When Space Needs an Advocate

Brittany Webster (’12) brings science to Capitol Hill with the American Geophysical Union.

A view of the Milky Way, from NASA’s Great Observatories in 2009.

When Space Needs an Advocate

Brittany Webster (’12) brings science to Capitol Hill with the American Geophysical Union.

Have you ever heard of space weather?

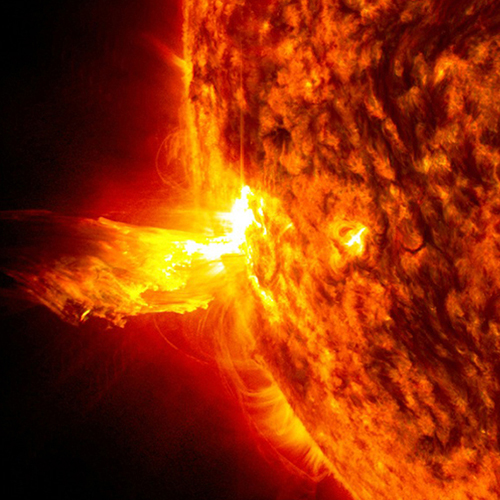

Activity on the sun—solar flares, coronal mass ejections, and high-speed winds—can impact the environment in space and, when directed toward Earth, can affect our atmosphere and technological systems.

In September 1859, an outburst of billions of tons of solar particles traveling toward Earth at millions of miles an hour knocked out telegraph systems across Europe and North America, giving operators electric shocks and, in some cases, sparking fires. Auroras, phenomena caused when such matter interacts with Earth’s upper atmosphere, were visible from the North Pole to Cuba.

It was the largest solar storm ever recorded, but certainly not the last. A solar flare in 1972 brought down long-distance telephone lines across several US states; one in 1989 caused a power outage in Canada that affected six million people, and a 2006 storm disrupted satellite communications and GPS navigation. A report from the National Academy of Sciences estimates that a solar storm of the magnitude that caused the 1859 event has the potential to cause trillions of dollars in long-term damage to these systems.

As a program manager of public affairs with the American Geophysical Union (AGU), persuading Congress to authorize funds to study space weather is one of Brittany Webster’s favorite projects.

“Space weather is something you can forecast,” Webster (’12) says, “but our forecasts just aren’t great yet. So the Space Weather Research and Forecasting Act is meant to fund the research and technology we need to make these forecasts better, and to make sure our government has a plan in place so that if something does happen, agencies know what it is and can react.”

Webster didn’t expect to spend her days talking about science. In many ways, her goal was the opposite. “I have an uncle in the music industry, and we’ve talked a lot about the issues of protecting artists’ rights,” she says, “and being a literature major, I was really interested in those issues, but as it applied to writers.”

Studying comparative literature and international relations at the University of Georgia, her goal was to work behalf of writers on international copyright issues. When it was time to choose a law school, BU Law’s intellectual property law program stood out. It wasn’t until she arrived and started taking classes that her trajectory changed.

She took a legislation course in her first year, and as a 2L participated in the African iParliaments Clinic (formerly part of the Legislative Policy & Drafting Clinic), for which she worked on a bill that considered how countries in East Africa could develop their renewable energy industries. “That’s how I got interested in environmental law,” she says, “all of the sudden, I started to think more about how I could be more involved in the legislative process, especially how legislation is used change behaviors.”

After graduation, she worked as a legislative fellow for Congressman Ami Bera (D-CA), who sat on the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology. In that position, she worked on issues related to NASA and STEM education, and helped markup a bill to fund the National Science Foundation (NSF).

“I hadn’t taken a science class since my freshman year of college,” she laughs, “but I just loved it. I was legislating for people who were literally putting things into space, and there are so many obstacles to that, but these people know how to do it.” Where they needed help, she says, was “demonstrating and talking about why what they were doing was so valuable.”

With the AGU, Webster’s goal is to bring science to Capitol Hill. Her work revolves around appropriations, legislation, and outreach to members of Congress. In addition to the space weather bill, Webster is working on a NASA authorization bill, which sets the policy for the organization for the next fiscal year. She’s coordinating with AGU’s members to understand what they need and working with congressional committee staff to advocate that their priorities be included in the legislation.

Another major project is to bring scientists to Washington, DC, so they can meet with their representatives and advocate for their research on space, climate change, natural disasters, and more. AGU offers training for members new to advocacy and encourages them to engage in the civic process. “It’s really rewarding, because I get to be a policy and political wonk, but there’s nothing like someone telling you that, because of funding from the NSF, they were able to go to college.”

One of the things Webster loves most about her job is the opportunity to get creative when she connects with a congressperson or their staff on an issue. For example, while not every congressperson is on the same page about how to address climate change, there’s still a way to make progress.

“When we go into offices, I don’t need to talk about climate change to talk about sea level rise in coastal communities, because that’s a reality,” she says. “We don’t need to debate whether climate change exists if you’re there to talk to me about what we can do about it or about why this kind of science is important.”

Finding a way to move people to the next step is part of the challenge. “I have never walked into an office and been told, ‘we don’t like science,’” she says. “So, it’s more about how I can get people excited about science, and then take that excitement and turn it into something actionable.”