The Road to 2030: What Role for Chinese Development Finance?

By Rebecca Ray

By 2030, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) other than China must mobilize an ambitious $3 trillion annually to meet their development needs and avoid the catastrophic impacts of climate change. Further complicating this challenge is the fact that development finance has slowed dramatically in the last few years. A new working paper by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center explores this challenge in depth, with a particular focus on the role of Chinese development finance institutions (DFIs).

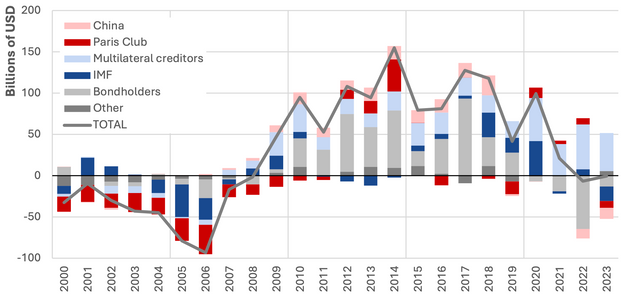

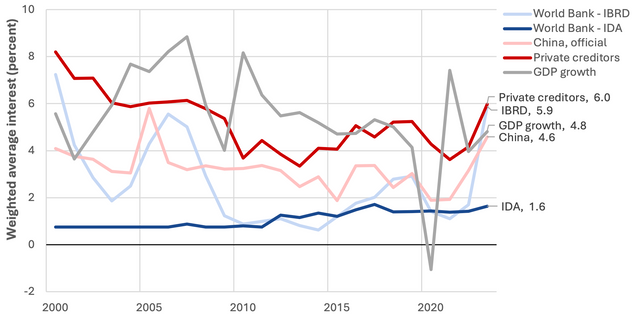

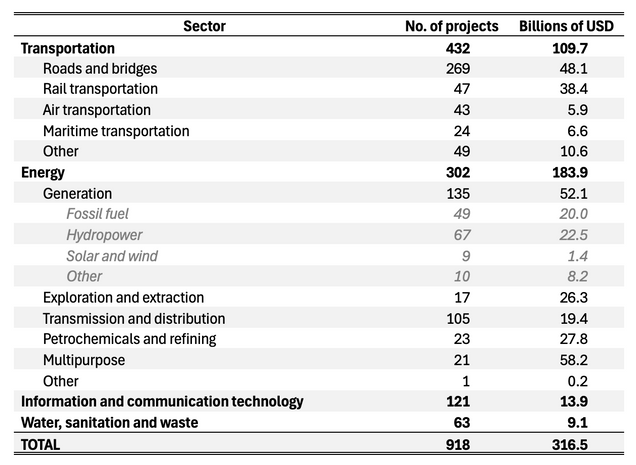

As Figure 1 shows, after 2020, LMICs have seen a sharp decline in net transfers––the difference between new disbursements coming in and the money going out to repay existing debts, including principal and interest payments. For low-income countries (LICs) in particular, net transfers have remained positive with two exceptions: Public and Publicly Guaranteed (PPG) debt net transfers from China and from bondholders.

Figure 1: Net PPG Debt Transfers by Creditor and Borrower Group

A. Net PPG Debt Transfers to All Low- and Middle-Income Countries Except China

B. Net PPG Debt Transfers to IDA-Eligible Countries

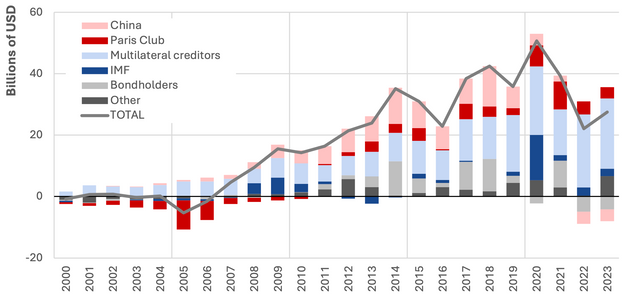

In part, this drop-off can be explained by China’s lending cycle: a rapid expansion in sovereign debt followed by a slowdown. Repayments have come due as new disbursements have fallen off. As Figure 2 shows, Chinese overseas development finance (ODF) surpassed new lending from the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in 2009 and again from 2015-2017, but has since fallen to below $10 billion per year.

Figure 2: Sovereign Financing Commitments by China (CDB, CHEXIM), World Bank and ADB, by USD billion, 2008-2024

The working paper gives an overview of economic benefits and risks from the surge in Chinese lending and subsequent negative net transfers. It offers policy recommendations for reviving lending in cases where it can be beneficial, while minimizing the economic risks of the recent negative net transfers.

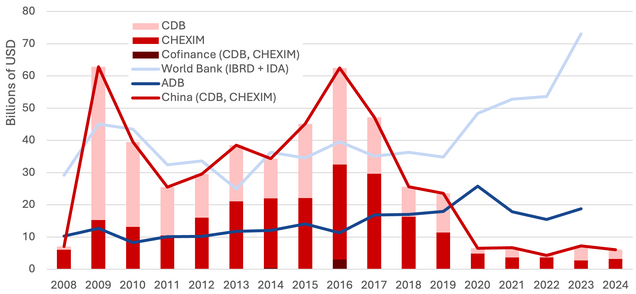

Chinese Development Finance in Comparison to Other Lenders

Economically, Chinese development finance differs from major multilateral development bank (MDB) lending in several key ways, including the cost of capital and its relationship with GDP growth. For most of the past two decades, the weighted average interest rate of Chinese official lending has been higher than that of the World Bank, although still below average economic growth rates in LMICs. Recently, however, this trend has begun to reverse as the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD)––the World Bank’s window for lending to middle-income countries (LICs) ––has seen rapidly rising interest rates.

Figure 3: Weighted Average Interest Rate of LMICs’ New PPG Debt, by Creditors, 2000-2023

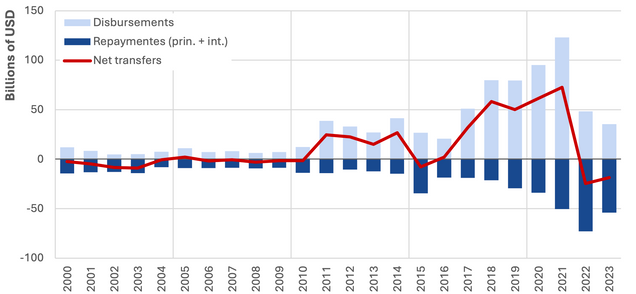

However, Chinese development finance is also more closely linked to economic growth in borrowing countries, according to a growing body of scholarly research. In part, this relationship reflects the higher importance of infrastructure and public assets in Chinese ODF than in MDB finance, allowing it to address economic bottlenecks and become more integrated in global value chains. Table 1 details the distribution of this Chinese infrastructure lending across sectors, with particular emphasis on transportation and energy projects.

Table 1. China-Financed Overseas Infrastructure Projects, 2008–2024

In addition to the public asset building shown in Table 1, however, it is also important to consider the impact on natural capital, the ecosystems and resources that underpin all economic activity and effectively act as another level of infrastructure. Recent research finds that Chinese ODF is negatively correlated with natural capital growth in borrowing countries and carries higher risks to biodiversity and Indigenous communities––who are disproportionately dependent on natural capital––than the World Bank lending. Thus, in the long term, it will be important for Chinese DFIs to bolster their environmental and social risk management so that the expansion of built infrastructure do not come at the expense of the natural systems that sustain them.

Chinese Recent Net Transfers in Comparison to Other Lenders

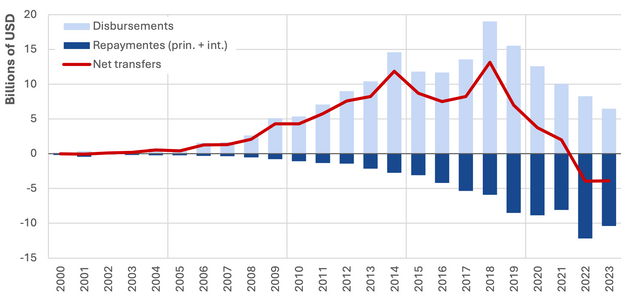

As Figure 1 shows above, Chinese net PPG lending transfers have shifted from positive to negative for low-income countries. Figure 4 breaks this down further for the group of low-income and high-vulnerability countries that are eligible for borrowing from the International Development Association (IDA)––the World Bank’s window for lending to low-income countries. China’s official disbursements peaked in 2017 and have been falling steadily since then, while repayments to China peaked more recently in 2022 and exceed new disbursements, leading to negative net transfers overall.

Figure 4: Disbursements, Interest and Principal Repayments and Resulting Net Transfers on PPG Lending from China to IDA-Eligible Countries, in Billions of USD, 2000-2023

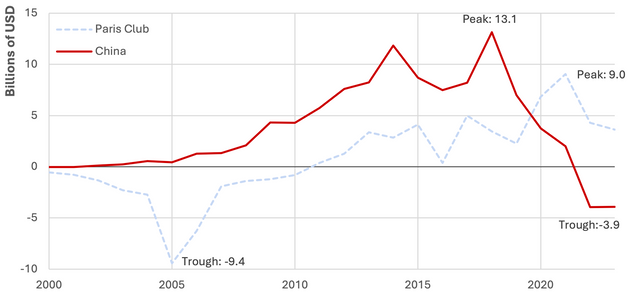

However, Figure 1 also shows that this transition from positive to negative net transfers is not unusual among lenders undergoing domestic economic volatility, as seen with Paris Club lenders in the mid-2000s. Figure 5 provides more detail for this comparison: while Chinese net transfers have reached a low of −$3.9 billion per year, Paris Club net transfers hit a much more severe trough in 2005, of −$9.4 billion. Thus, the negative net transfers from China are in line with historical patterns, echoing recent research indicating that net transfers are positively correlated with lenders’ domestic economic growth.

Figure 5: Net Transfers from China and Paris Club Lenders to IDA-Eligible Countries, 2000-2023

Indeed, China’s domestic economic prospects have been complicated from net negative transfers from its own international lenders, as Figure 6 shows. In other words, it’s now repaying more than it’s receiving. These inbound net transfers hit a low of −$24.7 billion in 2022 before rebounding to −$18.6 billion in 2023.

Figure 6: Net PPG Credit Transfers to China, 2000-2023

China’s Net Transfers Among IDA Borrowers

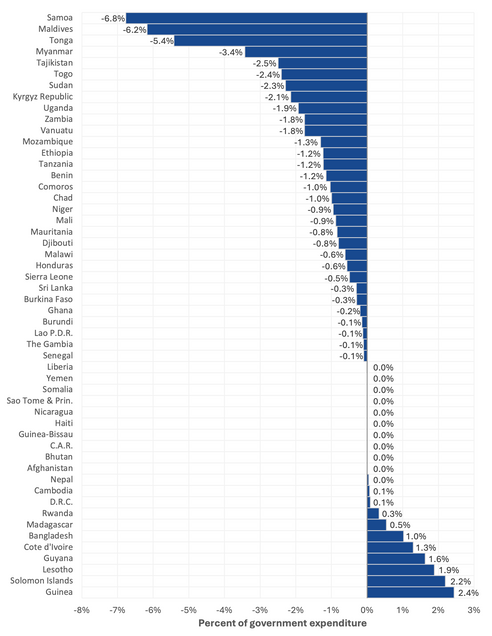

Geographically, China’s negative net transfers are relatively concentrated among a small group of borrowing countries. Figure 7 shows these net transfers as a share of government expenditures in 2003. In four countries––Samoa, the Maldives, Tonga and Myanmar––the net transfers were equivalent to over five percent of government spending in 2023. In another five countries––Tajikistan, Togo, Sudan, the Kyrgyz Republic and Uganda––they accounted for over two percent of government spending.

Figure 7: Net Transfers from China to IDA-Eligible Countries, 2023, % of Government Spending

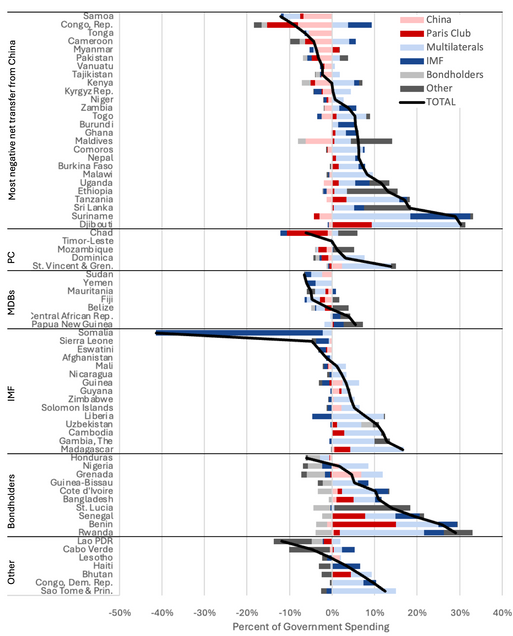

As with the overall net transfers to IDA countries, it is important to consider China’s net transfers to individual countries alongside other lenders. Figure 8 shows how each IDA country’ net transfers compare across all major creditor categories. Borrowers are classified by which lender had the most negative transfer to them: 26 countries had more negative net transfers from China than from any other creditor category, five saw the most negative net transfer from Paris Club lenders, seven from multilateral creditors, 15 from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), 10 from bondholders and seven from other creditors. The black line in Figure 8 shows each country’s total net transfers. For nine countries in the “China” section, including Samoa, Congo, Tonga, Cameroon, Myanmar, Pakistan, Vanuatu, Tajikistan and Kenya, the total net transfers were negative, meaning that they were not able to bring in enough new money from other lenders to compensate for negative net transfers from China.

Figure 8: Net PPG Transfers to IDA Countries, by Creditor Category and Total, 2023, % of Government Spending

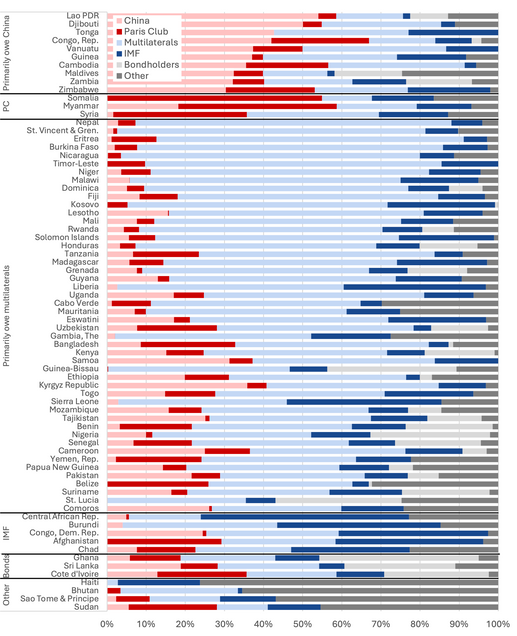

While these negative net transfers matter for the countries directly affected, it is worth remembering that, for most IDA countries, the largest share of their external PPG debt is owed to multilateral creditors, as Figure 9 shows. Indeed, 48 of the 73 countries shown in Figure 9 owe the largest share of their external PPG debt to multilateral creditors, followed in a distant second place by China (10 countries), the IMF (five countries), bondholders and Paris Club creditors (three countries each) and other creditors (four countries).

Figure 9: Share of External PPG Debt Stock, 2023, IDA-Eligible Countries

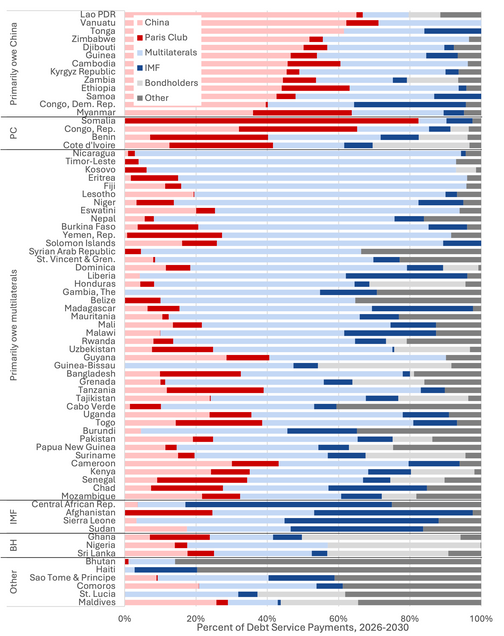

A similar distribution appears in Figure 10, which looks at debt service payments scheduled for 2026-2030. Again, most IDA countries (43 of 73) expect a plurality of their debt service payments to go to multilateral creditors over the next five years, followed at a great distance by China (13 countries), Paris Club creditors and the IMF (four countries each), and bondholders (three countries), with the remaining six countries expecting to predominantly repay other creditors.

Figure 10: Share of External PPG Debt Service, 2026-2030, IDA-Eligible Countries

Reviving Chinese Overseas Development Finance in the Global South

Over the last 20 years, China has played a crucial role in mobilizing development finance for public assets and economic growth. The challenge now is how to return to this beneficial role while minimizing economic risks for borrowing countries and itself? A five-pronged approach can mitigate near-term risks while meeting longer-term opportunities:

- Refinance existing debts in renminbi (RMB) at lower interest rates. China’s domestic interest rates have fallen below Western lenders’, providing a historic opportunity to refinance existing debt in China’s domestic currency.

- Exchange at-risk loans for longer-term, RMB-denominated bonds. Bonds can be traded, creating space on DFI balance sheets for future growth.

- Provide new, long-term lending for green growth to countries that do not need refinancing. This lending should be project-focused rather than discretionary, so that it does not simply repay other creditors such as bondholders.

- Engage in cooperative foreign direct investment (FDI) in countries with manufacturing capabilities, so that finance and investment work together toward industrial development.

- Expand RMB-denominated trade, ensuring an adequate flow of RMB to enable repayment of RMB-denominated debt.

*

Read the Working Paper 阅读中文博客