news

Painting, Photography, and Radical Depictions of Gender: Franz Gertsch and Lissa Rivera

In representations of gender in art, storytelling operates on a political level by either affirming or subverting normative tropes. The artist’s power to control visibility, to selectively reveal or hide, becomes a political gesture. This paper examines the radical potential of photography and Photorealist painting within this sphere. It applies a case-study approach to read Swiss painter Franz Gertsch’s late-1970s paintings against American photographer Lissa Rivera’s ongoing photographic series Beautiful Boy. I argue that for both Gertsch and Rivera, pushing at established codes of social legitimacy and concepts of truth is an emancipatory project that challenges dominant power relations in art and society. In disrupting the dominant status quo by embracing difference as a form of political resistance, both artists construct alternative realities, imagining new worlds through art.

Photography’s ability to trouble the binary between fact and fiction can be deployed as a radical tactic for subverting rigid constructions of gender. Working collaboratively with their respective subjects, Gertsch and Rivera deploy the narrative shorthand of a portrait and the indexical associations of photography to explore the relationship between reality and fantasy. In her book Self/Image, art historian and theorist Amelia Jones writes, “the tension earmarked by aesthetics between subjectivity and objectivity is…at the core of how humans exist in the world.”[1] While many artists obscure or avoid this disjuncture, Rivera and Gertsch produce work which is consistent with what Jones categorizes as “retain[ing] rather that attempting to resolve or disavow this tension between the subjective and objective world.”[2] Invoking critic Roland Barthes, Jones notes “that representation can only deliver what we think we (want to) know about the other, who is never real but always (somewhere) Real.”[3] When it comes to cultural paradigms such as heteronormative gender categories, art can reveal the tenuous relationship between these social constructions: subject, object, and real. Making these constructions visible, Rivera’s and Gertsch’s works depict people performing a compendium of possible selves embedded in the medium.

Known for her bold colors and opulent compositions, Lissa Rivera mines the history of art and the historical conventions of painting through photography. In the series Beautiful Boy, Rivera works with her genderqueer collaborator and partner, BJ Lillis, to explore representations of the body through references to the aesthetics of classical paintings, fashion photography, and avant-garde cinema. Although conceived as a series, each composition stands alone, presenting an independent narrative. Although Lillis appears in each photograph, he performs a different role in each: a bold model, staring down the viewer; a fashionable urbanite; a downcast figure upon a bed. In aggregate, the multiplicity of images represents a variety of gender expressions of one body. They show that the self is never static, but rather, context-specific, fluid, and unconstrained.

A political project underlies the arguably seductive visual appeal of these saturated colors and sumptuously detailed backgrounds. In an interview for this essay, Lillis described his perception of viewers’ responses to the photographs. He noted:

They like them already before they have time to think about their own politics or how they might feel about what we’re doing on the political level. By the time they even register my genderqueer-ness, they already like the photos because of the colors and the way that they’re composed.[4]

By putting into circulation easily-appealing photographs of an individual whose marginalized identity is not immediately apprehensible, Rivera and Lillis play with the viewers’ expectations of the image, while simultaneously commenting on the political and aesthetic possibilities of the photographic medium. For Rivera, the process of their photographs’ integration into mass visual culture through the internet, print publications, and exhibition spaces is political because it serves to balance pervasive depictions of bodies that conform to rigid gender-norms.[5] When interviewed for this essay, Rivera also noted that, “BJ is able to express this Baroque version of femininity that I could never express myself. In a way, he’s dressing up as my fantasy self.”[6] Thus, Rivera and Lillis explore gender as a construct, using staged performance to work through various depictions of both their gender expressions.

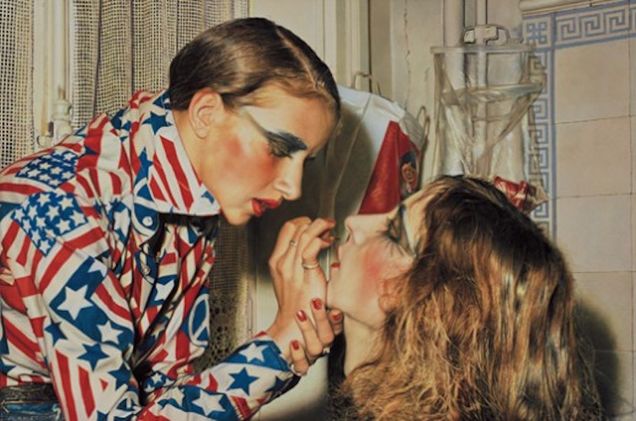

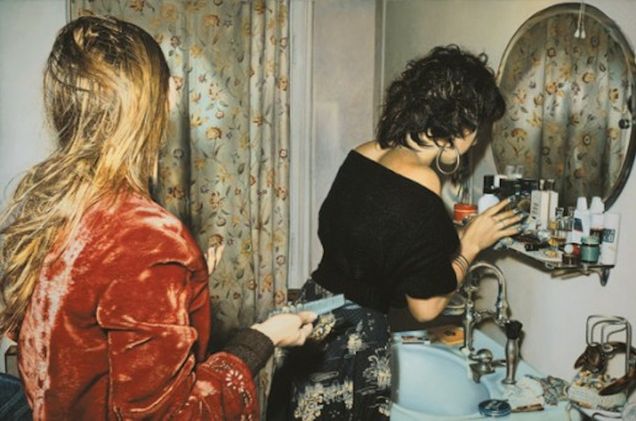

Gertsch’s large format Photorealist paintings from the 1970s explore the potential for remediation in photography and painting through the depictions of his frequent portrait subject, friend, and fellow artist, Luciano Castelli. His three-part sequence of paintings, At Luciano’s House (1973), Barbara and Gaby (1974), and Marina Makes Up Luciano (1975), is especially evocative. Derived from three photographs taken on the same day, the three paintings depict a group of the artist’s close friends, named in Gertsch’s titles. By selecting three distinct moments from the same evening, the artist invites the viewer to imagine a narrative, leaving open the possibility of interpreting these compositions along different story arcs.

Unlike Rivera, who only uses natural light and long exposures, Gertsch utilized a bright flash to photograph these indoor situations. The resultant stark contrast and sharply outlined, saturated silhouettes of the source photographs heightens the desired hyper-real style of Gertsch’s paintings. By mimicking the effects of a short focal length and close cropping, these paintings reproduce the formal characteristics of voyeuristic and unposed snapshot color photographs. Yet, due to their large size and Gertsch’s meticulous attention to detail, the paintings were completed over a three-year period.[7] This paradoxical elongation of time—from a momentary flash to a prolonged painting project—lends tension to the relationship between the photographic and painterly in Gertsch’s Photorealist paintings.

Like Rivera’s portraits of Lillis, these group portraits by Gertsch also deeply engage with the politics of gender. The painting At Luciano’s House shows the group in Castelli’s home as they dress for a party. Marina (as identified in another painting) is caught in motion as she either puts on or removes a jacket, her hands clutching the lapels while she looks at something outside the frame. The next painting, Barbara and Gaby, follows an implied course of events that evening as the friends apply makeup and style their hair using an abundance of toiletries. In this painting, the two figures stand with their heads turned toward the mirror, concealing their faces. They are nevertheless coded as female bodies, their hairstyles, clothing, and grooming accessories functioning as the culturally-constructed identifiers of femininity.

In the third and final painting of the sequence, Marina Makes Up Luciano, Gertsch complicates this normative portrayal of gender expression. Marina is poised above Castelli, the closely cropped composition accentuating the action of the painting: her finger smudging the crimson lipstick on his lips. Gertsch emphasizes the frozen motion of her hand by centering the two figures within the close framing of the image. Castelli’s face is turned upwards toward Marina. She stabilize one of her hands with the other, bracing it against his chin. With their makeup applied identically—the heavy eye shadow, elongated black eyeliner, and radiant red blush—they seem like reflections of each other. The overall mirroring effect of their makeup, tandem poses, and matching facial expressions produces an uncanny doubling effect. Paradoxically, they are at once similar yet distinct. The assertion within the title—that Marina “makes up” Luciano—suggests that she does more than apply makeup to his face. In a strongly evocative way, the title implies that she somehow “makes up” Luciano in the sense of conjuring a fabrication, thus hinting at and blurring the binary distinction between fiction and reality in the painting. The ambiguous and constitutive nature of their gender identities is part of the point.

When viewed together, the works of Rivera and Gertsch prompt us to consider gender and identity as boundless constructs. Comparing Gertsch’s Marina Makes Up Luciano with Rivera’s Boudoir (2015), we can see how both artists embrace the interplay between truth and performativity. Each composition purports to capture a moment of action, frozen in time, as the subject is transformed through the gesture of the hand within the frame. In Boudoir, Rivera’s gloved hand reaches into the space of the photograph to smooth Lillis’s hair with a brush. The artist’s involvement reveals the carefully-staged nature of the work. The tension between artifice and performativity is embraced, not resolved or concealed. This interplay of subjectivities and mediums that occurs in both Marina Makes Up Luciano and Boudoir is reminiscent of what Jones terms “the contingency and embeddedness of the self on/in the other.”[8] Both works show how gender and identity are not individually constituted, but socially constructed. Gertsch and Rivera offer us a way of conceptualizing gender through the complex relationship between photography, painting, and performativity.

Maria V. Garth

____________________

[1] Amelia Jones, Self/Image: Technology, Representation, and the Contemporary Subject (London: Routledge, 2006), 10.

[2] Ibid., 10-11.

[3] Ibid., 248. See also Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, translated by Richard Howard (New York: Hill & Wang, 1981).

[4] B. J. Lillis, interview with the author, February 10, 2019.

[5] Lissa Rivera, interview with the author, February 10, 2019.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ulrich Loock, “Group Portraits from the Early Seventies,” in Franz Gertsch: Retrospective, edited by Franz Gertsch, Reinhard Spieler, and Samuel Vitali (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2006), 113.

[8] Amelia Jones, Self/Image, 10.

Botticelli: Heroines + Heroes

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

February 14 - May 19, 2019

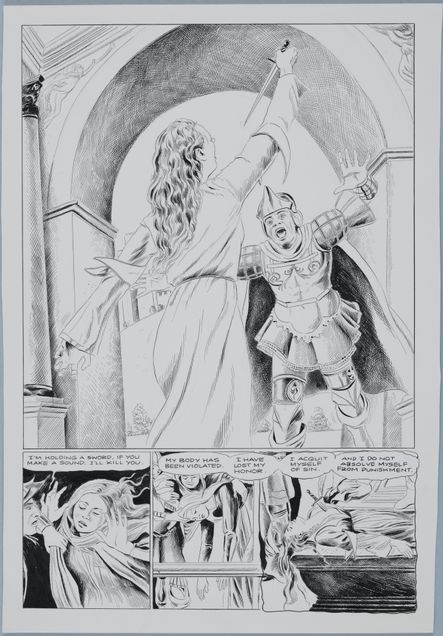

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum’s exhibition, Botticelli: Heroines + Heroes, brings together paintings by the Renaissance master Sandro Botticelli (c. 1445-1510), showing how Roman and early Christian figures were depicted as role models in his own time. Paintings and drawings created by the artist in the last decade of his life appear alongside drawings by the graphic novelist Karl Stevens that provide contemporary commentary on the paintings’ subjects. Displayed against fuchsia and grey walls, the Renaissance artworks are contrasted in both style and color to Stevens’ black and white graphics.

The highlight of the exhibition is the reunion of two paintings: the Gardner Museum’s own The Story of Lucretia (Fig. 1) and The Story of Virginia (Fig. 2), on loan from the Accademia Carrara, Bergamo. The first gallery of the exhibition is dedicated to the acquisition of Lucretia, carried out by Isabella Stewart Gardner herself in 1894 and includes early museum records and correspondences regarding the purchase.[1] A twelve-panel comic by Stevens (Fig. 3) re-envisions the narrative of the acquisition, providing context and humor through its dramatic dialogue between Gardner and art historian Bernard Berenson.

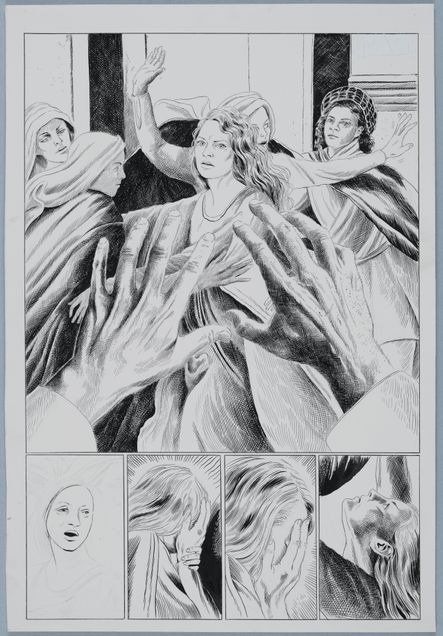

The second gallery has an octagonal structure at its center, recalling the iconic Baptistery of St. Giovanni in Florence, the city where Lucretia and Virginia probably originated.[2] Within the geometric space, the two works are paired side-by-side, facing three paintings with scenes from the life of Saint Zenobius. One of the exhibition’s greatest strengths is its treatment of the theme of male aggression and violence against women, a subject with poignant relevance today. Lucretia and Virginia are Roman heroines celebrated for their mortal sacrifices that preserved their female virtue and familial honor.[3] Botticelli’s paintings depict traumatic scenes leading up to the women’s deaths by suicide and murder. Steven’s drawings augment these themes by providing a sense of female perspective and anxiety, captured, for example, in the man lunging towards Lucretia and in the large and powerful hands reaching for Virginia (Figs. 4-5). However, the thematic impact of heroinism in the face of adversity is downplayed by the display of Lucretia and Virginia directly across from images of Saint Zenobius. Paired with Stevens’ drawings of Florentine landmarks that lack critical commentary on the Zenobius imagery, paintings of the male saint celebrate his life and miracles in comparison to the women’s martyrdoms. An opportunity to emphasize the stark visual differences of male and female heroisms seems missed.

Botticelli: Heroines + Heroes asks visitors to rethink the meanings of Botticelli’s paintings, whether as parts of a museum collection or as commentary on changing (or unchanging) attitudes towards the treatment of women. Despite its somewhat disconnected themes—heroism, the museum’s Botticelli acquisition, and the violent experiences of women—the combination of artworks alongside Stevens’ drawings provides visitors with a visual array of Botticelli’s later works and juxtaposes issues surrounding women's experiences today with images from the past.

Jillianne Laceste

____________________

[1] Nathaniel Silver, ed. Botticelli: Heroines + Heroes (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum; London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2019), 101.

[2] The two paintings were “probably commissioned by or for Giovanni di Guidantonio Vespucci (1476-1534) on the occasion of his wedding to Namicina di Benedetto di Tanai de’ Nerli, Palazzo Vespucci, Florence.” Botticelli: Heroines + Heroes, 101.

[3] Botticelli: Heroines + Heroes, 96.

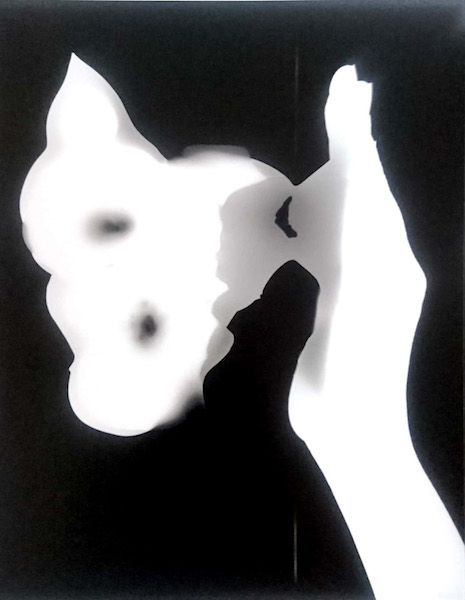

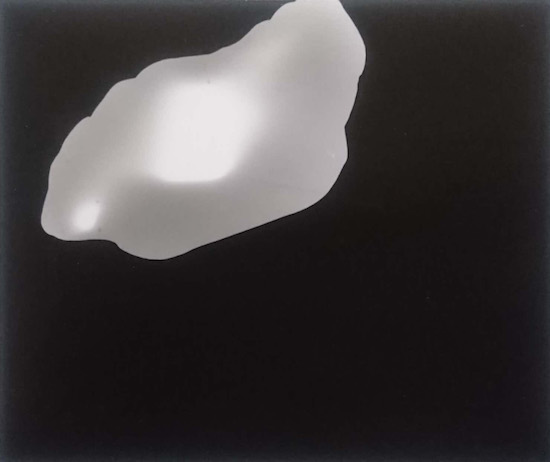

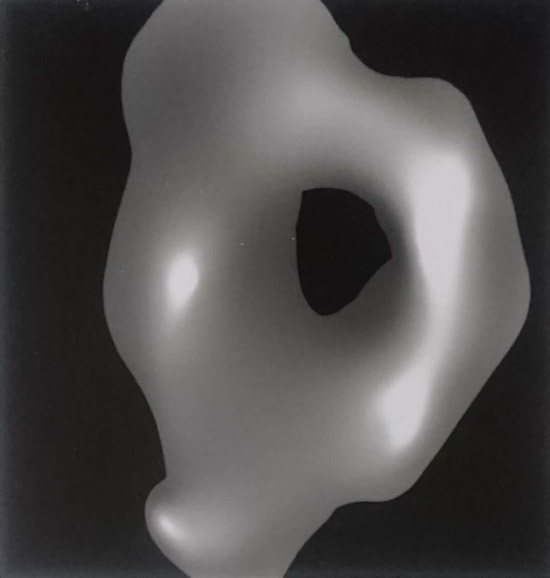

Processes as Objects

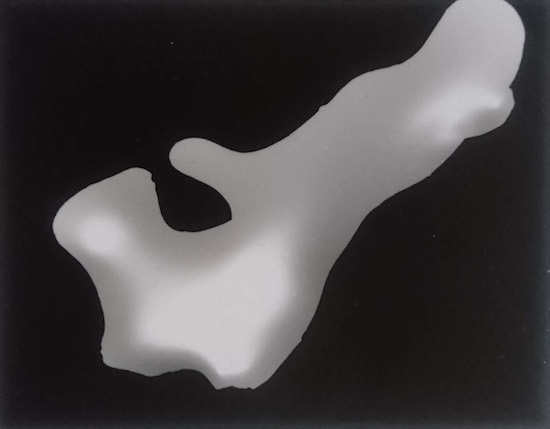

My printmaking practice explores the “objectness”[1] of stones, pebbles, and cobbles. Informed by Heiddegerian Object Oriented Ontology, my work expands how we define objects. It presents them as things with histories, “irreducible in both directions: an object is more than its pieces and less than its effects.”[2] In the series Souls and Eclipse I complicate and question the boundaries of objects. Using photograms, a photographic process that results in a loss of visual information, the objects in my series are presented in unusual ways that work to defamiliarize viewers and invite them to focus on the unknown or overlooked qualities and aspects of the object.

In the series Souls, I display stones in a way that reinforces their “objectness” by hinting at an inner depth – the photogram technique seemingly removes their surface, which gives viewers the illusion of looking inside them. The visual uncertainties caused by tonal differences question the objects’ material qualities and boundaries. In the Eclipse series, I visualize how an event can also be seen as an object through employing “flat” imaging techniques. Again, using the photogram technique, which allows me to render a four-dimensional event into a two-dimensional image, I am able to hint at the eidetic properties of objects. Such events cannot be directly recorded in Souls, but the shapes in both series are still similar, highlighting that the holes, surfaces and connections we see are not mere topography – they are the marks of events in the objects’ (hi)stories.

Rebeka Sara Szigethy

Armenia!

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

September 22 - January 13, 2019

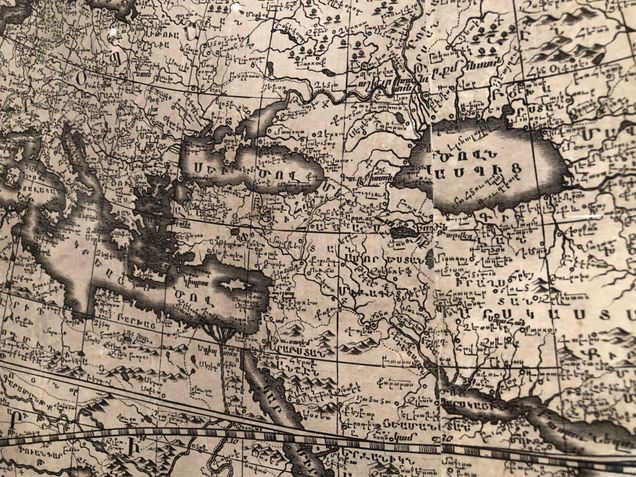

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition is the first significant attempt in the United States to explore the legacy of Armenian artistic and cultural productions.[1] The exhibition includes works from between the fourth and seventeenth centuries, presenting a complex history that reaches beyond the rigid categorizations of medieval Christian studies. Helen C. Evans, the exhibition’s curator and a specialist of Byzantine art at the MET, has brought together 140 rare objects, including church models, cross stones (khachkars), illuminated manuscripts, liturgical furnishings, metalwork, and textiles from several national and international public and private collections.[2] These distinctive works of art and culture demonstrate how Armenians interacted with the world around them while simultaneously maintaining their own unique identity in a multi-cultural, multi-ethnic region (Fig. 1).

In Armenia!, visitors are immersed within the vigorous dynamics of fourteen centuries of Armenian art and architecture as they walk through six different galleries. These separate sections make it clear that the standard approach of looking at Armenian art only through the lens of Christian art has shortchanged this rich culture. The galleries begin with Armenia’s conversion from polytheism to Christianity, and then continue to present sample objects that highlight art and architecture from the Armenian Kingdoms of Bagratid, Artsruni, and Cilicia. The final gallery explores works of Armenian craftsmen during the Ottoman and Safavid Empires.

The four-sided stela that commemorates Armenia’s Christianity acts as an entry point to the exhibition (Fig. 2). When St. Gregory the Illuminator converted the early-fourth-century CE King Tiridates the Great to Christianity, Armenia became the first region to formally adopt Christianity and to abandon polytheism. Medieval ceramics from Dvin illuminate Armenians’ active trading relationships with other regions. A glazed bowl dated to the eleventh century depicting an eagle — a heraldic bird — is one of the luxury lusterware examples on display (Fig. 3). Imported from Iran and Syria, lusterware was considered a luxury item and was widely used by Armenian elites as tableware between the ninth and thirteenth centuries.

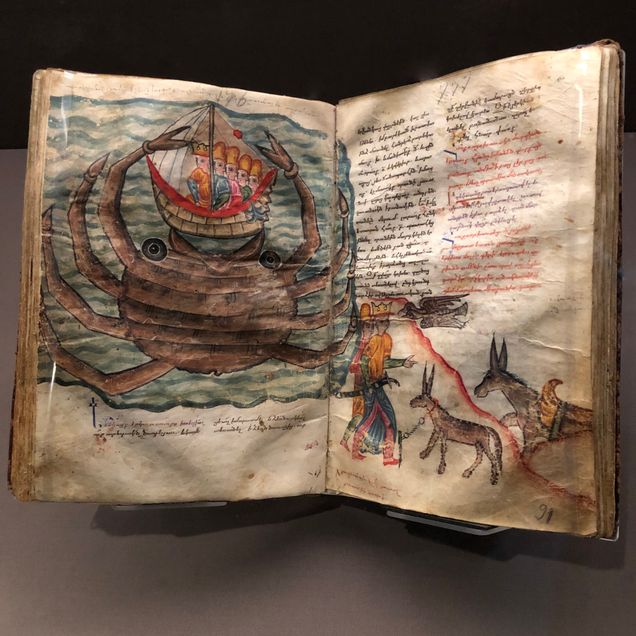

Fantastic animals – fictional hybrid creatures that represent magic, power and other-worldly mysticism – are widely depicted in Armenian architecture. The thirteenth century bas-relief of a sphinx from the monastery of Yovhannavank is just one example of their common depiction in Armenian architecture (Fig. 4). Similar fantastic animals are encountered in Byzantine, Georgian, Mongol, and Seljuk architecture of the medieval period. In terms of literature, the Alexander Romance– the body of legends about the career of Alexander the Great – was popular among the Armenians. A folio from a sixteenth-century manuscript of the Greek Alexander Romance,” illuminated by Bishop Zak’ariay of Gnunik’, shows an episode where a giant crab swallows Alexander’s ship, and then afterwards two donkeys lead and accompany him through the land (Fig. 5).

The cultural production of Armenian art and architecture requires in-depth scholarly analysis and curatorial attention. With this in mind, the MET’s Armenia! exhibition offers a good starting point for better understanding the distinctive nature of Armenia’s objects and monuments and the fourteen centuries of its cultural interactions and trade relationships with other populations across Anatolia, Iran, the Mediterranean, and the South Caucasus.[3]

Bihter Esener

____________________

[1] The author would like to thank the Freer Fellowship of the History of Art Department at the University of Michigan for providing the opportunity to visit this exhibition. The author also thanks Rachel Cochran and Emerson Floyd.

[2] For more information about the exhibition see Helen C. Evans, ed., Armenia: Art, Religion, and Trade in the Middle Ages (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018).

[3] For a recent critical survey of ancient, medieval, and early modern periods of Armenian art see Christina Maranci, The Art of Armenia: An Introduction (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Editors’ Introduction

This issue of SEQUITUR looks to boundaries, both physical and conceptual, to explore what it means to “[cross] the line.” Borders, as lines of containment or exclusion, intrinsically bring dichotomies to the forefront; their “crossing” is often viewed as an act of transgression. The contributors for this issue explore the places where boundaries exist, the dualistic opposition their existence establishes, and how the “crossing [of these] lines” can both be an act of deviancy and conjure new meanings.

In the feature essay, Evan Fiveash Smith explores the politics of transgender representation seen in Greer Lankton’s relationship to her semi-autobiographical, ever-changing dolls. The dolls and mannequins that serve as the nexus of Lankton’s work inhabit a nebulous space, between living subject and inanimate object. Between the restrictive, traditional binaries of gender, Lankton and her dolls provoke new ways of considering subjectivity.

Rebeka Sara Szigethy’s visual essay questions how we define objects. Using photograms of stones, she dissolves the boundaries that surround the concept of “objectness.” In the process of transforming a real-world object into a two-dimensional image, Szigethy questions how objects exist. Can they be read as subjects? And, can different strategies of visualization, such as the tactility of the photogram, help change our relationship to these objects?

The interview between Jonathas de Andradeand Catarina de Araújo discusses how the Brazilian artist’s work in installation, photography, and video crosses the borders of gender, class, race, and nation-state. The artist’s work asks the viewer to situate themselves within the dialogue of “us” and the “other.”

Both of the exhibition reviews highlight the reunion of artwork and objects from across geographical boundaries. Jillianne Laceste explores the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum’s exhibition, Botticelli: Heroines + Heroes, the centerpiece of which is the reunion of the master’s sister paintings The Story of Lucretia and The Story of Virginia. Bihter Esener provides a detailed overview of the Metropoitan Museum of Art’s Armenia! exhibition, which brought together objects from collections around the world in the first major exhibition on medieval Armenian art and culture in the United States.

The two book reviews, Sara Stepp’s on The Politics of Painting: Fascism and Japanese Art During the Second World War by Asato Ikeda and Amber Harper’s on L’Origine du monde: Vie du modèle by Claude Schopp, focus on publications that question traditional scholarly arguments by reframing the contexts of artistic production and display.

Finally, Rachel Hofer, co-coordinator with Kiernan Acquisto, reflects on Boston University’s 35th annual Graduate Symposium in the History of Art & Architecture, which was held at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston on March 2, 2019. Titled “Frontier: Exploring Boundaries in the History of Art and Architecture,” the symposium served as inspiration for this issue’s theme. Dr. Ila Sheren, Assistant Professor of Art History and Archaeology at Washington University in St. Louis, gave the keynote address, which centered around some of India’s major waterways and the intersection of religious practices and environmental pollution. Graduate student papers focused on the transgressive and restrictive nature of borders.

This issue’s contents ask our readers to question the boundaries in their own lives, to challenge established frameworks and conventional methodologies. What can it mean to establish limits and what can be enabled by “crossing the line”?

We would like to offer a special thanks to our outgoing Senior Editors Kimber Chewning, Lauren Graves, and Ali Terndrup, who have not only overseen a rebranding of the journal but also continually pushed to expand its conceptual boundaries. Their insight, guidance, and collegial spirit have been defining characteristics for SEQUITUR. We hope to continue to build upon their work and are excited to see which boundaries SEQUITUR will cross next.

-Bailey Benson

Frontier: Exploring Boundaries in the History of Art and Architecture – The 35th Annual Boston University Graduate Student Symposium in the History of Art & Architecture, March 2, 2019

This event was generously sponsored by The Boston University Center for the Humanities; the Boston University Department of History of Art & Architecture; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and the Boston University Graduate Student History of Art & Architecture Association.

This year marked the 35th annual Boston University Graduate Student Symposium in the History of Art and Architecture. Taking place in the Trustees Room at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the symposium hosted six graduate student speakers who delivered papers exploring boundaries within the history of art and architecture. Frontiers conjure fraught historical moments, instances of subjugation and resistance, and thresholds charged with possibilities. The graduate student papers featured in this year’s symposium addressed questions of how frontiers, both physical and metaphorical, impact artistic production as creators engage with and negotiate boundaries.

The symposium took place on Saturday, March 2nd, and showcased six graduate student presentations divided into morning and afternoon panels. The morning session featured papers centering on the theme, “Border Crossings,” in an effort to highlight the liminal nature of many frontier spaces. All three speakers looked to frontiers as areas of mediation and collaboration. In the first paper of the day, “Liminal Objects, Liminal Spaces: Masterpieces of French Tapestry and the Shaping of Museum Practice,” Nushelle de Silva (MIT) addressed the transnational nature of museum exhibitions through a close examination of the first post-WWII major multinational exhibition: Masterpieces of French Tapestry. The 1946-1948 exhibition provided new opportunities for collaboration across institutions and national borders; and resulted in the codification of international museum lending practices by the end of the 1950s. The second speaker, Savannah Marlatt (University of British Columbia), explored issues of methodology in her paper, “Representation, Mediation, and Image: Theorizing Islamic Portraiture Beyond Methodological Boundaries.” Marlatt interrogated what constitutes a “portrait” to determine if theories developed for European renaissance portraiture can be applied to Islamic portraiture. Finally, in her paper “Speaking with the Ancestors: Death as a liminal space among the Wari,” Louise Deglin (UCLA) addressed the true final frontier: death. Through an analysis of stylized skull motifs on pottery, Deglin argued that these ceramics were used by the Wari to spread their ideology and connection to their ancestors as a way to access and maintain power throughout their empire.

While the morning session focused on the conceptual nature of borders, the afternoon session featured papers that engaged with the physical nature of borders and the frontier as a limit in a panel titled, “Border Control.” The first speaker of the afternoon session, Amy Miranda (Johns Hopkins University), destabilized the center-periphery model in the study of Roman art and architecture. In her paper, “Felt Spaces of the Porte Noire as Collective Memory Practices,” Miranda used the Porte Noire, a commemorative arch along the northern border of the Roman Empire, to demonstrate the active role of Roman provinces in community building and unification. The second presenter, Kennis Forte (Queen’s University), considered the pilgrimage sites throughout the Italian regions of Piedmont and Lombardy as a unified “spiritual border wall” in her paper, “The Sacri Monti as markers of a spiritual border in Early Modern Italy.” Forte argued that the Sacri Monti functioned as a Roman Catholic spiritual blockade against the heterodoxy of Protestant sects in Switzerland and Germany. The last graduate speaker of the day, Kelsey Petersen (Tufts University), presented the Haitian artist Jean-Ulrick Désert’s The Waters of Kiskeya/Quisqueya as an exercise in decolonization through the process of artistic counter mapping. Throughout her paper, “Interrogating Cartography: Counter-Mapping the Caribbean Archipelago,” Petersen demonstrates how Désert reclaims and reorients the Caribbean from a traditionally hegemonic European point of view.

After the six stimulating graduate presentations, the day culminated in a keynote address by Dr. Ila Sheren, Assistant Professor of Art History and Archaeology at Washington University in St. Louis. In her presentation, “Bordering on the Sacred: Visualizing the Paradox of Pollution,” Dr. Sheren addressed the confluence of religious practices and pollution in some of India’s major waterways, as well as on land. Focusing on the work of filmmakers Vibha Galhotra (Manthan, 2015) and Amar Kanwar (The Scene of the Crime, 2011), Dr. Sheren explored the impact of religious practices and the lasting effects of colonization/decolonization on India’s natural resources. Her talk raised questions about agency, exploitation, and personal versus governmental responsibility.

This year’s symposium generated fruitful conversations among the audience, graduate student presenters, and keynote speaker about the nature of the frontier and how it is represented in art and architecture. The speakers challenged what constitutes a frontier as they explored spiritual, conceptual, methodological, and national boundaries. Undoubtedly, the seven presentations gave everyone present new and exciting ways to engage with the frontier in art, architecture, and scholarship.

Rachel Hofer

Notes on Contributors

Catarina de Araújo, originally from Recife, holds a B.A. in Journalism (2006) and an M.Ed from DePaul University in Chicago (2011). After spending nearly ten years working as a visual arts educator, she is now pursuing an M.A. in Art History at Oklahoma State University. Her research focuses on Modern Brazilian photography and printmaking.

Bihter Esener is a Ph.D. candidate in History of Art at Koç University, Istanbul. She is currently a Freer Visiting Graduate Student Fellow in the Department of the History of Art at the University of Michigan. Her dissertation aims to contextualize bronze mirrors within the lives of the inhabitants of medieval Anatolia.

Amber Harper is a PhD student in Art History at Stanford University. She received an MA from Columbia University in 2015. Her current research focuses on European modernism and the historical avant-garde as well as the histories of film and modern media.

Rachel Hofer is a doctoral student at Boston University where she specializes in seventeenth-century Dutch art. Her dissertation project addresses Rembrandt within a global context. She received her M.A. in Art History from the University of Iowa and her B.A. in the History of Art & Italian Studies from the University of California, Berkeley.

Jillianne Laceste is a Ph.D. student in the Department of History of Art and Architecture at Boston University focusing on early modern Italian art. Her research interests include gender, sexuality, and identity in portraiture and images of the domestic sphere.

Evan Fiveash Smith is an MA candidate in the History of Art & Architecture program at Boston University. He recently co-curated Under a Dismal Boston Skyline at the Boston University Art Galleries.

Sara Stepp is a PhD candidate at the University of Kansas, where she studies art since 1960. Her research often focuses on memory, history, and multi-cultural interchange in contemporary art. Her dissertation examines the ways that contemporary Chinese-American artist Hung Liu’s works engage, both in subject matter and in style, with overlapping issues relating to time, place, and identity. Sara has worked, interned, and consulted at several museums and galleries. She currently serves as the curatorial intern of European and American art at the Spencer Museum of Art, and a curatorial research assistant at the National Museum of Toys and Miniatures. She also works as an instructor of art history at Baker University.

Rebeka Sara Szigethy is an MA student in Fine Art at the University for the Creative Arts in Canterbury, UK. Born in Hungary, she is currently living and working in Folkestone, UK. She holds an MA degree in Hungarian Language & Literature (Karoli Gaspar University, Budapest, Hungary) and a Foundation Degree in Printmaking (Obuda School of Art & Design, Budapest, Hungary). Her visual, scholarly and literary works have been published both in English and Hungarian. Her portfolio is available at www.works.io/rebeka-sara-szigethy.

Catarina de Araújo interviews Jonathas de Andrade

Jonathas de Andrade is a contemporary artist working in installation, photography, and video. His work embraces elements of regional specificity while invoking universal themes associated with memory, place, and the human condition. Jonathas de Andrade: One to One is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago April 13 - August 25, 2019. The following interview was conducted via e-mail and audio exchange and translated from the original Portuguese by Catarina de Araújo.

Q: Because your work is so connected to your place of birth in Northeastern Brazil, could you speak about your relationship to the region—its people, history, and landscape? More importantly, what has been the impact of these early experiences in Brazil on your work today?

I was actually born in Maceio, Alagoas, but I have been living in Recife for fifteen years. This is the place I was able to initiate my artistic career, a place that I chose to live in and have a house, a place that I love and care for. But growing up in Maceio, I think I was exposed to the complexities of Northeastern Brazilian culture: the sugar cane culture, the plantations, the elites, the poor, the class conflicts. All of these factors were conditions that I observed and felt during childhood, and that have greatly impacted me, along with all the nuances that come along with this power struggle. So, you know... as seen in projects such as Museu do Homem do Nordeste (Museum of the Man of the Northeast), O Peixe (The Fish)... the reflections of eroticism and masculinity are questions and interests that have challenged me since I was young, growing up in Maceio. [As for] Recife, I arrived in my early twenties to attend communications college after attending law school in the south, which I never finished, but I ended up immersing myself in video, cinema, and photography. All of this is a part of my journey of mixing interests with concepts and angles.

Q: This is a personal question for me because as a Recifense myself, I am wondering how you were able to distinguish yourself artistically in a city so attached to both modismos (trends) and tradition. How did you go beyond the visual norm of a region that, I dare to say, is still very much Modern, grounded in cubism, expressionism, and surrealism? Also, since your work falls so evidently outside that category, can you comment on your understanding of the visual arts scene in Recife, as it may very well diverge from my view?

To be honest, because I am not "Recifense," I think that I, in some ways, feed on this scene and the complexities and contrasts that the city brings. But I go beyond, crossing the line of thinking about identity and so forth because, to be honest, I am more interested in universal questions. I am interested in the subtlety of power and the perversions of power relationships that are acclimated into society, day-to-day. I am also interested in the inherent exchange present in power-relationships, of a hierarchy, but also through the role that eroticism plays and through what is unspoken. This is very common in Brazilian society, especially when we talk about the Northeast. So I think my work may have a Modern background, but my goal is to reach these other topics, to reach beyond.

Q: On a similar note, how do you think your work is accepted and viewed in the Northeast [of Brazil] as opposed to other regions nationally and internationally, especially in the United States? How do you feel about any differences?

So, I think that internationally the Brazilian Northeast is seen as an exotic place and so forth. But I also think that there is a certain comfort propagated by this initial appearance. The viewers relax and get the opportunity to wander through the work... [they] think about what is beyond and what is universal. For example, with Ressaca Tropical (Tropical Hangover), there is something about empathetic memory, a question about literature. There are [references to] various archives [and] historical documents, but together, they morph into fiction. This ambiguous game is interesting to me. In O Peixe (The Fish), [the work] uses a prominent ethnographic aesthetic, but in actuality, there lurks a discussion surrounding fiction and non-fiction, what is real and what is not, also about the taming of nature, about love and violence. All these themes are much more universal than their initial appearance of a specific story about a specific community in the Northeast of Brazil. So I think that this is when I enter a powerful exchange between what is universal among these relationships... so inherit of the human condition.

Q: My favorite video work of yours is O Caseiro (The Housekeeper) because I believe Brazilians urgently need to talk about Gilberto Freyre and race. [1] My experience has been that Brazilians, in general, prefer to diffuse racially charged conversations, especially among international audiences. We still tend to romanticize and use elements of racial democracy in conversations, even though we are so aware of racial disparities. Why was it important for you to create this video and what were you hoping to get out of your audience?

I would dare to say that this is changing. I think that recently, in later years, there is an empowerment movement among Brazilians of Afro-descent and mixed backgrounds. I think that now, there is an organized movement that has advanced discussion, in a sense. There is a discussion surrounding the legitimation of discourses - who can say what about what. This is very prominent in Brazil right now, but at the same time, racism has not gone away. In fact, it is much more pervasive and explicit, right? Institutionalized racism manifested by police brutality, we see it frequently. Marielle Franco for example. [Brazilian politician of Afro-descent and outspoken critic of police brutality, Franco was shot multiple times and killed in Rio de Janeiro. Two former police officers were arrested and charged with her murder earlier this year.] This very week, a family inside a car was shot eighty times, and the police said it was a mistake. It is very sad, but as I said, I think that people are talking and advancing the debate. About the video O Caseiro (The Housekeeper), it juxtaposes a film about a presumed housekeeper in the house of Gilberto Freyre, with a historical film about Freyre himself. We can see the complexity of this character that initiated a dialog and constructed ideologies of classes and race, but that himself carried aristocratic attributes – and he is portrayed like that. There are all these dynamics happening with his image and his identity in the film. It is very interesting, for example, to see that he had workers; that there is an element of servitude there. And there is also a temporal element because... I think that, during that time...[Freyre’s] introducing the house servants by name, perhaps signaling proximity, was maybe even an avant-garde gesture. Today, this would not be okay. Can you imagine yourself as a writer and an intellectual being videotaped with a servant in your house? It is interesting to me, as well, to see how expectations change over time. What is accepted and what is not. So there is a protagonist game. If Gilberto was the protagonist, after he dies, in the house, it is as if the housekeeper now becomes the protagonist. This raises, I think, interesting questions.

Q: Now turning to your exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, could you talk about Suar a Camisa (Working Up a Sweat) and another theme often present in your work: that of the common man and the common worker? Also, what other works should your Chicago audiences expect to see as part of the exhibition?

Now talking about the MCA. Yes, the exhibition consists of four projects, basically. A previous one, Suar a Camisa (Working Up a Sweat) and three other new ones. About the Suar a Camisa, you asked about the recurrence of the common man in my art or the common worker. I think this theme emerges from the very beginning, when I started to use the name of the Museu do Homem do Nordeste (Museum of the Man of the Northeast). Which is a museum that exists, in fact, created by Gilberto Freyre – but I started using [it] strictly like it is the museum of masculinity. I use the title, that is sexist and problematic and attach this thematic... I dive in, like a study about the identity of the Northeastern man – in proximity to the stereotype of this man that is rudimentary, a worker, a brute strong man, that works with force, with his arms and hands. That is very much inherent of the "macho" culture of the Northeast. But at the same time, I approach through the lens of eroticism, vanity, and sensuality and there is something disconcerting about this approximation. At the same time that you display and bend the stereotype, you also come close to it and reproduce this stereotype, in order to deconstruct. And this process involved a series of fiery procedures. So the work itself, Suar a Camisa, is a collection of sweaty shirts that were negotiated, bought, and exchanged with workers on the streets. Workers going to work or returning home from work. Through this negotiation, there is the presence of the body across these t-shirts, the presence of sweat, but also the absence of the workers and the absence of their identities there.

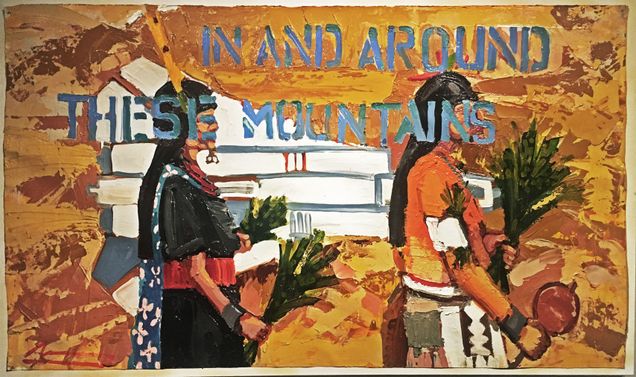

Also featured in the exhibit will be a video commissioned by the MCA, Jogos Dirigidos (Directed Games), which was filmed in a deaf community in the interior of Piaui; a real, large scale drawing, Um para Um (One to One) which provides the title to the exhibit; and a project called Fome de Resistencia - Fundamento Kayapo Menkragnoti da serie Infindavel Mapa da Fome (Hunger of Resistance - Kayapo Menkragnoti Foundations from the series Endless Hunger Map), which is composed of forty-two maps taken from the Brazilian army and marked by the hands of women from the Caiapó indigenous community.

Catarina de Araújo

Download Article

____________________

[1] Gilberto de Mello Freyre (1900–1987) was a sociologist specializing in the socioeconomic development of the multicultural and multiracial society of the Brazilian northeast.

L’Origine du monde: Vie du modèle

Claude Schopp

L'Origine du monde: Vie du modèle

Paris: Editions Phébus, 2018. 152 pp.; 8 color ills.

$14.29

978-2752911780

L’Origine du monde was completed by the French painter Gustave Courbet in 1866. The painting presents a female nude lying against a bedspread. Her thighs open toward us, her jaundiced torso entangled in a white bedsheet. The edge of the canvas cuts into her thighs, truncating her limbs so that her torso occupies the entire canvas; her head, arms, and legs lie outside the frame. This cropping brings an unequivocal focus to the central element of the composition: the woman’s unshaven pubis mons and open labia. Despite the visual candidness of the painting, very little is certain about its history. L’Origine du monde was commissioned by its original owner, the Ottoman diplomat Khalil Bey, and went missing when the collector lost his fortune. The painting resurfaced in the mid-1950s and was purchased at auction by the famous psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. From the painting’s beginnings to its current hanging in the Musée d’Orsay, one question has stupefied the predominantly male researchers drawn to the work: ‘Who is the woman in the painting?’[1]

This question about Courbet’s model is the focus of a recent book by the French literature historian Claude Schopp. Entitled L’Origine du monde: Vie du modèle, the book revolves around Schopp’s purported discovery of the woman’s identity, the Parisian dancer Constance Quéniaux. The book’s introduction explains how Schopp came upon this information; her name was buried deep within the stacks at the Bibliothèque nationale inside a letter written by Alexander Dumas. From there, Schopp defends his argument by presenting a careful account of his research, the letters that he reviewed and transcribed as well as his theories about the relationships between Courbet and Khalil Bey and between Khalil Bey and Quéniaux.

The second part of the book can be described as a micro-history. Schopp’s L’Origine du monde: Vie du modèle, functions as a precious document of the life of Quéniaux, a woman whom few would have found interesting if not for her status as the model in Courbet’s infamous painting. His biography of her takes pains to illustrate details about the documents that defined her life, from her birth certificate, to a photographic portrait by Nadar, to the condition of her estate after she passed away. Schopp extends his questions beyond merely ‘Who is she?’ but also to: ‘Where did she spend her childhood? What was her life as a dancer in the Paris opera like? How did she pass her days?’

A second look at the history of L’Origine du monde can help us to better contextualize Shopp’s project. L’Origine du monde is a painting that thrusts the female sexual organ before its viewers. The figure compels viewers to accept an unidealized image of the female sex. Since its first days, L’Origine du Monde, linked to the taboo of female sexuality, has caused anxiety for its male audience. The original owner, Khalil Bey, hid the painting beneath a green curtain and revealed it only for the pleasure (or consternation) of select guests. Lacan, too, hid the painting within a puzzle box, which (tellingly) only Lacan knew how to open. There is a certain poetic justice tied to the painting’s current display in plain view at the Musée d’Orsay. For the first time in its history, the painting requires no mediation. Without its veil, L’Origine du monde gives nothing to mollify the explicit presentation of the female body—no fig leaf or flirtatious gesture conceals her. The woman is at last present.

It is in this context that we receive Schopp’s book. His efforts to apply a name to the faceless figure in Courbet’s painting can be perceived as simply the most recent attempt to soothe the primeval anxieties invested in the work. Through L’Origine du monde: Vie du modèle, Schopp attempts to undo the mystery of Courbet’s painting with the stated objective of giving a name to the woman’s body. Yet, the identification of the model is just another kind of veil. Schopp’s book uses research, knowledge acquired about the model, to give an illusion of his own degree of access to the woman’s painted body. Just as Khalil Bey and Lacan established control over the figure by controlling the visibility of the painting, Schopp, too, positions himself as the gatekeeper before the work. Rather than humanizing the figure, the information Schopp provides in his book gives a false sense that identity can be encapsulated completely by representation. Furthermore, though Schopp describes Quéniaux’s career as a dancer at length, it is clear that his interest in her derives from Courbet’s painting of her genitalia rather than her achievements in the opera.

When it comes to approaching a painting as provocative as L’Origine du monde, the impulse to research the work may prove irresistible, but the form of interpretation matters. Claude Schopp’s L’Origine du monde: Vie du modèle sheds light on the biography of Constance Quèniaux, Courbet’s model and an otherwise unknown woman. However, Schopp’s meticulously researched book serves as just another attempt to establish authority over Quèniaux’s image. The underlying desire to acquire knowledge about Quèniaux, and therefore control, is the true subject of Schopp’s book. For the greater part of its history, Courbet’s L’Origine du monde was hidden in private collections. Now that the painting has found a home in the Musée d’Orsay, it is appropriate to ask: ‘Who is the correct viewer of the work?’ Perhaps it is time to embrace L’Origine du monde as a painting that exists only for itself.

Amber Harper

____________________

[1] See, for instance: Bernard Teyssèdre. Le roman de l’origine(Paris: Gallimard, 1996); Thierry Savatier, L'Origine du monde, histoire d'un tableau de Gustave Courbet, (Paris: Bartillat, 2006). Jr.

The Politics of Painting: Fascism and Japanese Art During the Second World War

ASATO IKEDA

The Politics of Painting: Fascism and Japanese Art During the Second World War

Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2018 144 pp.; 33 color ills., 12 b/w.

$60.00

9780824872120

Asato Ikeda’s book The Politics of Painting: Fascism and Japanese Art During the Second World War offers an important consideration of wartime art. Ikeda, a notable scholar in the field of Japanese art history, often examines the ways that Japanese visual culture intersects with imperialism, war, gender, and sexuality. In her newest publication, she situates 1930s and 40s paintings within the context of Japanese fascism. As Ikeda contends in the book’s introduction, art produced during the Second World War has been largely neglected in Japan. It has only been since the 1990s that scholars have begun critically investigating wartime Japanese art, and almost all of this scholarly attention has been directed toward sensōga, paintings commissioned by the government to record battles. Ikeda instead focuses on paintings that reference Japanese traditions, icons, and culture to reveal the subtle ways that fascist ideology spread throughout Japan in the 1930s and 40s.

Ikeda’s book is comprised of case studies centered on Yokoyama Taikan’s paintings of Mt. Fuji, Yasuda Yukihiko’s Camp at Kisegawa (1940-1941), Uemura Shōen’s paintings of women, and Fujita Tsuguharu’s Events in Akita (1937). Each chapter seeks to uncover the ways that these artworks draw from Japan’s historical and cultural past in order to legitimize the state’s wartime efforts. For example, in “Yokoyama Taikan’s Paintings of Mt. Fuji,” Ikeda argues that Yokoyama’s landscapes resonated with and reinforced Japanese fascism by proclaiming the country’s exceptional cultural identity. Like other fascist governments, Japan’s was characterized by the belief that the country had lost its traditions and “authentic spirit” in the process of modernization. Japanese fascism sought to recreate a national community of people united by the country’s cultural inheritance. Yokoyama drew on the iconicity of Mt. Fuji, a recurring motif in art and literature for hundreds of years, to evoke Japan’s heritage and drum up patriotic support for the government’s efforts to restore Japan to glory.

Ikeda’s exploration of the intersections between fascism and gender in “Uemura Shōen’s Bijin-ga” is particularly compelling. Unlike other scholars who tend to read Uemura’s paintings as anti-war and the artist herself as proto-feminist, Ikeda argues that Uemura’s paintings bolstered the war effort by treating Japanese women as a repository of traditional values, such as self-sacrifice and restraint. For example, the subject of her 1944 painting Lady Kusunoki is a legendary fourteenth-century woman revered for urging her husband and son to fight to the death for the emperor. Ikeda argues that in the context of the Second World War, during which Japanese literature and popular media extolled the honor of women who were willing to sacrifice their sons for the war effort, Uemura’s painting was a highly politicized form of moral education for women.

While each of the case studies is insightful, well researched, and persuasive, the question of artistic agency and intention is not always satisfactorily resolved. In some cases, it is not clear if Ikeda is arguing that the artists were consciously complicit in the spread of fascism. For instance, while Yokoyama’s efforts to raise money for the military and his pro-war writings strongly indicate his support for Japan’s imperialist ideology, Uemura’s personal motivations are more difficult to establish. It would not have weakened Ikeda’s argument to acknowledge the possibility that the artists’ intentions were opposed to those of the state; in either case, their works could act as agents of fascism.

Overall, The Politics of Painting is an important contribution to the literature about wartime art. Ikeda’s skillful analyses of seemingly innocuous artworks reveal the subtle ways that visual culture mediated fascism in Japan before and during the Second World War. Her argument offers a framework for thinking about the ways that ostensibly apolitical artworks participate, either directly or indirectly, in political discourses.