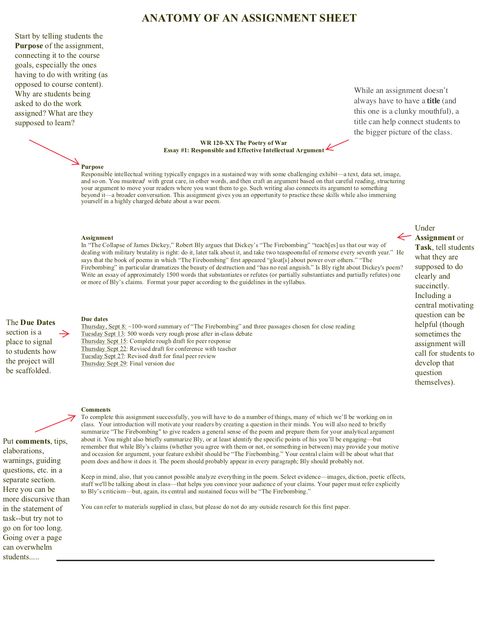

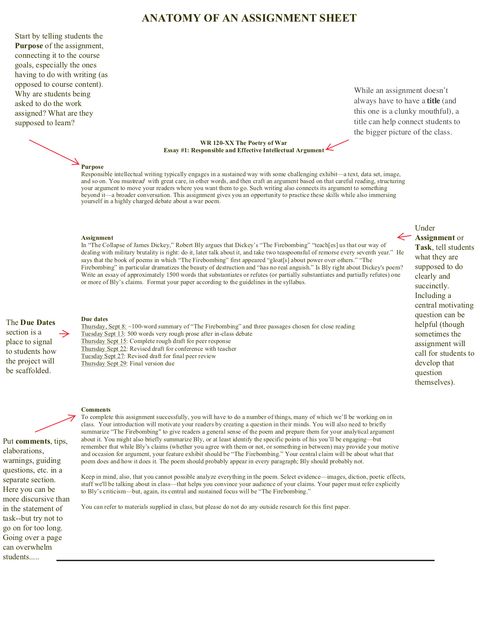

In this guide, we invite instructors to think through the different sections of an assignment sheet and perhaps take a fresh look at their own assignment sheets. At the bottom of the page, you’ll find some insights into more effective assignment sheets from Writing Consultants working in the CAS Writing Center.

Key Elements

Things to Consider

- While an assignment does not necessarily have to have a title (this one’s a clunky mouthful), it can help students connect an individual assignment to the bigger context of the class.

- Start by telling students the purpose of the assignment, connecting it to the course goals, especially the ones having to do with writing as opposed to course content. Why are students being asked to do the work assigned? What are they supposed to learn?

- The due dates (or submission guidelines) section is a chance to draw students’ attention to how the assignment will be scaffolded.

- Under assignment (or task), tell students what they are supposed to do clearly and succinctly. Including a central motivating question can be helpful, though sometimes the assignment will call for students to develop that question themselves.

- In the comments section (or additional information) you can include elaborations, warnings, guiding questions, etc. in a separate section. Here you can be more discursive than in the statement of task, but try not to go on for too long. Going over a page can overwhelm students.

Additional Resources

Tips from Tutors: What Writing Consultants Say About More Effective Assignment Sheets

In January 2021, a panel of articulate and insightful consultants from the CAS Writing Center spoke to faculty about assignment sheets. Working with students one-on-one on a daily basis, Writing Consultants see assignment sheets from a wide range of courses and instructors, and these consultants were able to draw on their experience to help faculty understand what elements make assignment sheets easier for students to parse.

Keep assignment sheets short (~1 page if possible).

- Students genuinely want to understand what’s being asked of them, but if there is too much information, they don’t always know how to prioritize what to focus on.

- Focus on specific questions you want students to answer or tasks you want them to complete. Avoid content that isn’t specifically related to the assignment itself.

- It’s generally best not to include all assignments for the semester in a single document. While it can be helpful to have one sheet or section of the syllabus with all assignments listed, it’s best to give each assignment its own document with detailed expectations.

- Students need some guidelines for assignments. Following the WP “anatomy of an assignment” guidelines (above) helps students as they move from one WR course to the next, and it also helps consultants figure out where to find key information more quickly.

Give students some choices, but be (overly) clear about your expectations.

- It’s especially challenging for WR 120 students to come up with their own “research question” and then answer it. If you’re asking them to do that, be very specific about what you want them to do and what parameters they should work within.

- Don’t give students a long list of questions to consider — or, if you do, be incredibly explicit about what questions are intended to generate ideas as opposed to what questions they actually need to answer in their paper.

- The best assignment sheets tend to be those that give students a set number of options and then ask them to pick one to answer.

Give clear (as in legible and also as in straightforward) feedback.

- Provide typed rather than handwritten comments.

- Avoid cryptic feedback like “awkward” or “?” that could be interpreted in different ways.

- If you write comments in shorthand, be sure to provide students with a key.

- Provide feedback as specific questions that students can either address themselves, or discuss with a writing consultant (or you!)

Remember WR courses are introductory courses.

- Choose course readings for written assignments that lend themselves to teaching writing as opposed to seminal texts or your personal favorites.

- Go over all readings that students are expected to write about in class and devote extra time to particularly challenging ones. If you are working on difficult topic and/or dense texts, don’t assume your students can navigate them without explicit scaffolding in class.

- Not all students have been taught how to analyze quotations and use them as evidence to support their argument, so be sure to spend time teaching these skills.

- Don’t take anything for granted. Students are coming from all kinds of educational backgrounds, and our courses meant to reinforce (but sometimes teach for the first time) skills all students will need for future college papers. You may also want to read about the “hidden curriculum” in writing classes when considering inclusivity and assumptions.