Redefining Progress

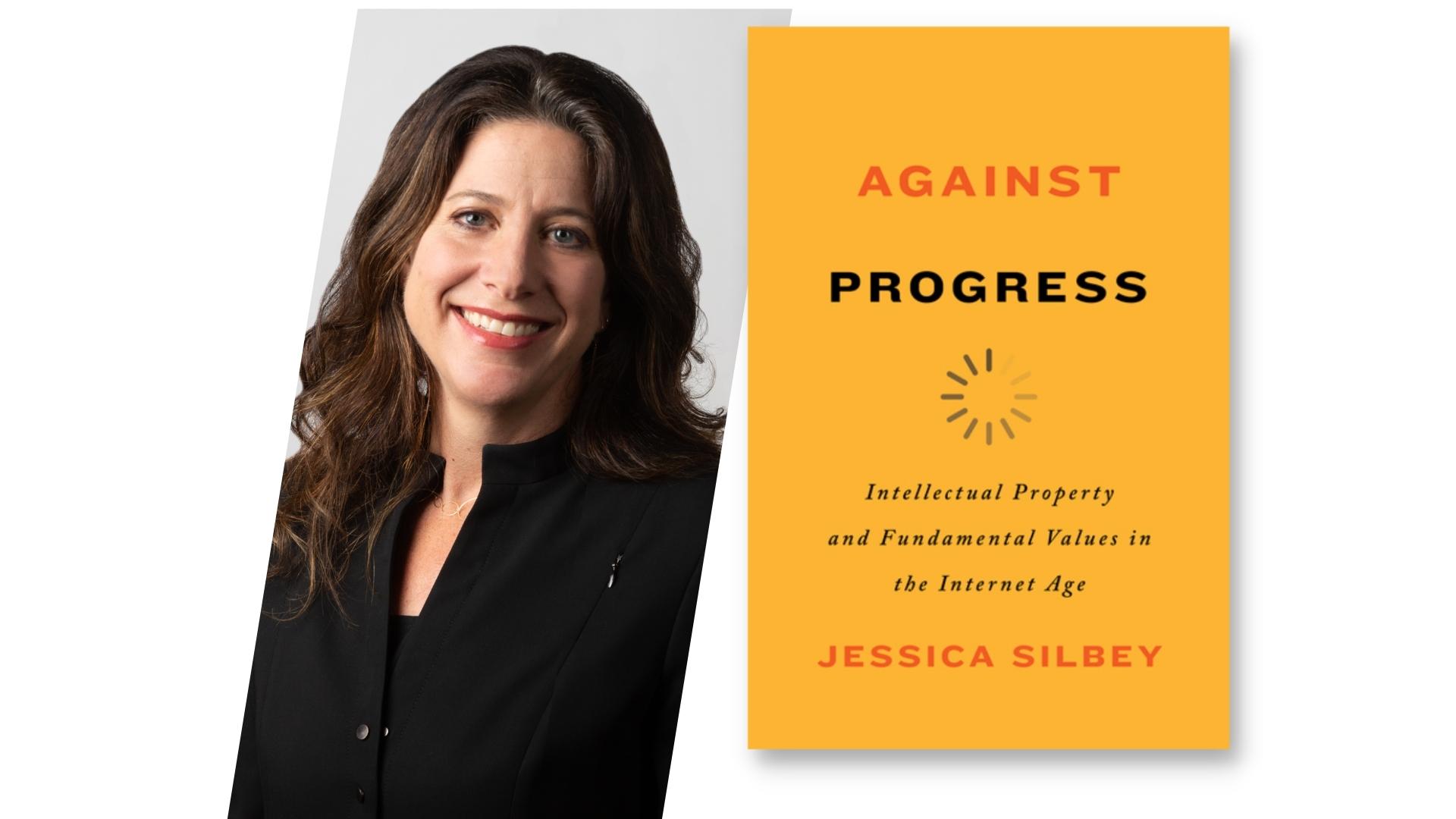

BU Law Professor Jessica Silbey's new book explores how intellectual property law may evolve in the 21st century to underscore fundamental values.

Redefining Progress for Intellectual Property Law

Earlier this month, The Record spoke with BU Law Professor Jessica Silbey about her recently published book, Against Progress: Intellectual Property and Fundamental Values in the Internet Age, which explores how intellectual property law may evolve in the 21st century to underscore fundamental values, such as equality, privacy, and distributive justice.

Listen to an unabridged version of the interview:

Q&A

Jessica Silbey

The Record: How did your research for the book begin?

In the process of writing my previous book, The Eureka Myth, many questions arose. And as it is with scholarship, you start a project, and you put to the side some questions for later.

In the first book, I was studying creative and innovative communities like farmers, pharmaceutical researchers, or painters, and trying to figure out how intellectual property works or doesn’t work for them as a regular matter. In the process of studying law on the ground, rather than law in the courts, I started thinking about the progress clause of the Constitution, which grants Congress the power to create copyrights and patents, specifically for promoting progress of science and the useful arts.

As I was listening to these communities talk about how they wanted to pursue excellence in their work, I started thinking about the relationship between their professional goals and what “progress of science and the useful arts” might mean in the Constitution in 1789. How that word, “progress,” might evolve over time regarding creative and innovative communities.

The Record: The title of your book, Against Progress, suggests that intellectual property law may be hindering evolution, specifically in our digital world. Could you illustrate some of the everyday ways in which we are affected by industries that are leveraging IP law to prevent growth?

The title is supposed to evoke a particular form of progress that intellectual property laws have promoted, which is accumulation for its own sake. That it is about wealth aggregation, without regard to distributional effects or other values, like equality or privacy. The word progress was understood in a very particular way and is being rethought as the 21st century unfolds.

I’ll give some examples. A person may buy an object that has patents in it, like your phone, and they are allowed to resell the thing that you own. This is called the first sale doctrine, and it’s important because it allows us to resell the things we buy. It also gives us the freedom to open our phone and repair it. However, patent law prevents you from making copies of the invention (copying the phone itself and its inner workings). But sometimes those behaviors – resale, repair, and copying – overlap making the freedom to use and repair a risky business. That is bad for consumers.

Another example: There was a farmer named Vernon Bowman in Indiana, who used Monsanto soybean seeds, which are resistant to crop destroying disease. Bowman, like a lot of farmers struggling to make a living, planted the seeds, reaped the harvest, and sold those soybeans that he grew. According to Monsanto’s small print on the bag of seeds, this is allowed. But then he also saved some of the soybeans he grew to use as seeds to replant for the late harvest crop, a risky crop because of its uncertain yield.

Monsanto sued him for using a small part of his harvest as seed, saying Bowman was replicating the seed and replacing the sale of Monsanto seeds in the marketplace with his own newly grown seeds. But the problem with Monsanto’s position is the soybean grown from the seed is both soy and seed. Monsanto asserted patent law only for the seed use when there is in fact no distinction

Monsanto is not wrong technically. But seeds replicate themselves. And farmers have been saving seeds for centuries, that is what farmers do.

Stepping back, there is something perverse about the idea of patent law getting in the way of farmers who barely make a living when the product that they’re buying and using is self-replicating. Monsanto controls about 92% of the soybean crops in the United States. I don’t think they should be suing an individual farmer when he’s saving seeds for the third crop of the harvest, and he’s otherwise been buying Monsanto seeds. Monsanto won that Supreme Court case in 2013. That’s one example of patent law getting in the way of a kind of distributional progress and losing sight of the purposes of patent law and social progress on a broader scale.

I can also talk about copyright law, which prevents the copying of authorial expression without permission of the author or owner of the copyright. There are exceptions to that, which include criticizing the work or parodying the work. Today, there’s a lot more talkback from everyday users of the internet. And what we’re seeing in copyright law is a lot more authorial challenges to being quoted in a critical way. You could think about memes, or blogs where you’re quoting paragraphs from a novel – all those ways of talkback are supposed to be forms of free speech that copyright law allows and promotes. But we are seeing more and more copyright cases that are about censoring speech one doesn’t like rather than engaging debate. That’s another example of how intellectual property law is being misused against its original intent.

The Record: You recently wrote an op-ed about lessons we can take from intellectual property law to protect abortion access. In the month since the Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, are you seeing any parallels in the ways people have used IP cases to fight for fundamental rights?

Current debates around fundamental rights, be it about reproductive justice, speech, or voting, are surfacing debates in our culture about these very issues. Intriguingly, we are seeing the same debates about fundamental values happening in the IP cases. These are unusual places for us to fight about bodily autonomy or privacy questions. We don’t often think about intellectual property in those terms.

But there are many cases that are being brought at the Supreme Court and the higher courts about copyright, patents, and even trademarks, that resonate with questions of privacy, self-determination, and equal treatment. The IP cases that are usually about market competition or earning a fair return on your labor are being debated in terms that are more resonant with what we think about as civil rights and fundamental rights. This suggests that we are experiencing a cultural moment in which many legal fields are being disrupted by these national debates over fundamental values.

The Dobbs decision that overturned Roe v. Wade is forcing people who care about reproductive justice to think about how to mobilize on a state-by-state basis, and how to think more locally about issues concerning access to essential health care. We went from a federally protected right to fighting about the scope of the right on a state-by-state basis. What’s different about intellectual property, especially copyright and patent law, is it as a federal law. There are no state copyright or patent laws. So the way to address injustice in the federal law if it cannot be changed, is to think about how to sustain creative and innovative work on a local level. Not outside IP systems, but next to them or in connection.

For example, I often consult with writers’ groups and artists collectives on how to help them get fair housing deals or tax breaks to help them sustain their work when the IP systems don’t work for them. So, there’s a parallel in going local when the larger legal system is not helping you.

A lot of the debates we’re having about fundamental values are driven by a profound imbalance in our society regarding wealth and access to resources. And recognizing our interconnectedness, that we depend on a lot of people to live our life, would go a long way to resetting that balance.

The Record: Did anything surprise you while researching for your book?

Surprise may be the wrong word. I’m so grateful and in awe of the people that I interviewed. I did a case study on digital photographers who make the most extraordinary pictures. As users of the internet, we consume photos more than anything else. Photographs are the most trafficked digital item on the internet.

We rarely think about the people who make those photographs. I learned how hard it is to make that work, how generous they are to let it circulate without any password-protected website. We look at these images all the time, and we learn about the world through them, and photographers are a gift to us. Photographs have been important in understanding the history of our country, our world, and connecting people to each other. We all take pictures with our phones and think that we’re photographers. The difference between an ordinary photograph and an extraordinary photograph is tremendous. And I have a renewed appreciation for that kind of aesthetic and communicative forms.

The Record: What advice would you give to artists or innovators about IP?

My advice may sound self-serving, but the way that we all need to have a doctor, I wish that all creators and innovators had a lawyer to call to do a check-in: “Can I do this? Should I do this? How do I do this? What should I be worried about?”

And I wish lawyers weren’t so expensive, and that people weren’t so afraid of them. Checking in early helps smooth the way for the good work to be done. I hope that my students, and the artists and innovators that I work with, will meet more in the middle to do good work together.

I don’t want law to be an impediment. I believe that law can be a force for good.

A lot of the debates we’re having about fundamental values are driven by a profound imbalance in our society regarding wealth and access to resources. And recognizing our interconnectedness, that we depend on a lot of people to live our life, would go a long way to resetting that balance. Like we need taxes for roads and schools, we need a public domain of information and cultural resources to share and rely upon, we need lawyers too to be accessible, not only in emergencies, but every day. It’s hard to remember that. But we need to try.

The Record: Do you see a need for balancing this free exchange of ideas, information, and speech with equality and privacy?

We only talk about balance when things get imbalanced. And part of what’s wrong with intellectual property today is that it has these individualistic extremes, thinking about the garage inventor or the solo author and glorifying that is totally a myth. Nobody invents or creates alone. There is more co-invented and co-authored creativity and innovation that our IP system sustains. Another extreme concerns who benefits from intellectual property: giant companies and aggregators of intellectual property as assets. There should be more of a spectrum of beneficiaries than just corporations that hold assets.

So, one of the things that’s missing from that conversation is the way organizations, institutions, and specific communities develop their own rules or norms around sustaining their individual members as a way of achieving a larger goal of creative and innovative work. It’s not just individuals or big companies. It’s lots of in-between, and it’s often outside the formal legal rules.

If you think about the university, for example, as an institution that benefits from IP, but also can get hung up by IP, the institution can create its own rules to benefit its members. Intellectual property does not do a very good job at that middle ground, facilitating the organizations and institutions in which we all work and live. If we’re talking about particular forms of law reform, these are essential organizations that form our society, and IP laws could support them, not the individuals, and not the giant companies. But more of these everyday institutions that are essential to social progress.

The Record: Is there anything that you’d like to address that we didn’t get to discuss?

I’m starting a new book, which comes from this book, tentatively called “IP’s Edge.” I’m exploring the edges of intellectual property – be they artificial intelligence created art and innovation, or the things that are not protected and particularly excluded from intellectual property, like facts, ideas, natural processes, or things that cannot be protected through IP at all, that are in the public domain.

And I’m thinking about the development of IP and about what is outside IP? What is the public domain, how important is it? What is the role of machines and automation in the future of creativity and innovation? There’s a lot of hope in these spaces right now to think about revitalizing the public domain at IP’s edges. So, I’ll just make a plug for people to send ideas or think hard about that.