Securing the Vote

Students from the BU/MIT Technology Law Clinic help MIT researchers disclose vulnerabilities in a smartphone voting app.

Securing the Vote

Students from the BU/MIT Technology Law Clinic help MIT researchers disclose vulnerabilities in a smartphone voting app.

Less than two weeks after a smartphone app wreaked havoc on the Iowa Democratic caucuses reporting process last month, researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, with help from BU School of Law’s BU/MIT Technology Law Clinic, released a new paper casting even more doubt on internet-based election technologies.

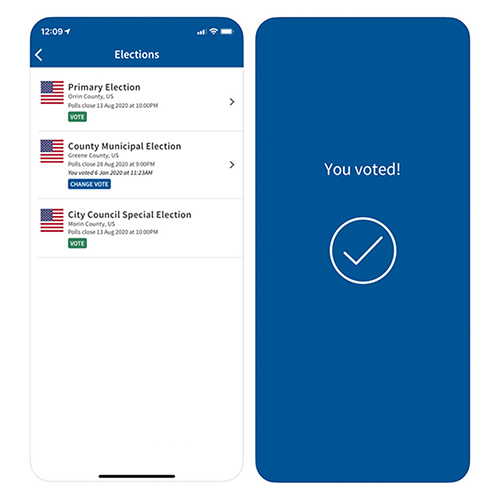

The MIT team’s research did not address the app used in Iowa, where technical mishaps seem to have been the cause of the problems. Instead, the researchers took aim at security vulnerabilities within a different app called Voatz, including the potential for hackers to change, prevent, or reveal how an individual has voted in an election.

The public disclosure came after weeks of private discussions between the researchers—PhD students Michael A. Specter and James Koppel and research scientist Daniel Weitzner—and personnel from the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), a new entity within the Department of Homeland Security. Those discussions were facilitated by the Technology Law Clinic, which worked with the MIT researchers on how to disclose their findings. Through CISA the researchers were also able to share information with representatives of Voatz and officials in states that have already used or plan to use the app in elections.

“We moved with some real haste in contacting CISA,” says Andrew Sellars, director of the clinic, noting the “national significance” of election-related security concerns. “Our clients really wanted to be quite intentional with how they were handling their discoveries.”

Three BU Law students—John Dugger (’21), Quinn Heath (’21), and Eric Pfauth (’20)—were on the team helping the MIT researchers bring their findings about Voatz to light, and the work is already having an impact. On February 13—the same day of the paper’s release—one Washington state county that planned to use Voatz had already decided against doing so. Not long after, West Virginia dropped the technology.

“It’s rewarding to see what we worked on have an impact,” says Dugger, who started as a fellow in the Technology Law Clinic last summer. “The paper wouldn’t have been released if it weren’t for our assistance. It’s great to know that we had a hand in that.”

After the MIT researchers signed on as clinic clients, the students, Sellars, and Visiting Clinical Assistant Professor Tiffany C. Li began discussing how to responsibly reveal the vulnerabilities that were discovered in the voting app. Dugger says he and the other students examined relevant laws around software reverse engineering and security research. They also explored how best to utilize CISA, which was created in 2018 in part to counter election interference.

“All in all, it was a very constructive discussion with CISA and affected elections officials,” Sellars says. “We were quite happy with that process and with the substance of what we heard from them.”

Sellars says he found Voatz’ response less satisfactory. After the paper’s release, the company posted a message on its blog, claiming there were “fundamental flaws” with the MIT researchers’ method of analysis. What they didn’t do, Sellars notes, was say the researchers’ findings were inaccurate.

“They’ve thrown up a lot of sand about the research,” Sellars says. “But what’s most telling is that they don’t refute the findings. They haven’t actually said ‘that isn’t true.’”

We shouldn’t subject people to untested experiments on their votes. If we’re going to give them the vote, let’s give them the vote. A paper ballot is always going to be the most secure.

One reason government officials are so eager to embrace online voting technology is to make participating in elections easier for people with disabilities. A person who can’t make it to the polls may more easily be able to cast their vote via a smartphone. But Sellars says accessibility shouldn’t come at the price of individual privacy and election security.

“We shouldn’t subject people to untested experiments on their votes,” he says. “If we’re going to give them the vote, let’s give them the vote. A paper ballot is always going to be the most secure.”

MIT scientist Weitzner agrees.

“We all have an interest in increasing access to the ballot, but in order to maintain trust in our elections system, we must assure that voting systems meet the high technical and operation security standards before they are put in the field,” he told MIT News.

(Sellars and Weitzner are not alone: In 2018, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine issued a report calling on all US elections—at every level—to be conducted with paper ballots by 2020 to protect against security breaches.)

The Technology Law Clinic regularly assists BU and MIT students whose work touches upon intellectual property, data privacy, civil liberties, or media and communications laws (another entity, the Startup Law Clinic, offers legal guidance for BU and MIT entrepreneurs). Although Technology Law Clinic students have handled so-called “vulnerability disclosures” in the past, the Voatz vulnerabilities were particularly high profile, especially coming so closely on the heels of the caucus app in Iowa.

Visiting Professor Li, who worked closely with Sellars and the students on the Voatz research disclosure, says the case is a “great example of the unique partnership between MIT and BU.”

“Most student and early career cybersecurity researchers do not have access to free legal services,” she says. “In addition to strengthening partnerships like the BU/MIT clinics, we also need to think of new legal approaches nationwide to protect researchers like our clients.”

Dugger agrees, saying both technical know-how and legal expertise are needed to bring critical information to the public.

“We’re focused on different pieces of the puzzle that fit together really nicely,” he says.

This Series

Also in

Voting in 2020

-

October 31, 2024

Politically Inclined

-

October 20, 2020

The Fight for Fair Elections

-

October 20, 2020

A Chaotic Primary