Webinar Summary – “Small is Beautiful”: A New Era in China’s Overseas Development Finance?

By Hua-Ke (Kate) Chi

On Thursday, January 26, the Boston University Global Development Policy (GDP) Center hosted a webinar discussion for the 2023 update of the China’s Overseas Development Finance (CODF) Database, a global, harmonized, validated and geolocated database recording loan commitments from two major development finance institutions (DFIs) in China, the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM). The webinar featured Rebecca Ray, Senior Academic Researcher, Kevin P. Gallagher, Director of the GDP Center, Cecilia Springer, Assistant Director of the Global China Initiative, and Oyintarelado (Tarela) Moses, Database Manager and Data Analyst.

Ray began the webinar by introducing the CODF database. The CODF Database records a total of 1,099 development finance commitments made from CDB and CHEXIM to 100 countries, totaling $498 billion between 2008-2021. This level of lending represents 83 percent of World Bank sovereign lending in the same time period and places CBD and CHEXIM among the most active DFIs in the world. Loans have been made on nearly every continent, with concentrations in Southeast Asia, Africa and South America. China’s development finance has been concentrated among its top ten borrowers — Angola, Argentina, Bangladesh, Brazil, Ecuador, Iran, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Russia and Venezuela — which account for 59 percent of total loan commitments. In addition, loans to five of these top ten borrowers have gone to major oil and gas state-owned enterprises and public-private partnerships.

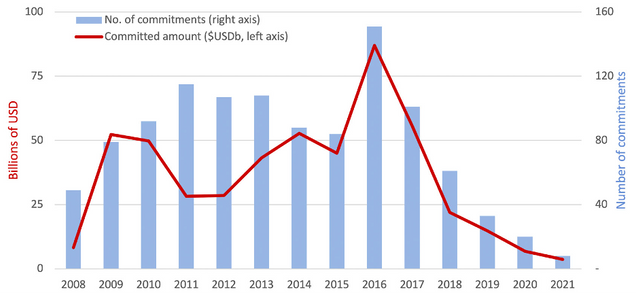

Ray then explained key findings from this year’s database update. She underscored that international sovereign loan commitments from CBD and CHEXIM have shown a tremendous decline since 2016 (see Figure 1). In 2020 and 2021, the CODF Database recorded 28 sovereign loan commitments at the total value of $10.5 billion, the lowest level in recent years, demonstrating the new “small is beautiful” approach to lending: as Chinese overseas development finance has fallen in total value, so has the average loan commitment size, with respect to aggregate monetary value and in the geographic footprint of financed projects.

Figure 1: China’s Overseas Development Finance by Year, 2008-2021

This trend supports the idea that most borrowers treat China as a complement to traditional development lenders, while also heavily borrowing from the World Bank. In particular, developing countries borrowed significantly from both the World Bank and China during and after the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, as well as the early years of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), effectively treating these two sources of development finance as complements.

In addition, Ray highlighted that many of China’s major borrowers like Pakistan, Bangladesh, Brazil and Argentina also borrow in large amounts from the World Bank.

Furthermore, the sectoral composition of projects shows a wide distribution of Chinese and World Bank development finance, demonstrating stark differences across sectors. Most of the World Bank’s lending, at approximately 63 percent, has supported public administration and discretionary sector, which includes health, education, water and wastewater, poverty alleviation, security and other general government support. In contrast, the top sectors for Chinese lending have been extraction and pipelines, transport and power, which together account for 66 percent of their lending to support borrowing countries’ immediate economic growth.

To analyze environmental and social risk profile of China’s overseas development finance, Ray investigated the sensitive territorial overlap of project finance over time. The CODF Database maps 736 projects in 85 countries within 25 kilometers precision for spatial analysis. In particular, sensitive territories of critical habitats for biodiversity, Indigenous peoples’ land and national protected areas are taken into consideration in the database. These territorial categories do not encompass all types of social and environmental risks that development lenders may face, but their global definitions allow observers to track trends in these broad areas of social and environmental governance across regions and over time. From 2008-2021, approximately one-third, 34 percent, of Chinese overseas development finance with high-precision geolocation supported projects that overlapped with at least one type of sensitive territory. This is a significant decline from the previous five years, when 71 percent of financed supported projects overlapping at least one type of sensitive territory. Over the entire 14-year study period, Ray highlighted that 47 percent overlapped with possible or likely critical habitats, 30 percent overlapped with national protected areas and 28 percent with Indigenous peoples’ lands.

Figure 2: Chinese Overseas Development Finance: Overlap with Sensitive Territories, 2008-2021

Ray further added that the significant difference in the representation of critical habitats and other types of sensitive territory is not simply due to different scales of each type of territory. Globally, critical habitats and national protected areas individually cover 15 percent of land and inland waters, while Indigenous peoples’ lands represent over 25 percent of the world’s land surface. However, legal protections and environmental standards differ significantly across territory types. National protected areas are recognized, delineated and managed for conservation, although specific regulations vary regarding the types of permissible activities within their boundaries. In contrast, critical habitats do not enjoy specific legal protections, though they have been recognized by conservation biologists for their value for biodiversity. Indigenous peoples’ lands are in a middle ground of legal protection, with varying legal protections across different countries. Thus, the greater concentration of projects in critical habitats than in national protected areas or Indigenous peoples’ lands may signal a difference in host country legal protections for these types of territories. This finding supports other GDP Center research showing the importance of host-country environmental and social standards in cultural and biological diversity hotspots such as the Amazon basin and Indonesia.

Ray concluded by sharing prospects of Chinese overseas development finance. Based upon recent trends recorded in the CODF Database, Ray anticipated that it may be unlikely for Chinese overseas development finance to return to the highest levels seen in 2016 in the near future. While the COVID-19 pandemic continues to hamper economic activity, China has prioritized support for its domestic economic growth while restricting lending abroad. In host countries, high debt burdens have limited space for additional borrowing during the pandemic as well. Nonetheless, China’s capacity for outbound development finance is recovering and the incentives and capacity of overseas development finance to rebound is subject to change as China reopens its borders. As new deals with Argentina, Pakistan and others come to fruition, the Boston University Global Development Policy Center will track these financial commitments for inclusion in future updates to the CODF Database.

Following Ray’s introduction and summary of key findings, Tarela Moses demonstrated how to use the CODF Database, presenting the interactive mapping interface which geospatially showcases China’s overseas development finance projects and their overlaps with environmentally sensitive territories. She also demonstrated how to navigate through individual development finance projects in which further information of the lending including year, amount committed and project sectors are recorded.

Next, Cecilia Springer moderated a discussion among Kevin Gallagher, Ray and Moses. Gallagher shared key takeaways for policymakers with respect to recent trends in China’s overseas lending as China has filled the financing gaps for developing countries since 2008 and contributed to major economic growth in these nations. Yet, data suggests that such financing has gradually declined in dollar amount while the environmental and social risk factors of these development finance projects may be lower. Policies implemented by China have also suggest the commitment towards less carbon-intensive project finance. Additionally, Gallagher highlighted that there may be an increase in alternative forms of financing available offered by China, such as an array of equity funds, e.g., Silk Road Fund and China-Portuguese Speaking Countries (PSCs) Cooperation and Development Fund. Gallagher highlighted that equity financing may create less of an impact on debt distress in the Global South and as emerging markets face growing debt challenges, such funds may play an increasingly critical role in overseas development finance. To add, Moses and Ray discussed future prospects of China’s development finance, considering the end of the zero-COVID policy and recent natural gas shortages in China. The mismatch in China’s and host countries’ incentives towards development finance may catalyze a more diverse portfolio of financing options established by public or private stakeholders.

Ray further emphasized the prospective trends of lending in which bilateral development finance institutions’ support is complemented with greater equity investment directly from Chinese firms. This allows Chinese companies to gain immediate and direct experience through different economic and regulatory environment in host countries, which aligns with the initial goal of expanding investment footprint outlined in the Belt and Road Initiative. Ray also recognized the World Bank’s “Evolution Roadmap” in 2023 to address development challenges which may have an effect on its vision and participation in global development finance.

Gallagher then shared insights on China’s role in acute global sovereign debt crisis as loans materialized and the estimation of 68 countries in need of financial relief from research conducted by the United Nations Development Programme. China is one of the most significant creditors and was a leader in 2020 and 2021 in suspending debt; however, China has thus far been reluctant to sufficiently adjust debt structures in order to achieve financial relief and support debt sustainability in borrowing countries and their economic recovery. Therefore, the arrangement of a global reform may be necessary to compel debt restructuring in the interest of both creditors and debtors in the near term.

Lastly, during the Q&A session, the participants fielded questions on the scope of the datasets, the geolocations of infrastructure finance reported in the CODF Database and China’s lending patterns in comparison with other development finance institutions.

Explore the Data Read the Policy Brief*

Hua-Ke (Kate) Chi is a Research Assistant with the Global China Initiative at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center and a graduate student in the Department of Economics at Boston University.

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Global China Initiative Newsletter.