En Garde, Online

BU Law faculty are confronting the internet’s most existential questions, including how to prevent harmful and illegal content while still protecting free speech rights.

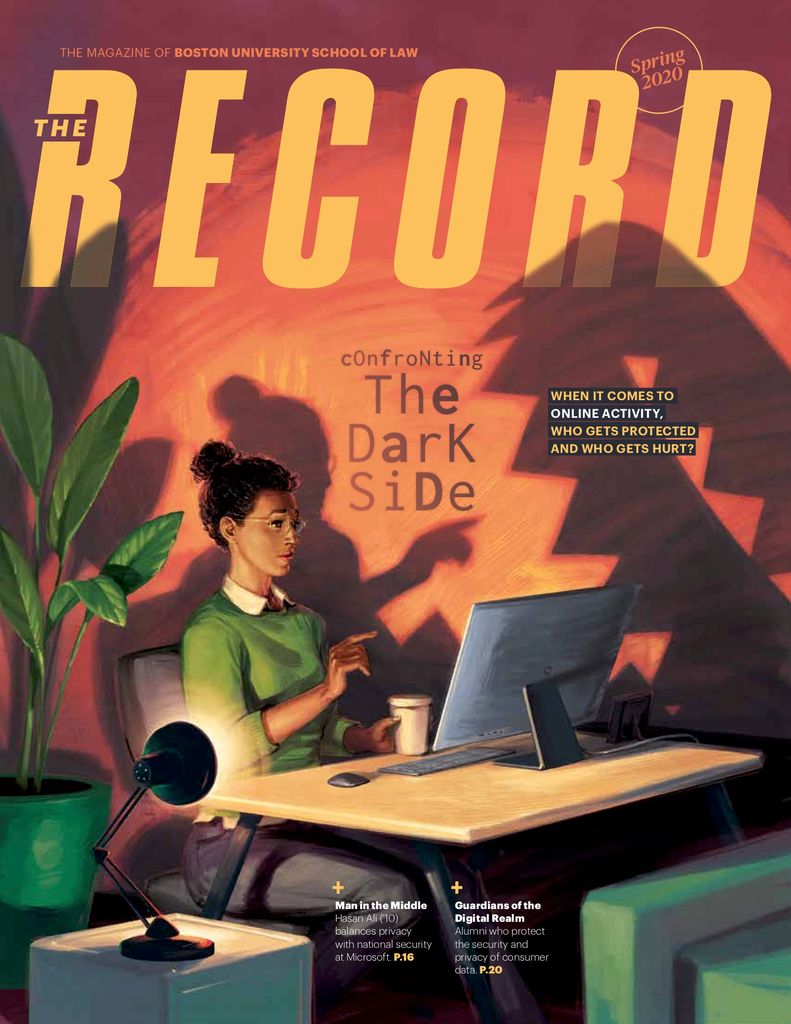

Illustration by Sam Hadley

En garde, Online

BU Law faculty are confronting the internet’s most existential questions, including how to prevent harmful and illegal content while still protecting free speech rights.

When Twitter Chief Executive Officer Jack Dorsey announced late last year that his social media platform would not publish political ads in an effort to curb the spread of misinformation, BU Law Professor Danielle Citron celebrated the decision.

“Bless Jack Dorsey,” she says.

Citron, acting as an unpaid consultant, advises several technology companies, including Twitter, about their online safety policies. She argues platforms have an obligation to remove or disclose the origins of ads that contain “manifest falsehoods.” But what she views as a step in the right direction for Twitter was offset by an opposite move from Facebook, another company she advises. Just a few days earlier, Facebook had refused to take down a Trump campaign ad that falsely claimed Democratic presidential candidate and former vice president Joe Biden had made aid to Ukraine contingent on the country dropping an investigation into a company connected to his son. Facebook Chief Executive Officer Mark Zuckerberg and other officials at the social media platform defended their decision on free speech grounds.

They were met with skepticism.

“Do you see a problem here with a complete lack of fact-checking on political advertisements?” Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (CAS’11) asked Zuckerberg in an October 23 hearing.

“I think lying is bad,” Zuckerberg said. “That’s different from it being, in our position, the right thing to do to prevent your constituents or people in an election from seeing that you had lied.”

Citron says she was “deeply disappointed” by Facebook’s decision.

“There are some categories of speech that have no protection,” she says. “Free speech only takes you so far.”

How far? In an era where much of our communication and social interaction has moved online—an environment replete with abuse ranging from revenge porn and cyberbullying to doctored videos and state-sponsored propaganda—that inquiry has become central to the work of policymakers, technology executives, law enforcement agencies, and everyday internet users. In the search for answers, BU Law experts like Citron are offering their guidance and expertise.

Finding solutions won’t be easy. Simultaneously preserving freedom of expression, personal privacy, and the integrity of basic democratic processes and institutions is tricky, says Clinical Instructor Andrew Sellars. Sellars directs the Technology Law Clinic, which represents BU and MIT students whose work might bump up against intellectual property, data privacy, civil liberties, or media and communications laws.

“Everything Zuckerberg said about censorship is only one-half of the equation,” he says. “It’s not speech for speech’s sake. The good consequences that flow from speech should be our higher focus. Our understanding of the world comes from discussion and pushback and disagreement.”

I think lying is bad. That’s different from it being, in our position, the right thing to do to prevent your constituents or people in an election from seeing that you had lied.

The Good, the Bad, and the In-Between

In 2018, Sellars jumped into a particularly thorny speech controversy with a Slate piece defending the right of Defense Distributed, a self-described “private defense contractor,” to disseminate plans for how to make a gun using a 3D printer. He argued the plans should be publicly available (a position gun control advocates abhorred) so regulators and law enforcement officials can better understand how to confront and control 3D-printed firearms (an argument Second Amendment advocates abhorred).

“I managed to irritate both sides of this debate,” Sellars says, laughing.

He acknowledges he might reconsider his position if the plans being disseminated were for large-scale explosives rather than a handgun capable of firing a single shot. Still, he felt strongly enough about the underlying issue to wade into the frothy waters of the First and Second Amendments.

“I worry greatly about a world in which we’re not allowed to discuss these sorts of things on the internet,” he says. “I want to make sure that we approach legislation around computer science and technology in a well-informed way, that the public understands how these things work so they understand how they can be regulated.”

Sellars says information such as the 3D-printed gun instructions can be thought of as “dual use” speech: capable of producing harm (in this case, a weapon that is difficult to detect) but containing “redeeming” social value as well (in this case, information allowing government officials to better understand how to prevent that harm).

Of course, the question of what is good or bad speech—and who gets to make that judgment—is complicated. But some speech is more obviously harmful than other kinds of speech. Citron focuses much of her attention on defamation, the nonconsensual sharing of nude images or videos (sometimes referred to as “revenge porn”), and so-called “deepfakes” (videos manipulated to show people saying things they never said or engaging in acts they never engaged in). A leading privacy expert, Citron joined the BU Law faculty in July 2019 and received a MacArthur “genius” grant in September 2019. She became interested in online harassment in the mid-2000s when several women law students were targeted—including with rape threats—by anonymous users of a law school forum called AutoAdmit.

“It just struck me at the time,” she recalls. “I understood all that as fundamentally a civil rights problem. Privacy invasions were being used to essentially disenfranchise women, many of whom were women of color, women from religious minorities, sexual minorities. That began my journey sort of thinking about these issues.”

Part of the difficulty in stemming harmful online speech, Citron and others argue, lies in a decades-old law that was originally designed to give internet developers the freedom to innovate without the threat of potentially devastating financial liability. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 grants immunity, with certain exceptions, to computer service providers for the content that appears on their platforms. In a 2017 article published in the Fordham Law Review, Citron and coauthor Benjamin Wittes argue Section 230 has been treated as a “sacred cow” and a “boon for free expression.” With extreme deference from judges, the law has been used to excuse, among other things, sites that post people’s nude images without their consent, online policies specifically designed to prevent the detection of sex trafficking, and a wide variety of statements proven to be defamatory.

Citron argues that letting platforms off the hook for their users’ harmful or illegal free expression has actually suppressed the free expression rights of another group: victims of online harassment.

“Speech can silence speech,” she says.

In 2014, Citron wrote Hate Crimes in Cyberspace, a book that features the stories of real women who suffered professional and financial harm as a result of the harassment they faced online. Brittan K. Heller, a Yale Law School student who aspired to work in human rights, was one of them. Her own job search was affected by the posts anonymous AutoAdmit users were making about her on the forum.

“At first, law firms were very eager to interview me,” she says. “Then, one of them asked me if I’d googled myself.”

Heller and another woman who was harassed on the site sued. Despite the attention garnered by their case—and court-ordered discovery that allowed them to unmask some of their harassers (many of whom were fellow law students)—they eventually agreed to a confidential settlement.

“I had gone out to determine whether an average person could get redress if something like this happened to them, and the answer was immediately no,” Heller says. “I didn’t want to create bad law” on appeal.

Still, the case—and Citron’s interest in it—led Heller to apply her passion for human rights to the technology world as the founding director of the Anti-Defamation League’s Center for Technology and Society.

Citron “was one of the first people to make the argument that by silencing one person’s ability to speak out, you’re actually having a negative net impact on freedom of expression,” Heller says. “She realizes that speech is not a zero-sum game.”

In Search of Reasonableness

In their article, Citron and Wittes propose what they call a “modest statutory change” that could help incentivize online platforms to do a better job policing harmful content on their sites: adding a clause to Section 230 that conditions immunity on “reasonable steps to prevent or address unlawful uses of [a provider’s] services.”

Professor Citron’s book Hate Crimes in Cyberspace (Harvard University Press, 2014) was named one of the “20 Best Moments for Women in 2014” by Cosmopolitan magazine.

Professor Citron’s book Hate Crimes in Cyberspace (Harvard University Press, 2014) was named one of the “20 Best Moments for Women in 2014” by Cosmopolitan magazine.That broad addition to the law’s language is designed to be flexible, Citron says, because, “of course, what’s reasonable depends on the kinds of problems you’re trying to solve.”

With such a standard, people who suffered harm because of someone’s online posts about them could sue online platforms and have a fighting chance in court.

“Instead of just having a free pass, a platform would have to show their speech policy,” Citron says. “They couldn’t hide it anymore. That keeps everyone on their toes vis-à-vis illegality.”

But litigating what’s reasonable would likely be an insurmountable burden for start-up internet companies like the kinds Sellars and his students sometimes represent.

“I worry about reasonableness—not on behalf of Google, Facebook, Twitter, and the other majors, but on behalf of the clients we see in our clinic,” Sellars says. “To litigate the question of reasonableness, they’d have to spend a lot of money to get to that answer.”

Still, under the status quo, Citron points out, “having no legal leverage over platforms is pretty costly to the victims” too. Part of the problem is that it’s almost impossible to hold actual harassers accountable. Because they often hide their hate behind anonymous user names, would-be plaintiffs are rarely able to identify whom to sue.

“They’re essentially judgment-proof” in civil cases, Citron says.

[Citron] was one of the first people to make the argument that by silencing one person’s ability to speak out, you’re actually having a negative net impact on freedom of expression. She realizes that speech is not a zero-sum game.

User Beware

In criminal cases or matters of national security, law enforcement agencies use a broad range of computational technologies to predict, prevent, and pursue bad actors, but Associate Professor Ahmed Ghappour argues there are risks to doing so. In a 2017 piece for the Stanford Law Review, Ghappour highlights the potential problems that can arise when governments use malware—or “network investigative techniques”—to remotely search computers on the dark web. Because most potential targets are outside the United States, he says, “any given target is likely to be located overseas.”

“It’s not that we shouldn’t hack,” he continues, “but the extraterritorial aspects of network investigative techniques demonstrate the need for new substantive and procedural regulations.”

Instead of letting “rank-and-file” personnel direct such decisions, which could have sovereignty or foreign relations implications, Ghappour argues executive agencies such as the Department of Justice, the State Department, and the National Security Agency should come together to develop policies that can preemptively guide online probes that might extend into other countries.

In a forthcoming research project titled “Machine Generated Culpability,” Ghappour considers the difficult questions that come with presenting technological evidence in court. For example, humans can’t possibly monitor the massive amounts of information posted online around the world, so social media platforms rely heavily on artificial intelligence to flag potentially illegal or harmful content. For Ghappour, that’s a concern as well, particularly in the criminal justice context.

He argues the nature of software-generated evidence makes it virtually impenetrable using conventional adversarial mechanisms, a lack of transparency that runs counter to the Constitution’s fair trial protections.

“The rules regulate a defendant’s power to participate by examining the evidence of their adversary, and by presenting competing evidence and argumentation in support of their case,” Ghappour says, “but machines cannot be cross-examined in their own right, and their vulnerabilities are typically undetectable without access to highly technical, highly sensitive information.”

The need for procedural checks could not be more urgent. Research shows that machines are as biased as their human makers and sometimes just don’t work like they should. In November 2019, the New York Times published an extensive article describing the unreliability of a technology depended on every day in courts across the country: breath tests designed to detect drunk drivers. And a state judge in Manhattan has ruled—on more than one occasion—that there is no scientific consensus to support the use of a particular DNA analytic tool. “This judge continues to conclude that we should not toss unresolved scientific debates into judges’ chambers, and especially not into the jury room,” the judge wrote in September.

Ghappour agrees.

“Existing safeguards have a long way to go if they are going to protect us from erroneous machine evidence,” he says. “That’s a huge, huge problem.”

Finding Common Ground, and Solutions

Solving such problems—or at least finding better ways to mitigate them—will require the collective brainpower and will of more than just lawyers and legal scholars. BU Law has a longstanding collaboration with the Hariri Institute for Computing and Computational Science & Engineering—the BU Cyber Security, Law & Society Alliance—in which law professors, computer science researchers, and social scientists engage on critical questions involving technology and ethics. (Ghappour, it should be noted, previously worked as a computer engineer: “I can legitimately say my job was to hack supercomputers,” he explains.)

“We have an exceptional number of people in both the law school and the computer science department who are interested in helping lawmakers make more informed policy in the technological space,” says Professor Stacey Dogan, associate dean for academic affairs.

Much of the work is complementary, and the scholars often build on each other’s ideas and understandings. Citron has written previously about “technological due process”—the ability to have notice of and challenge decisions made by nonhuman arbiters in administrative law settings; Ghappour is now exploring that concept in depth in the criminal context. Like Citron, Dogan studies online platform liability. But Dogan’s expertise is in the intellectual property realm where intermediaries do have a statutory obligation to remove harmful—or, in the case of intellectual property, infringing—content. The similarities and differences the two scholars have identified in their respective fields have them talking about how they can collaborate in the future.

“All of us are engaged in research that’s really trying to capture the benefits of technology while also limiting the risk of harm,” Dogan says.

The stakes are high. No one wants to stand in the way of innovation. But neither does anyone want to be left without recourse when a runaway technology ruins her life on- or offline. “We are in a moment of deep uncertainty,” Citron says. “When it comes to tech, we often adopt first and ask questions later. We have to take stock. We can’t just say, ‘We’re going to build it; deal with it.’ Maybe we don’t build it. That’s precisely why I came to BU. I want to be surrounded by people who are thinking about these things.”