A Primer on Massachusetts’ Two Ballot Questions: the “Right to Repair” and Ranked-Choice Voting

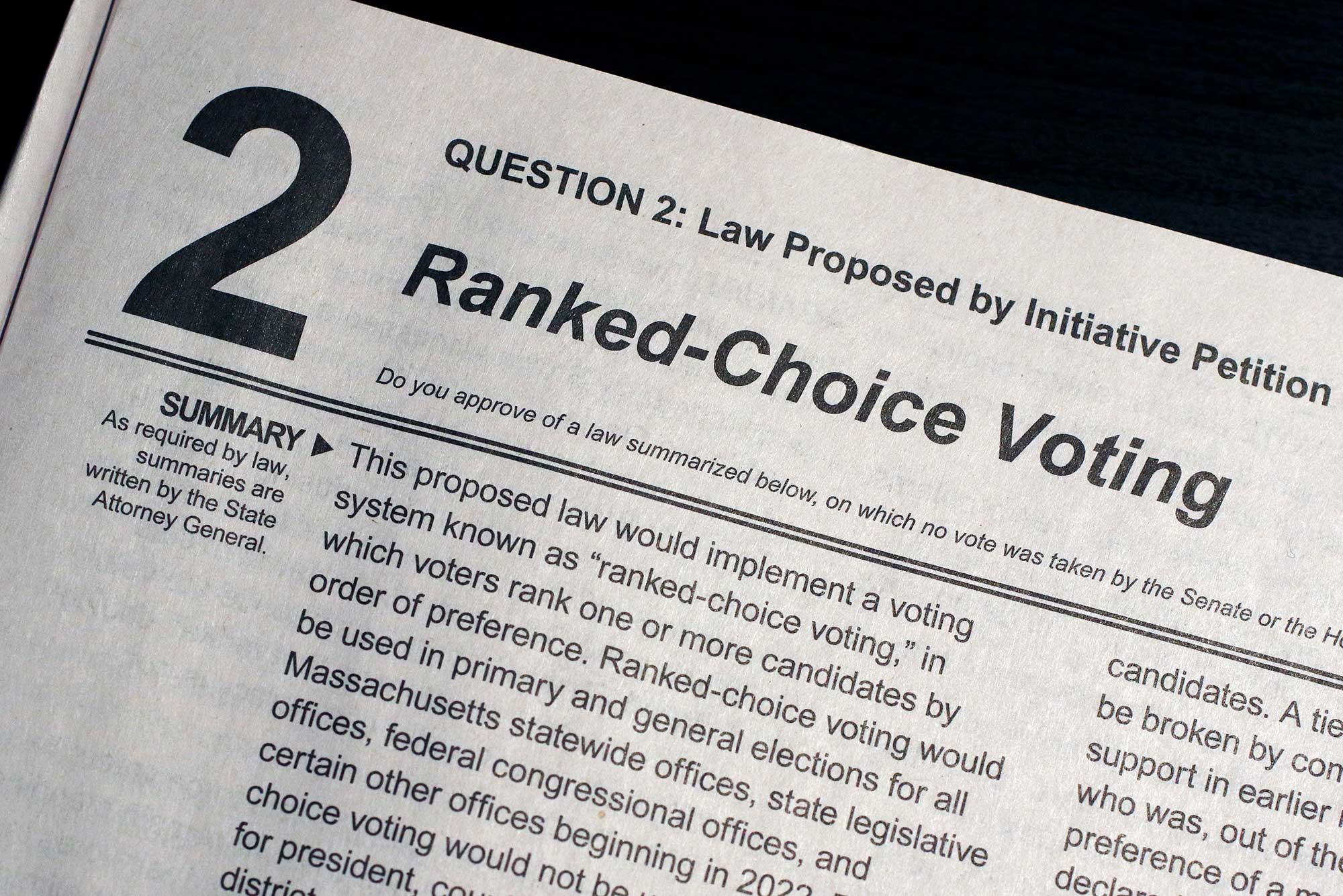

A Massachusetts ballot question asks voters if they want to rank candidates in order of preference for future elections. Photo by AP/Bill Sikes

A Primer on the Two 2020 Massachusetts Ballot Questions

Voters will consider car owners’ “right to repair” and ranked-choice voting

- The pros and cons of both Massachusetts ballot questions November 3

- Massachusetts Ballot Question 1: Should carmakers share more repair data?

- Massachusetts Ballot Question 2: Should the commonwealth have ranked-choice voting?

In the politics-is-scarier-than-horror-movies department, this current TV ad is Exhibit A: a woman in a dark, lonely parking garage, about to get in her car, is seen from the perspective of a predator creeping up on her.

Who knew choosing an auto repair shop could be so dangerous?

Opponents of the so-called Right to Repair law, one of two binding ballot questions Massachusetts voters will decide November 3, warn that if approved, the law will expand sharing of car repair data in ways that could jeopardize public safety. Supporters call that a fake boogeyman thrown up to inhibit consumer choice.

The second ballot question involves ranked-choice voting, where voters aren’t confined to a single preferred candidate, but instead list candidates in the order they prefer them. Herewith, a primer on both. (A third question, on whether Massachusetts should shift to 100 percent renewable energy use in the next two decades, is an advisory referendum only.)

Massachusetts Ballot Question 1: Right to Repair

No, you’re not losing your mind: Bay Staters already passed Right to Repair eight years ago, requiring carmakers to provide independent repair shops with the same computerized information that the manufacturers’ dealerships use to diagnose and fix problems in their models. Independent mechanics can plug into your car’s onboard data portal to get that info.

But technology has advanced markedly since then, such that 90 percent of new cars have built-in systems for collecting and transmitting mechanical data to automakers wirelessly—but not to independent shops. The ballot question, if approved, would require carmakers to outfit every car, beginning with 2022 models, with an open-access platform for mechanical data, available to car owners and local repair shops.

But a report by WBUR, the University’s National Public Radio station, notes that this is, for now, a solution without a problem. Telematics allows manufacturers to ping your phone or dashboard with an alert that something may need fixing, but there’s nothing to stop you, under current law, from getting that thing checked by your local garage (although if the carmaker can offer you a discount on the repair when it alerts you, that gives them a leg up on your business, according to independent repair shops. And they’re the ones funding the vote-yes side, WBUR reports).

What about the vote-no side’s ads about predators? The proposed law specifically requires sharing “mechanical data” only. But WBUR cites Right to Repair opponent Conor Yunits, who told the station that “the ‘mechanical data’ language in Question 1 could be interpreted to include location information, because driving in certain environments—the salty sea air of Cape Cod, for example—may corrode parts of a vehicle. If a vehicle were to transmit location info to a shared database, that could create ‘personal safety risks,’ Yunits argued.”

Supporters of Question 1, like the Boston Globe’s editorial board, retort that the possibility of hacking exists now, for a database accessible to hundreds of dealerships. But expanding that access is precisely why the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration is nervous about Question 1, warning that the measure “might open up a whole host of cybersecurity risks, including the possibility of hackers—or ‘malicious actors’—exploiting the broader wireless access to vehicle systems and causing crashes by seizing control of a vehicle’s braking and acceleration.”

The Globe concedes that if voters approve the question, “the Legislature must follow up to better regulate telematics and ensure that all connections to vehicles are as safe and secure as possible.”

Supporters and critics have spent millions of dollars to sway voters, flooding the TV market with political ads for and against. By early October, the “Yes” side had spent $16.6 million, the “No” side, $15.5 million.

Massachusetts Ballot Question 2: Ranked-Choice Voting

It’s an age-old voter complaint: I love Candidate A, who doesn’t stand a chance, while Candidate B, whom I sort of like, does. If I vote my conscience for A, Candidate C, whom I loathe, will likely beat B and win the election.

Hoping to sidestep such dilemmas, some jurisdictions—including several Massachusetts municipalities and the state of Maine—use ranked-choice voting, which would let that hypothetical voter rank their choices on their ballot in order of preference: A, B, C. If no candidate wins a majority of first-place votes, the candidate with the least votes is eliminated, and his or her votes are redistributed to his or her voters’ second choice. This goes on until one candidate has a majority.

Question 2 would put this system in place, starting in 2022, for primaries and general elections for statewide offices, and for certain state and federal legislative offices. It wouldn’t be used in elections for school committee, county commissioner, or president, but could be expanded someday to those contests, advocates say.

“If your favorite candidate doesn’t win, your vote is instantly counted for your second choice so candidates must compete for every vote,” reducing polarization, advocates write in the state’s voter information guide. “Ranked-choice voting ensures the winner has majority support and reflects the true will of the people.” Supporters as varied as Bill Weld, former Republican governor, and Deval Patrick (Hon.’14), former Democratic governor, back the measure.

Opponents worry that ranked-choice voting is too complex, requiring voters to bone up on a potentially crowded bench of candidates for some races. In the voting guide, they note that Jerry Brown, former California governor, vetoed a similar plan in 2016 on the grounds that it was “overly complicated and confusing,” potentially discouraging voter participation.

A judge discounted that argument in a challenge to Maine’s ranked-choice law—the only statewide system in the country—saying it was based on “wobbly demographic data.” Still, the Boston Globe reports, Maine’s law has not fulfilled advocates’ dreams of draining big money and uncivil campaigning from politics.

Supporters of the question, financial or otherwise, include the Massachusetts Democratic Party, the League of Women Voters, the Massachusetts Immigrants and Refugees Advocacy Coalition, and some CEOs and advocacy groups. The Globe endorses a yes vote. The vote-no side is supported by fiscal conservatives, including the Massachusetts Fiscal Alliance, some of whom say the state would be better off adopting runoff elections instead.

This Series

Also in

-

November 7, 2020

Joe Biden Defeats President Trump, Clearing the Way to Becoming 46th US President

-

November 7, 2020

How Does the Electoral College Work and Other Election Questions

-

November 7, 2020

Joe Biden Will Be the Oldest President Elected. Is That Worrisome?

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.