Black Colombian experience and the Black American experience?

Quintero: There is both in the United States, Colombia, and throughout the Western Hemisphere, ongoing economic exploitation, social marginalization, and dehumanization of Black people. But it manifested itself in different ways. Obviously, people were enslaved in the United States and in Colombia. But I find the differences in these populations very interesting.

Here in the U.S., Blackness is very present. Even for people who are super racist, there is an understanding here that Blackness exists and of what it is. In the western Pacific region of Colombia, Black people retreated into the rainforest. Before and during slavery, they became essentially a fugitive population, marooned in the forest. Here in the U.S., we had enslaved people who escaped and were called “fugitive slaves.” But in Colombia, an entire society melted into the rainforest and stayed as far away as they could from the rest of society. So, instead of the hypervisibility experienced by Black people in the United States, which has engendered so much ire and hatred, in Colombia, Black people experience invisibility. In this way, white supremacy manifested itself differently in Colombia.

Claims are sometimes made by Colombians that there aren’t really Black people in Colombia, or if there are, they are fine, because Colombia, as a mixed-race society, is not really racist. Both experiences of Blackness share dehumanization but the form of that dehumanization is quite different since one is based on invisibility and the other, on hypervisibility.

CFA: Going back to the Ph.D. program, what do you look for in an applicant?

Quintero: We’re looking for three things. First, we’re looking for interesting, innovative thinkers about music. We want people who have something to say about music and are asking interesting questions about music, of music, or through music. Second, we’re looking for people who are engaged with the world. We’d like them to be interested in music in ways that are not only about music. We want people who think about music in ways that tell us about history, society, culture, and creative processes. We want them to raise philosophical questions about aesthetics. We want music and the rest of the world to be in a constant feedback loop in their minds.

Finally, we are interested in people who have a sense of some of the questions that have historically been asked about music. For our Ph.D. program, since it is so selective, we look at their writing and bibliographies very closely. They need to have the writing chops to do a Ph.D. but also, they need to have the reading chops. There is so much reading that is required of a Ph.D.-level student. We’re not expecting fully formed scholars but they need to be passionately engaged in music and able to express themselves in writing about it.

CFA: Why should a graduate student choose BU over another program in New York, Chicago, or Los Angeles?

Quintero: I think that our location in Boston is an interesting one. Some of Boston’s characteristics can be really useful to people studying particular things. One example is early music. For early music, Boston is an absolute hub, a very important place. The city’s orchestra, the Boston Symphony (BSO), has a central role in the city’s cultural scene, as does classical music, generally. The BU School of Music has a relationship with the BSO, many of its members teach here.

For ethnomusicologists, the Boston area has a number of ethnic communities in which graduate students can work. We have Greeks, Armenians, and people from all over the Caribbean and Latin America here. Nearby, the city of Lowell has one of the largest Cambodian communities outside of Cambodia. We also have a lot of Cape Verdeans here. If you’re interested in these communities, in their repertoires and histories, this is the place for you.

Above all, the faculty at BU is what makes the department so attractive to our students. There’s nothing quite like this department regarding how it approaches musicology and ethnomusicology. The question of historical ethnomusicology and what’s being called “global music history” on the musicology side, is something we’ve thought about a lot. Students can study with a leading scholar of the Renaissance lute who also studies the music of Colonial India and writes about the Rolling Stones. Or, they can work with one of the top experts on the Japanese musical avant-garde.

Another great opportunity happens when our Ph.D. students take qualifying exams. To prepare for them, they take directed studies working one-on-one with a faculty member. They get the opportunity to work with a world-renowned authority in an area of interest. I would add that students should not be too concerned about working with someone who shares the same interests they do. What you want is to work with someone who will give you the theoretical tools that you can use for any future project or interest. Your interests will evolve but you will always have the tools you need. So, we can offer students a really big tool kit. There’s a special mix of people here. We’re also a sociable and warm department and we want our students to do well.

CFA: Can you talk about some of the things current graduate students are doing?

Quintero: Yes, the best way to know what our department is about is to look at what our current graduate students are doing. Our master’s students are going on to prestigious Ph.D. programs. Our Ph.D. students are getting jobs. They are doing amazing things. We have students studying opera in South Africa. We have students who have gotten grants to study music in Senegal, Japan, Cambodia, and Belgium. Our students present at international conferences. Some of our students are on tour in Europe now singing early music from original notation. This is all right now – at this moment in time.

CFA: Anything else you’d like to share?

Quintero: It occurred to me this past fall as I was teaching the foundation course in ethnomusicology that it had been 20 years since I took the very same course in my first year in graduate school. Back then, I was apprehensive and felt out of place in the classroom. I’d been out of school for a while.

Looking back, I know now that if you trust the process of graduate education, and your professors and the staff and fellow students have your back, you will accomplish great things. So my goal as chair is to make sure that we have a department that has our students’ backs in that way. We want students to know that we are very aware of what goes into making the decision to attend a graduate program. We understand their concerns about the job market. We know that they might ask themselves why they should make this commitment during this turbulent moment in history. We respond to those concerns by working hard to give them the tools they will need to achieve their goals.

“One of the things that distinguishes our department is that we’re interested in breaking down the barriers between musicology and ethnomusicology.”

This Series

Also in

Faculty Features

-

March 29, 2023

Faculty Feature: Rébecca Bourgault

-

November 8, 2022

Faculty Feature: Kelly Bylica

-

November 1, 2022

Faculty Feature: Felice Amato

Learn more about BU’s Musicology and Ethnomusicology programs

Discover opportunities, read about additional faculty members, and explore what current musicology and ethnomusicology graduate students are up to.